Com Para Tie Lapte Franta Brazil 2002

-

Upload

florin-nechita -

Category

Documents

-

view

215 -

download

0

Transcript of Com Para Tie Lapte Franta Brazil 2002

-

8/6/2019 Com Para Tie Lapte Franta Brazil 2002

1/15

Innovative strategies in the food processing industry: fundamental relationshipsbetween institutional, competitive, technological and organizational dimensions

(Case studies)*

Jean Philippe [email protected]

Antonio Domingos [email protected]

Luiz Carlos [email protected]

Orlando [email protected]

Centro de Estudos e Pesquisa em Agronegcios / Universidade Federal do Rio Grande doSul

Av. Joo Pessoa, 31 Sala 202Porto Alegre /Rio Grande do Sul - 90010-282

BrasilTelephone: (055) (51) 33163484 / Fax: (055) (51) 33163281

Vincent [email protected]

Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique Unit dEconomie et SociologieRurales de Grenoble

Universit Pierre Mends France BP 47 38040 Grenoble Cedex 9France

Telephone: 33 (0) 476825439 / Fax : 33 (0) 476825455

* The Fundao Coordenao de Aperfeioamento de Pessoal de Nvel Superior CAPES, supported this research.Their support is gratefully acknowledged. We would like to thank Oscar Alfranca for his helpful comments andcriticisms on previous drafts.

-

8/6/2019 Com Para Tie Lapte Franta Brazil 2002

2/15

ABSTRACT

This research use case studies as an approach to give evidence of the systemic relationsand the existent trade-offs between the institutional, competitive, technological andorganizational variables involved in the process of innovation in the food processing industry.

The unity of analysis consists of dairy processors that recently launched new products in the fluidmilk market. The results converged in showing the growing importance of non-price competitivestrategies and the concomitantly need to adequate a public policy to generate variety in thetechnological and organizational forms in order to foster industry competitiveness.

-

8/6/2019 Com Para Tie Lapte Franta Brazil 2002

3/15

INTRODUCTION

Continuous innovation is an issue of vital importance for the strategic management offood processing companies that wish to access or stay in quality based markets. In particular, thealignment of product differentiation and market segmentation represent a essential competitive

strategy to face the consequences of the changing balance power in the food retailer-foodprocessing industry relations and the rapid evolution of consumer behavior with respect toagricultural and food products. This research illustrates how progress along a technologicaltrajectory and the emergence of new ones results from the interplay between institutional,competitive, technological and organizational variables.

1. OBJECTIVES

The aim of this study is to evaluate the relationships between some fundamentalinstitutional, competitive, technological and organizational factors in the innovation processcarried out by food processing firms as defined a priori in the specific literature. The basicquestions are: i) How the innovation process is deployed? ii) Why the firms innovate? iii) Whatare the main determinants to develop innovation in this sector?

2. METHODOLOGY

We use case studies as an approach to give evidence of the systemic relations and theexistent trade-offs between those factors. We choose a research design with one unity of analysis(food processors that recently launched new products and explored new markets in the fluid milkproduction chain) and multiple case studies (two firms in Brazil and two in France whichlaunched some of the principal product innovations in this market during the 90s, respectively:Premium UHT milk, sterilized milk and organic UHT milk, microfiltrated milk). Clearly, thestructure and strategies developed by suppliers, the dairy industry and the retail food distributionsystem are undergoing rapid change in those countries helping to show the robustness of thephenomenon across different and complex contexts. The contrast in those two sectoral innovationsystems1 acted as a revelatory tool. In particular, the fluid milk market is a hard test to productinnovation considering its ordinary character2 and the domination of retail products3 - finally, thesupremacy of one process technology (Ultra High Temperature - UHT processing) limits thetechnological strategies diversity adopted by the food processors4. Afterwards, we compareenterprises with the same structural profile in the two countries: multinational enterprises MNE(very large multi-product/brand firms) and small and medium enterprises - SME. Thisconfiguration is specially useful and robust to confront the theoretical basis, where each case isselected by the researcher to confirm convergent or contrasting evidence between the cases5, 6.Data from the selected enterprises were collected in semi-structured interviews (Table 1) withprincipal decision-makers. Complementary, we interviewed independent specialists that closelyfollowed the innovation process. The context of the study and the search for conflictinginformation was obtained in technical journals, sector reports and academic work. Finally, theempirical observations are compared with similar and conflicting theory about innovation in thefood industry in the hope to generalize them to theoretical propositions and not to populations oruniverses5. The implications between the specific theory and the phenomenon are explicit in thediscussion of the results.

-

8/6/2019 Com Para Tie Lapte Franta Brazil 2002

4/15

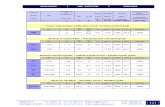

Table 1: Interview guide characterization of the sectoral system of innovation1

Innovation project features Origin and motivationSearched benefitsInternal agents mobilizedTeam organization

Mechanisms for product differentiationMechanisms for market segmentationMechanisms for trade marketing

Characteristics of theknowledge base (mobilizedto innovate)

Sources of innovation: internal R&D, entrepreneur, suppliers, users,concurrenceAccessibility of knowledgeTacit or codified characterLevel of specificity and complexity

Characteristics of thetechnological trajectories

Incremental or radical characterSpecificityCumulativity (at the firm, sector or cluster level)Irreversibility

Appropriability (patents, industrial secrets, pioneering, structuralbarriers to imitation)Accessed opportunitiesPerformance of technologiesConcurrent technologiesAccessed barriers of entryComplementary actives

Nature of learning processes,competencies, organizationand behavior of firms (toinnovate)

Comportamental diversityOrganizational learningAdoption of new methods and techniquesChanges in the strategic orientationLevel of technological dependence

Co-specialization effects between departmentsInternal coordinationVertical and horizontal inter-relations andcomplementarities

Level of complementary between internal and external R&DImpacts (due to innovation) in the production chainLevel of cooperation with universities, financial and researchinstitutions, governmental agenciesLevel of cooperation with technological suppliersCluster effectsCooperation mechanisms: joint-ventures, R&D agreements, licensing,direct investment, user-supplier relationshipsImportance of public politics: industrial, fiscal, monetary, commercialImportance of consumption patterns: emergence of new trends

-

8/6/2019 Com Para Tie Lapte Franta Brazil 2002

5/15

3. RESULTS

3.1 The institutional and competitive context of the innovative process

France Brazil

Retail participation inthe packaged foodsales

80 %7 82%8

Retail concentration In 2002 the 3 largest retail possessed 64% ofthe market9

In 2001 the 3 largest retailpossessed 42% of the market10

Incidence ofdistribution brands inthe fluid milk market

Over 60% Limited

Relative bargainingpower of retail

Strong and growing11, 12, 13 Strong and growing14

Structure of theequipment suppliersegment

In concentration National clusters in disintegration growing dependence oninternational suppliers15Monopolist position16, 17

Importance of publicresearch institutions toforster innovation

Very important (specially to SME)18 Limited8

Concentration in thedairy industry

High: 2,1% of the enterprises responds for55,6% of production19, 20; in 1995, 3 groups

processed more than 40% of totalproduction21

Growing concentration throughacquisitions of PME by MNE8,

15,22

Dominanttechnologicaltrajectory

UHT processing / PEAD and carton presentation

New possibletechnologicaltrajectory

Microfiltration - MF associated with light UHT / PEAD and cartonpresentation

Main strategies in thedairy sector - MNE

Product differentiation, extend product line,market segmentation11, 12

Intensive advertisement, productdifferentiation8, brandconsolidation, market

segmentation23

Main strategies in thedairy sector - SME

Focus on niche markets12 and pioneering11, 21 Focus on niche markets anddefensive strategies (imitation of

MNE)8, 15

Distribution channel selection4

Fluid milk production 3,9 billion liters in 2001

24

5,3 billion liters in 2001Evolution of fluid milkmarket

Regression (- 8% between 1989 to 1999)21 Growing (+50% between 94 to2000)

Fluid milk marketrelative to dairyproducts market(volume processed)

17% in 200124 50% in 19978

-

8/6/2019 Com Para Tie Lapte Franta Brazil 2002

6/15

Fluid milk markets (in2001)

Pasteurized milk: 3,0% (partlydifferentiated)

Sterilized milk: 7,1% (no differentiation)UHT milk: 89,9% (75% generic and 25%

modified)21, 24

Pasteurized milk: 27% (partlydifferentiated)

UHT milk: 73% (90% genericand 10% modified)4

3.2 The French case studies

Case A MNE Case B - SME

Characteristics ofthe new product

Organic UHT milk (4 months of shelflife without refrigeration) PEAD bottle

Microfiltrated milk (15 days of shelf lifea 4-6C) PEAD bottle

Innovation sources Raw milk suppliers Process equipment suppliers / ResearchInstitute

Motivation Try to segment ordinary UHT milkmarket / valuate products and brand

Process alternative to small scale dairies/ face UHT milk boost

Trigger event Crazy cow crisis (1996) Rapid market displacement of pasteurized milk by UHT milk

Strategies PioneeringRapid niche exploration

Positive impact in company image andbrand

Extend product lineTrade marketing

PioneeringNiche exploration

Positive impact in company image andbrand

Productdifferentiationsources

Health and well beingEthical concerns

Quality labeling:Agriculture Biologique

Taste profile (close to pasteurized milk)with extended shelf life; gastronomic

value, terroir appealFocused marketsand distributionchannels

NationalMainly big retail

Local, regional and national80% big retail20% groceries

Actual importanceof the product tothe company

Represents 3% of sales of the UHT lineMarginal impact in profitability

Represents 50% of total sales

Internal projectagents

Multidepartments Director and small team

Appropriability PioneeringConsolidated brand

Pioneering and idiosyncratic learning

External inter-relations

Focused in develop raw milk supply andlogistics due its geographic dispersion

Better commercial relations with retail,

but without specific cooperation

Process equipment suppliers, researchinstitute, marketing consulting, public

entities (sanitary control)

Retail: feed-backsabout consumeracceptanceLearning processes Supply management Product and process development

External relations managementInnovative culture

Governmentalsubsidies

Important to production segment Important to processing segment

Innovativeproducts impact in

Guaranteed shelf space in retailersstores even after the launch of identical

Guaranteed shelf space in retailersstores

-

8/6/2019 Com Para Tie Lapte Franta Brazil 2002

7/15

trade marketing products with retailers or processingfirms brands

Benefits for retails brand: complete lineof products associated with the offer of a

cheaper (- 20%) retail brand substituteBetter margins with new products

No direct concurrenceBenefits for retails brand: differentiate

from concurrenceBetter margins with new products

3.3 The Brazilian case studies

Case C - MNE Case D - SME

Characteristics ofthe new product

Premium UHT milk (4 months of shelflife without refrigeration) PEAD bottles

Sterilized milk (4 months of shelf lifewithout refrigeration) PEAD bottles

Innovation sources Process equipment suppliersRaw milk suppliers

Process equipment suppliers

Motivation Try to segment ordinary UHT milkmarket / valuate products and brand

Process alternative to small scale dairies/ face UHT milk boost

Trigger event Commoditization of ordinary UHTmilk

Valuate products and brand

Rapid market displacement ofpasteurized milk by UHT milk

Strategies PioneeringDifferentiation

Positive impact in company image andbrand

Extend product lineTrade marketing

PioneeringDifferentiation

Positive impact in company imageTrade marketing

Increase logistics flexibility (comparedto pasteurized milk)

Permits to explore seasonal effects inraw milk productions

Productdifferentiationsources

Natural appeal raw milk selectionFirst UHT milk in PEAD bottles

First long conservation milk in PEADbottles

Focused marketsand distributionchannels

Regional and national Regional

Actual importanceof the product tothe company

Represents 15% of sales of the UHT line Represents 30% of total sales

Internal projectagents

Multidepartments and inter-firms(international exchanges)

Director and small team

Appropriabilityaspects

PioneeringConsolidated brand

Intensive advertisement

Pioneering

External inter-relations

International process equipment suppliers International process equipmentsuppliers

Learning processes Product and process developmentExternal relations management

External relations management

Governmentalsubsidies

No No

Innovative Guaranteed shelf space in retailers stores Guaranteed shelf space in retailers

-

8/6/2019 Com Para Tie Lapte Franta Brazil 2002

8/15

products impact intrade marketing

No direct concurrenceBenefits for retails brand: differentiate

from concurrenceBetter margins with new products

storesNo direct concurrence

Benefits for retails brand: differentiatefrom concurrence

4. DISCUSSION

The opportunity conditions in the two countries are very different: even though the marketsize (fluid milk) is larger in Brazil, the level of direct and indirect subsidies and marketsophistication/diversification are greater in France. Nevertheless, in both countries, the level ofconcentration is growing concomitantly in the dairy sector and retail - both seeking brandconsolidation and market segmentation by the offer of innovative products what turns vertical(specially in France) and horizontal (in France and Brazil) competition a fiercely process (asectors characteristics, as evidenced by many authors37, 44, 45, 51). The technological opportunitiesexplored in the two countries are somewhat diverse: i) in Brazil the product innovations in fluidmilk still are predominantly incremental, concerning packaging and product formulationvariations; ii) in France, the emergence of a new technological trajectory27 in fluid milk

processing (microfiltration) may represent an important technological path. In both situationspowerful equipment suppliers orchestrate the sectoral evolution.

In all of the case studies clients and consumers are considered in relation to the emergingmarkets consequence of new needs, life-styles and socio-economic trends. Nevertheless, theinnovation strategies seems to be predominantly related to competitive positioning, speciallypioneering in new products/technologies (as evidenced by other authors30 for the European foodprocessors) what paradoxically can limit formalized research on consumers behavior or trademarketing impact. Here again, market intelligence prevails over market orientation as observed inother innovative food processors case studies28. As a matter of fact, market selection andtechnological paths co-evolve in a complex (and rather incremental) way27 what indicate thecomplementary role of marketing studies in forecasting the direction of the innovative

opportunities.Although the external technological offer, the knowledge base mobilized in the SME to

innovate depends in a preponderantly tacit process based in the entrepreneur competency toconsider the fit between the market opportunity, the technology specificitys and the firmcapabilities to explore them and forecast the possible evolution of this complex system.Otherwise, as process technology (like MF) needs to be adapted to raw material particularitiesand the need to coordinate and integrate internal and external actors gain importance (asdemonstrated for other SME in the food industry18, 29) the idiosyncratic character of the learningprocess became evident. In the case of the MNE, even considering the mature character of thetechnologies and the higher degree of formalization, the processes of selection and coordinationof external partners (raw milk suppliers, equipment suppliers, research institutes) and integration

between multidepartements call for tacit capabilities and leadership.All the case studies illustrate the dynamics of a sector which depends extensively on

public and private organisms suppliers of technology embedded in equipment, suppliers ofmaterials or components and an applied research network4, 30, 31, 32, 33 . Besides, the switch betweenthe search for external complementarities and the mobilization of internal capacities illustratesthe interactive innovation model with feedbacks where the R&D activities are instrumental34 - asobserved for other food processing firms28, 30, 32.

-

8/6/2019 Com Para Tie Lapte Franta Brazil 2002

9/15

The importance of the institutional structure is explicit in the French case studies.Considering the organic UHT milk production chain, the offer of subsidies and the consolidationof a normative structure were very important to incentive the conversion of many producers -amplifying the production base35 and to configure this production system26. The definition ofspecific norms applied to the organic production even if based in an obligation of results and

not of ways associated with the adoption of one, well recognized, label of quality permitted toassure the consumers and promote the rapid diffusion of the organic products25. Paradoxically,this institutional apparatus didnt favor the production segment since the over production of rawmilk lead to a lost in its value - even if the production of organic milk present many tacit andcomplex learning features. In this case, these effective appropriability mechanisms (to the rawmilk producers) where annulled as a competitive advantage due the lack of a geographicdelimitation in the production (like in the Appelation dOrigine Controle production systems).The standardization of the key elements in a quality food production process can diminish thepotentiality of the differentiation strategies36.

In a similar way, in the adoption of the MF technology by the SME, the existence of apublic research unit (whose director represents a technological gate keeper) favored theestablishment of key inter-relations between the specific actors concerned (equipment supplier,research institute, SME internal team and public organisms responsible to food control) and thetechnology adaptation (the importance of public institutions to the innovation process have beenillustrated in the French food processing SME18, 32).

In Brazil, the impacts due to the institutional structure in the innovation process were of amuch smaller dimension. The principal relation between the research institutions and the dairiesis related to product or process quality control8. Otherwise, the one-way profile in the relationsbetween equipment suppliers and fluid milk processors limits the development of innovativetechnologies and products4, 8. These features characterize a system of innovation excessivelydependable on international technological suppliers8 which raises the costs and limits theadequability of the technological options15, limits the technological variety4 and restraints co-evolution between the agents with lost in competitiveness specially to the SME8, 15.

One convergent feature in the cases is related to the low appropriability of thetechnologies developed and offered by equipment suppliers - specially, in the case of SME. Evenif the knowledge base associated with the technology adaptation present some elementsindicating a tacit and complex learning, the effectiveness of marketing complementary strategies(advertising, distribution channel selection, brand positioning) which can potentially enhancethe benefits in pioneering - are limited by the modest financial and technical resources of SME(as noted for other SME in the food processing sector37). Besides, the growing need to serve thebig retail restrain the opportunities to explore new markets since the bigger dairy processors with complete lines in each product category and a great capacity to promote them keep anasymmetric bargaining power and dominate the shelf spaces (as observed in the dairy sector inFrance11 and in the food processing segment in general44, 46, 48).

Nevertheless, the success of SME in first exploring market niches indicates a greaterflexibility and acuity in the perception of new consumer needs38. In this sense, it is critical to theSME the capacity to profit the first stages of the technological cycle, process dependable on itsagility in the mobilization of internal resources in order to detect emerging niche markets andselect and adapt new technologies32, 39. Indeed, the greater technological variety and the diversityof strategic choices, characteristic of the early stages in the life cycle of one sector as in the pre-paradigmatic stage of a new technology when a dominant design have not consolidated yet40

favors the SME41. Eventhough, it is a problematic situation to visualize surviving only in this

-

8/6/2019 Com Para Tie Lapte Franta Brazil 2002

10/15

period of ferment: the potential for the optimization of organizational processes, to reacheconomies of scale and to permit reliable and stable relations with suppliers is limited since thefirst technological discontinuities rarely became an industry standard - a dominant design onlyconsolidate as an evolution of the original breakthrough42. This dynamic feature seems to beconfirmed in the evolution of the MF technology: the first technological configuration (1,4 m

MF membranes 15 days of shelf life at 4-6C) - adopted by the SME focused in the case study -is about to be menaced by a more developed system (0,5 m MF membranes associated withlight UHT - 4-6 months of shelf life at ambient temperature) the latter technological option ismore adapted to the larger dairy processors.

In a much more comfortable position, the MNE can establish entry barriers to smallerconcurrence - by selecting technologies that demands high financial commitments and benefitfrom scale economies - and surviving constraints since the performance evolution of thedominant design tend to be incremental and routinized - stimulating concentration27, 41. Thisdynamic is especially true considering that the development of close and technically creativesupplier relationships appear to be keys to successful, continuing dominance of the biggerenterprises and that the equipment suppliers who head the technological development may putenough weight behind a particular design to make it a standard42:616. Besides, following Suttonspropositions43, endogenous sunk costs can deter competition from SME too as growing marketingand P&D fixed costs require a higher level of sales to amortize them44, 45, 46. Indeed, productinnovation in the food industry will be better explored if the adoptants have the necessaryadvertising capacity (as in the case of Premium UHT milk), brand positioning (as in the case ofthe organic UHT milk) and technological leadership (as in the new MF variant) permitting thebigger firms to explore scope economies and shelf space in retail.

Even considering these asymmetries, there is convergence in all cases studies consideringthe critical effects in pioneering the development of new technologies and in the offer of newproducts (as emphasized by other authors44): it guaranteed shelf space in retailers stores, evenafter the launch of identical products with retailers brands. Complementary, the usual exigenciesof retail related to marketing support47 seemed to be softened (as was the case with sterilizedmilk). Besides, innovation was an important tool to generate brand loyalty and reputation andfunctioned as a partial substitute to advertisement since notoriety came along with novelty (as inthe case of the MF milk). The importance of increasing the frequency of new productslaunches19, 48, 49 and market segmentation46, 50 seem to be clear to all the enterprises focused in thecase studies. Nevertheless, the retail capacity to rapid respond with similar products and ownbrands was especially important in France19, 21, 51, 52.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The results converged in showing the growing importance of non-price competitivestrategies in a context of accruing concentration in the processing and distribution segments. Inthis context it is very important to deploy an adequate public policy to generate variety in thetechnological and organizational forms in order to foster industry competitiveness. In this sense itwould be critical to maintain an effective network capable to sustain a process of continuousinnovation in the SME of the food industry - as their survival will depend on the exploration ofever-shorter periods in the beginning of technological cycles. This aim seems to be critical inBrazil considering the fragility of the institutional structure to support innovation in this industry.The establishment of cooperation mechanisms between public research institutes, food processingmachinery industry, regularization and control organisms were more relevant to the innovative

-

8/6/2019 Com Para Tie Lapte Franta Brazil 2002

11/15

French processing firms than the Brazilian ones. Nevertheless, in some situations thespecifications of food quality standards and production regulations had ambiguous effects: in oneway they limited opportunism in the chain and helped to communicate the differentialcharacteristics of the food products to consumers, in the other way they limited theappropriability of the innovations. The research illustrates how progress along a technological

trajectory and the emergence of new ones results from the interplay between institutional,competitive, technological and organizational variables.

REFERENCES

1. Breschi, S. and F. Malerba, 1997. Sectoral innovation systems: technological regimes,Schumpeterian dynamics, and spatial boundaries. Pp.130-156 in C. Edquist, ed., Systems ofinnovation Technologies, Institutions and Organizations. London and Washington: Pinter.

2. Siebert, J. W., R. Schwart, M. Pritchard and M. Seidenberger, 2000. Suiza foods corporation:

best management strategy in the fluid milk industry. International Food and AgribusinessManagement Review, 3: 445-455.

3. Galizzi, G., L. Venturini, and S. Boccaletti, 1997. Vertical relationships and dual brandingstrategies in the Italian food industry. Agribusiness, 13(2): 185-195.

4. Rvillion, J. P., A. D. Padula and A. Brandelli, 2001. Estudo das variveis relevantes naadoo da tecnologia de processamento UHT nas agroindstrias de laticnios no estado do RioGrande do Sul. Revista do Instituto de Laticnios Cndido Tostes, 323(56): 3-12.

5. Yin, R. K. 1994. Case study research: design and methods. 2 nd edition. London: SagePublications.

6. Sterns, J. A., D. B. Schweikhardt and H. C. Peterson, 1998. Using case studies as an approachfor conducting agribusiness research. International Food and Agribusiness Review, 1(3): 311-327.

7. Carrier, C., A. Edy and W. El Singab, 2002. Le panorama du systme alimentaire en Europe.Pp. 11-35 in S. Miloszyk, J. Achehaifi, Y. El Maslouhi and J. L. Rastoin, eds., Marchs, Filireset Systmes Agroalimentaires en Europe. Montpellier: Institut Agronomique Mditerranen deMontpellier.

8. Bortoleto, E. 2000. Trajetria e demandas tecnolgicas nas cadeias agroalimentares do

MERCOSUL ampliado - Lcteos. Montevideo: PROCISUR/BID.

9. GMS Dossier Spcial Grandes et Moyennes Surfaces: ce quil faut savoir, inwww.fdsea51.fr/actualites/communiques.

10. ABRAS Associao Brasileira de Supermercados - Ranking 2001 in www.abrasnet.com.br

-

8/6/2019 Com Para Tie Lapte Franta Brazil 2002

12/15

11. DHauteville, F., G. Bardou and J. M. Codron, 1996. LInnovation Produit dans la RelationFournisseur Distribuiteur en Agro-Alimentaire. Programme Aliment 2000 Innovation, ProjetGIPIA N R 93/13. Montpellier: Chaire de Gestion-GRAAL, ENSA.

12. Richard, E. and B. Sylvander, 1997. La filire lait biologique: stratgies dacteurs,dveloppement de march - Rapport n97-03P. Le Mans: INRA-ESR.

13. Drescher, K. and O. Maurer, 1999. Competitiveness in the european dairy industries.Agribusiness, 15(2): 163-177.

14. Farina, E. M. M. Q. 2001. Challenges for Brazils food industry in the context ofglobalization and Mercosur consolidation. International Food and Agribusiness ManagementReview, 2(3/4): 315-330.

15. Dirven, M. 2001. Dairy clusters in Latin America in the context of globalization.International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 2(3/4): 301-313.

16. Santos, C. F. M. 1999. Novas tecnologias e o selo verde. Revista Leite & Derivados, 8(44):30-43.

17. Massote Primo, W. 1999. Restries ao desenvolvimento da indstria brasileira delaticnios. Pp. 71-127 in D. Vilela, M. Bressan and A. S. Cunha, eds., Restries Tcnicas,Econmicas e Institucionais ao Desenvolvimento da Cadeia Produtiva do Leite no Brasil.Braslia: MCT/CNPq/PADCT, Juiz de Fora: EMBRAPA CNPGL.

18. Le Bars, A. 2001. Innovation sans recherche: les comptences pour innover dans les PME delagro-alimentaire. These de Doctorat en Economie Applique. Grenoble: Universit PierreMends-France UFR Dveloppement Gestion Economique et Socits.

19. Trail, B. 1997. Structural changes in the European food industry: consequences forinnovation. Pp. 38-60 in B. Trail and K. G. Grunert, eds., Product and Process Innovation in theFood Industry, Suffolk: Chapman & Hall.

20. Trail, B. and J. Gilpin, 1998. Changes in size distribution of EU food and drinkmanufacturers: 1980 to 1992. Agribusiness, 14(4): 321-329.

21. Imelda, H., R. Elisabeth and E. M. Youns, 2002. La filire lait. Pp. 57-75 in S. Miloszyk,J. Achehaifi, Y. El Maslouhi and J. L. Rastoin, eds., Marchs, Filires et SystmesAgroalimentaires en Europe. Montpellier: Institut Agronomique Mditerranen de Montpellier.

22. Jank, M. S., M. F. Paes Leme, A. M. Nassar and P. Faveret Filho, 2001. Concentration andinternalization of Brazilian agribusiness exporters. International Food and AgribusinessManagement Review, 2(3/4): 359-374.

23. Reardon, T. and E. Farina, 2002. The rise of private food quality and safety standards:illustrations from Brazil. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 4: 413-421.

-

8/6/2019 Com Para Tie Lapte Franta Brazil 2002

13/15

24. CNIEL Centre National Interprofessionnel de lEconomie Laitire. 2002. LEconomieLaitire en Chiffres. Paris: Le Clavier.

25. Sylvander, B., F. Porin and P. Mainsant, 1998. Les facteurs de succs de qualit spcifiquesdans lagro-alimentaire. Rodez: VII Journes des Sciences du Muscle et Technologies de laViande.

26. Sylvander, B. 2000. Les tendances de la consommation des produits biologiques en Europe.Pp. 192-212 in G. Allard, C. David and G. Henning (eds.). Lagriculture biologique face sondveloppement les enjeux futurs. Lyon: Editions INRA.

27. Dosi, G. 1982. Technological paradigms and technological trajectories. Research Policy,11: 147-162.

28. Grunert, K. G., H. Harmsen, M. Meulenberg and B. Trail, 1997. Innovation in the foodsector: a revised framework. Pp. 213-226 in B. Trail and K. G. Grunert, eds., Product andProcess Innovation in the Food Industry, Suffolk: Chapman & Hall.

29. Mangematin, V. 1997. De la capacit d'absorption la capacit de gestion : l'exemple desP.M.I. de l'agro-alimentaire en Rhne-Alpes. Cahiers dEconomie et Sociologie Rurale, 44: 85-105.

30. Christensen, J. L., R. Rama and N. G. Von Tunzelmann, 1996. Innovation in the europeanfood products and beverage industry. Industry studies of innovation using C.I.S. data. Bruxelles:European Commission EIMS Project 94/111 EIMS Publication n35.

31. Martinez, M. G. and J. Burns, 1999. Sources of technological development in the spanishfood and drink industry. A supplier-dominated industry ? Agribusiness, 15(4): 431-448.

32. Mangematin, V. and N. Mandran, 1999. Do non-R&D intensive industries benefit ofspillovers from public research? The case of the Agro-food industry" in A. Kleinknecht, P.Monhen and E. Elgar, eds., Innovation and Economic Change: Exploring CIS micro data.

33. Trail, B. and M. Meulenberg, 2002. Innovation in the food industry. Agribusiness, 18(1): 1-21.

34. Kline, S. J. and N. Rosenberg, 1986. An overview of innovation. Pp. 275-305 in R. Landauand N. Rosenberg, eds., The positive Sum Strategy. Washington: National Academy Press.

35. ONILAIT Office National Interprofessionnel du Lait et des Produits Laitiers. Enqute sur la

filire laitire biologique en 2001 Premiers rsultats. Mai 2002.

36. Khl, R. W. 1997. Quality labelling. Pp.127-136 in F. Nicolas, L. Lagrange and G. Giraud,coords., conomie et Marketing Alimentaires Actes du colloque des 20 et 21 juin 1997, ENITAde Clermont-Ferrand, Paris: ditions Tec & Doc.

37. Grunert, K. G., H. Harmsen, M. Meulenberg, E. Kuiper, T. Ottowitz, F. Declerk, B. Trail andG. Goransson, 1997. A framework for analysing innovation in the food sector. Pp. 1-33 in B.

-

8/6/2019 Com Para Tie Lapte Franta Brazil 2002

14/15

Trail and K. G. Grunert, eds., Product and Process Innovation in the Food Industry, Suffolk:Chapman & Hall.

38. Noteboom, B. 1994. Innovation and diffusion in small firms: theory and evidence. SmallBusiness economics, 6: 327-347.

39. Audretsch, D. B. 1995. Innovation, growth and survival. International Journal of IndustrialOrganization, 13: 441-457.

40. Abernathy, W. J. and J. M. Utterback, 1978. Patterns of industrial innovation. TechnologyReview, 80: 41-47.

41. Utterback, J. M. and F. F. Surez, 1993. Innovation, competition, and industry structure.Research Policy, 22: 1-21.

42. Anderson, P. and M. L. Tushmam, 1990. Technological discontinuities and dominantdesigns: a cyclical model of technological change. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(4):

604-633.

43. Sutton, J. 1991. Sunk Costs and Market Structure: Price Competition, Advertising, and theEvolution of Concentration. Cambridge: MIT Press.

44. Galizzi, G. and L. Venturini, 1996. Product innovation in the food industry: nature,characteristics and determinants. Pp. 133-153 in G. Galizzi and L. Venturini, eds., Economics ofinnovation: the case of food industry. Heidelberg: Physica Verlag.

45. Venturini, L. 1997. Vertical competion and forms of cooperation. Pp.23-35 in F. Nicolas,L. Lagrange and G. Giraud, coords., conomie et Marketing Alimentaires Actes du colloquedes 20 et 21 juin 1997, ENITA de Clermont-Ferrand, Paris: ditions Tec & Doc.

46. Connor, J. M. and W. A. Schiek, 1997. Food Processing An Industrial Power House inTransition. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

47. Park, J. L. 2001. Supermarket product selection uncovered: manufacturer promotions andthe channel intermediary. International Food and Agribusiness Management Review, 4: 119-131.

48. Connor, J. M. 1981. Food product proliferation: a market structure analysis. AmericanJournal of Agricultural Economics, 63(4): 607-617.

49. Cotterill, R. W. 1997. The food distribution system of the future: convergence towards theUS or UK model ? Agribusiness, 13(2): 123-135.

50. Steenkamp, J-B, E. M. 1997. Dynamics in consumer behavior with respect to agriculturaland food products. Pp. 143-188 in B. Wierenga, A. Van Tilburg, K. Grunert, J-B. E. M.Steenkamp and M. Wedel, eds., Agricultural Marketing and Consumer Behavior in a ChangingWorld. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

-

8/6/2019 Com Para Tie Lapte Franta Brazil 2002

15/15

51. Hugues, D. 1996. Building partnerships and alliances in the european food industry Pp.101-117 in G. Galizzi and L. Venturini, eds., Economics of innovation: the case of food industry.Heidelberg: Physica Verlag.

52. Hugues, A. 1997. The changing organization of new product development for retailersprivate labels: a UK US comparison. Agribusiness, 13(2): 169-184.