JDRE4

Transcript of JDRE4

ACADEMIA DE STUDII ECONOMICE DIN BUCUREŞTI

THE BUCHAREST ACADEMY OF ECONOMIC STUDIES

Jurnalul Cercetării Doctorale în Ştiinţe Economice

Journal of Doctoral Research in Economics

Vol. I nr. 4/2009

Bucureşti

2009

Jurnalul Cercetării Doctorale în Ştiinţe Economice 2

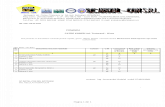

Cuprins

JDRE în ecuaţia sprijinului activităţii de cercetare doctorală .................................... 3

Laura Elena MARINAŞ

1. Cadru conceptual privind raportarea de sustenabilitate ....................................... 5

Elena-Roxana ANGHEL (ILCU)

2. Justiţia interacţională: legătura dintre reţinerea angajaţilor

şi acţiunile în justiţie în domeniul relaţiilor de muncă ........................................... 15

Raluca CRUCERU 3. Elemente noi privind reproiectarea sistemelor manageriale

în contextul trecerii la economia bazată pe cunoştinţe .......................................... 24

Ana-Maria GRIGORE

4. Propuneri de cuantificare a eficienţei raportării actorilor economici

la cerinţele politicii comunitare în domeniul concurenţei ...................................... 31

Nela Ramona ICHIM

5. Între marcă şi brand ................................................................................................. 39

Mihai PASTIREA

6. Principalele instrumente de marketing online utilizate

în vederea gestionării relaţiilor cu clienţii ............................................................... 51 Carmen PANTEA

7. Evenimentele de marketing sau marketingul evenimentelor ................................ 67 Marius Cătălin RUSESCU

8. Realitatea economică: riscuri sau şanse?

Perspectiva instituţiilor financiare internaţionale .................................................. 75 Erika SYTOJANOV

9. Eficienţa instituţiilor publice şi eficacitatea funcţionarilor publici ..................... 84

Nicoleta VĂRUICU Dan SĂNDULESCU

10. Schimbări de paradigmă ale modelului economic european

în contextul actualei crize mondiale ........................................................................ 88

Remus Marian AVRAM 11. ERM, o nouă abordare a procesului de management al riscurilor ...................... 102

Petronella NEACŞU 12. Lupta împotriva criminalităţii economice la nivel european prin acţiunea

asupra mobilului infracţiunilor: banii. Crearea unei reţele europene

între oficiile de recuperare a creanţelor ................................................................ 108

Cristian ANGHEL

Journal of Doctoral Research in Economics 2

Contents

1. Sustainability reporting framework ....................................................................... 3

Elena-Roxana ANGHEL (ILCU)

2. Interactional justice: the link between employee retention

and employment lawsuits ........................................................................................ 13

Raluca CRUCERU

3. New elements regarding managerial reengineering

in the knowledge-based economy ........................................................................... 22

Ana-Maria GRIGORE

4. Proposals of measuring the effiency of the economic agents reference

to the european competition policy ........................................................................ 29

Nela Ramona ICHIM

5. Mark versus brand .................................................................................................. 36

Mihai PASTIEA

6. The main online marketing tools used in managing customer relationships ..... 47

Carmen PANTEA

7. Events marketing or marketing the events............................................................ 63

Marius Cătălin RUSESCU

8. Economic downturn or rising opportunities?

The perspective of international financial institutions ......................................... 70

Erika SYTOJANOV

9. The efficiency of public institutions and effectiveness of public servants ........... 79

Nicoleta VĂRUICU

Dan SĂNDULESCU

10. Paradigm changes of european economic pattern

within present world slump .................................................................................... 83

Remus Marian AVRAM

11. ERM, a new approach to risk management .......................................................... 97

Petronella NEACŞU

12. Fighting economic crime at the European level by acting against its purpose:

money. Setting up a European network between asset recovery offices ........... 102

Cristian ANGHEL

Vol. I nr. 4/2009 3

JDRE

ÎN ECUAŢIA SPRIJINULUI ACTIVITĂŢII

DE CERCETARE DOCTORALĂ

JDRE este editat sub amprenta simbolicului număr 4. Din punct de vedere editorial,

se poate vorbi de parcurgerea unui mic ciclu. Cele patru numere de până acum

împrumută din maturitatea unui an cu patru anotimpuri, dar păstrează în acelaşi

timp perspectiva firească a aşteptărilor unui viitor mai bun, perfectibil în măsura

resurselor implicate şi a motivaţiei angajate. Experienţa editorială de până acum s-a

dovedit favorabilă calităţii şi consistenţei articolelor publicate.

Activitatea de cercetare şi publicarea rezultatelor ar trebui abordate într-o manieră

paradigmatică. Încă de la apariţia ei, o paradigmă este limitată în acoperirea

problemelor la a căror soluţionare se aşteaptă să aibă contribuţii majore. Există prin

urmare rezerve consistente cu privire la acceptarea unei paradigme, şi atunci, de ce

totuşi comunitatea ştiinţifică răsplăteşte aproape întotdeauna cu un aviz favorabil?

O paradigmă nu oferă soluţii imuabile, ci doar rezolvă probleme deja existente într-

o măsură mai bună decât celelalte teorii existente de până în acel moment. Întocmai

după acest model, activitatea de cercetare a doctoranzilor trebuie să se sprijine pe

încurajarea dezvoltării ideilor. În acest punct de referinţă al activităţii de cercetare,

contează mai puţin dacă o idee este genială sau mediocră, fiind mai importante

forţele şi resursele intelectuale angajate de către doctoranzi şi conducătorii lor

ştiinţifici.

La fel cu o paradigmă dintr-o ştiinţă naturală sau socială, cercetarea doctorală

răspunde la o serie de probleme fundamentale. Singura diferenţă este doar de

concept, în sensul că paradigmele definesc statutul şi limitele unei ştiinţe la un

moment istoric dat răspunzând la provocarea problemelor fundamentale ale

omenirii, iar cercetarea doctorală răspunde la cele mai importante probleme

ridicate cu privire la viitoarele teze de doctorat: caracterul de ştiinţificitate,

contribuţia personală, impactul temei studiate asupra mediului socio-economic sau

politic.

JDRE este dovedit a fi încă o dată un pilon important în definitivarea pregătirii

doctorale. Ştiinţa nu răspunde niciodată complet la problemele existente, şi nici

simpla existenţă a JDRE nu este o condiţie suficientă pentru susţinerea cu succes a

tezei de doctorat. Dar chiar dacă, la fel ca ştiinţa pe care o sprijină, JDRE nu

răspunde la toate problemele ridicate, reuşeşte totuşi să răspundă mai bine celor

care intră în jurisdicţia sa, iar acest lucru a fost deja în mod clar evidenţiat pe

parcursul numerelor anterioare.

Jurnalul Cercetării Doctorale în Ştiinţe Economice 4

Activitatea de cercetare doctorală prin intermediul JDRE este o componentă a

normalităţii ştiinţifice. Acest lucru poate să însemne că normal înseamnă ca ştiinţa

să răspundă unei probleme fundamentale prin ceva extraordinar, sau să ajute la

inventarea unui lucru inedit, care să schimbe modul de gândire al oamenilor într-o

nouă definire a normalităţii. Sau poate să însemne pur şi simplu o acreditare a

principiului lui Francis Bacon, conform căruia „Adevărul apare mai uşor din eroare

decât din confuzie”.

Lect. univ. dr. Laura Elena Marinaş,

Redactor-şef JDRE

Vol. I nr. 4/2009 5

CADRU CONCEPTUAL PRIVIND

RAPORTAREA DE SUSTENABILITATE

Elena-Roxana Anghel (Ilcu) Academia de Studii Economice din Bucureşti, România

Rezumat

Sustenabilitatea reprezintă o problemă importantă a secolului al XXI-lea întrucât implică

aspecte cheie referitoare la dezvoltarea economică, socială şi de mediu. Dezvoltarea

sustenabilă presupune un proces de utilizare eficientă a resurselor prin care se tinde către

satisfacerea nevoilor umane avându-se în vedere conservarea mediului astfel încât aceste

nevoi să poată fi satisfăcute nu numai în prezent, dar şi în viitor. Acest articol pune în

evidenţă schimbările de reglementare care au conturat raportarea de sustenabilitate,

începând cu apariţia noţiunii de dezvoltare sustenabilă, şi până în prezent. La finele

acestui studiu, întrebarea care se pune este: „Cum reacţionează companiile în condiţii de

raportare sustenabilă?”

Cuvinte-cheie: sustenabilitate, dezvoltare sustenabilă, cadru conceptual privind

raportarea de sustenabilitate, raportare de sustenabilitate

Clasificare JEL: M41, M48, M49

Introducere

Acest articol pune în evidenţă schimbările de reglementare care au conturat

raportarea de sustenabilitate, începând cu apariţia noţiunii de dezvoltare sustenabilă

şi până în prezent.

Una dintre cel mai des citate definiţii ale dezvoltării sustenabile este cea propusă de

Comisia Mondială a Mediului şi Dezvoltării (World Commission on Environment

and Development – WCED), condusă de către Gro Harlem Brundtland, prim-

ministru al Norvegiei în 1987. În conformitate cu Raportul Brundtland – „Viitorul

nostru comun” (Brundtland Report – „Our common future”), dezvoltarea

sustenabilă presupune „asigurarea unei dezvoltări care să permită satisfacerea

nevoilor generaţiilor prezente, fără a se compromite abilitatea generaţiilor viitoare

de a-şi satisface propriile nevoi”. Comisia a fost înfiinţată pentru a se adresa

preocupării generale de la nivel internaţional privind „deteriorarea accelerată a

mediului uman şi a resurselor naturale, precum şi consecinţele acestei deteriorări

asupra dezvoltării economice şi sociale”. Organizaţia Naţiunilor Unite (ONU)

acordă recunoaşterea acestei comisii în 1983 întrucât este conştientizat faptul că

problemele privind mediul înconjurător sunt globale, fiind astfel necesare politici

globale de dezvoltare sustenabilă.

Jurnalul Cercetării Doctorale în Ştiinţe Economice 6

Dezvoltarea sustenabilă reprezintă modalitatea prin care ţările aflate în curs de

dezvoltare şi aflate în plin proces de industrializare vor evita să devină precum

naţiunile industrializate din prezent bazate pe emisii intense de carbon.

Cei trei piloni ai dezvoltării sustenabile sunt: dezvoltarea economică, socială şi de

mediu, structuri ce se intercorelează reciproc şi la intersecţia cărora se află

conceptul de sustenabilitate.

Figura 1 Cei trei piloni ai dezvoltării sustenabile

(Sursa: Adams, W.M., 2006: 2)

Dezvoltarea sustenabilă – o istorie de reglementări

Ideea de sustenabilitate a apărut cu peste 40 de ani în urmă, în programul adoptat

de către Uniunea Mondială a Conservării (The World Conservation Union –

IUCN) în 1969.

A fost unul dintre punctele cheie de discuţie la Conferinţa Naţiunilor Unite privind

Mediul Uman (United Nations Conference on the Human Environment) de la

Stockholm, în 1972. Conceptul a fost dezvoltat astfel încât să exprime clar că este

posibilă dezvoltarea economică şi industrializarea statelor fără a fi afectat mediul

înconjurător.

În perioadele următoare, curentul de gândire privind dezvoltarea sustenabilă a fost

ameliorat progresiv prin Stratiegia Mondială de Conservare (The World

Conservation Strategy), 1980, formulată de către IUCN; totodată, prin Raportul

Brundtland pentru ca apoi acest curent să fie împrumutat în strategiile guvernelor

naţionale şi în organizaţiile de afaceri.

Iniţiativa de Raportare Globală (Global Reporting Initiative – GRI) este organizaţia

pionier în dezvoltarea Cadrului conceptual privind raportarea de sustenabilitate,

organizaţia fiind orientată, în perspectivă, pe rafinarea şi îmbunătăţirea continuă a

conceptelor. GRI a fost fondată în 1997 şi este formată dintr-o reţea ce cuprinde

mai multe mii de experţi din întreaga lume, stakeholderi care participă la grupurile

de lucru şi care aplică Cadrul conceptual de raportare sustenabilă, accesează

Vol. I nr. 4/2009 7

informaţiile ce au la bază Cadrul conceptual sau care contribuie la dezvoltarea

Cadrului conceptual sub alte modalităţi formale şi/sau informale.

Grupul de Lucru Interguvernamental de Experţi în Standardele Internaţionale de

Contabilitate şi Raportare (Intergovernmental Working Group of Experts on

International Standards of Accounting and Reporting – ISAR) a fost înfiinţat în

1982 şi lucrează sub patronajul Conferinţei Naţiunilor Unite de Comerţ şi

Dezvoltare (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development – UNCTAD).

Misiunea ISAR este aceea de a asista ţările în curs de dezvoltare şi economiile

aflate în tranziţie în implementarea celor mai bune practici de transparenţă şi

contabilitate în companii pentru a facilitata fluxul de investiţii şi dezvoltarea

economică. ISAR duce la îndeplinire această misiune printr-un proces integrat de

cercetare, consens interguvernamental, diseminare de informaţii şi cooperare

tehnică. Totodată, ariile de lucru ISAR sunt: implementarea IFRS, raportarea

privind guvernanţa corporativă, raportarea privind responsabilitatea corporativă şi

raportarea de mediu.

Raportarea de sustenabilitate în conformitate cu gri

Raportarea de sustenabilitate este o practică de măsurare şi transparenţă orientată

către grupurile de stakeholderi interni şi externi organizaţiei care tinde către

obţinerea performanţei în condiţii de dezvoltare sustenabilă. Un raport de

sustenabilitate trebuie să fie o reprezentare echilibrată şi credibilă a performanţei

sustenabile, incluzând atât contribuţiile pozitive cât şi cele negative ale

organizaţiei.

Rapoartele de sustenabilitate ce au la bază Cadrul conceptual de raportare

sustenabilă emis de către GRI pun în evidenţă ieşirile şi rezultatele companiei în

perioada raportată avându-se în vedere angajamentul organizaţiei, strategia acesteia

şi abordarea sa managerială.

Rapoartele de sustenabilitate pot fi utilizate având următoarele obiective:

Normalizare şi stabilire a performanţei de sustenabilitate în raport cu legile,

normele, codurile, standardele de performanţă, precum şi a iniţiativelor de

voluntariat;

Demonstrare privind modul cum organizaţia influenţează şi este influenţată de

către aştepările privind dezvoltarea sustenabilă;

Compararea performanţei între mai multe organizaţii şi evaluarea internă a

acesteia.

Toate normele ce compun Cadrul conceptual de raportare sustenabilă emis de GRI

sunt dezvoltate în baza unui proces care tinde să stabilească un consens prin dialog

între diferitele categorii de stakeholderi din mediul de afaceri, comunitatea de

investitori, protecţia muncii, societatea civilă, contabilitate, universitate precum şi

alte categorii. Fiecare normă este testată şi supusă unui proces continuu de

revizuire.

Jurnalul Cercetării Doctorale în Ştiinţe Economice 8

Normele de raportare emise de către GRI cuprind:

Cadrul conceptual de raportare;

Ghidul privind raportarea de sustenabilitate care este format din Principii şi

ghiduri, alături de Raportarea standard;

Protocoale privind raportarea de sustenabilitate;

Raportarea sectorială.

Figura 2 Cadrul conceptual de raportare sustenabilă emis de GRI

(Sursa: Ghid de raportare sustenabilă, 2006:3)

Cadrul conceptual de raportare

Este destinat pentru a fi utilizat ca un cadru de raportare general acceptat pentru o

organizaţie privind performanţa sa economică, socială şi de mediu. Poate fi utilizat

de către orice societate, indiferent de mărime, sector sau locaţie. Acesta ia în

considerare un ansamblu larg de aspecte cu care organizaţiile s-au confruntat în

timp şi în spaţiu. Totodată, acesta cuprinde norme aplicabile în activitatea

organizaţiilor la nivel general, cât şi la nivel specific generat de anumite sectoare

de activitate, norme ce sunt general acceptate de către o categorie largă de

stakeholderi din întreaga lume cu privire la raportarea de sustenabilitate a

organizaţiilor.

Ghidul privind raportarea de sustenabilitate

Cuprinde Principii şi ghiduri care stabilesc conţinutul raportului de sustenabilitate

pentru o organizaţie asigurând, totodată, calitatea acestuia. Totodată, acest ghid

cuprinde Raportarea standard care are în conţinutul său Indicatorii de performanţă

de sustenabilitate precum şi alte elemente tehnice de raportare.

Vol. I nr. 4/2009 9

Protocoale privind raportarea de sustenabilitate

Protocoale indicator existente pentru fiecare dintre Indicatorii de performanţă

cuprinşi în Ghidul privind raportarea de sustenabilitate. Prin aceste protocoale se

stabilesc definiţiile, metodologiile de calcul, precum şi alte informaţii utile pentru a

se asigura o analiză şi o interpretare consistente în ceea ce priveşte indicatorii de

performanţă sus-menţionaţi;

Protocoale tehnice sunt create cu scopul de a oferi îndrumare în alte aspecte ale

raportării, cum ar fi de exemplu limita nivelului de raportare. Sunt folosite alături

de Ghidul privind raportarea de sustenabilitate pentru a rezolva probleme cu care se

confruntă cele mai multe organizaţii în procesul de raportare.

Raportarea sectorială

Aspectele specifice pentru fiecare sector în parte sunt complementare Ghidului

privind raportarea de sustenabilitate, în sensul că, acestea arată cum se aplică acest

ghid într-un anumit sector de activitate şi cum se analizează indicatorii de

performanţă specifici pentru un astfel de sector.

Ghidul privind raportarea de sustenabilitate cuprinde următoarele elemente,

elemente considerate egale ca importanţă în întocmirea rapoartelor de

sustenabilitate:

Principii şi ghid de raportare;

Raportare standard (ce cuprind Indicatorii de performanţă).

Principiile şi ghidul de raportare

Această secţiune acoperă problematica conţinutului ce trebuie raportat de către o

organizaţie, cu respectarea următoarelor principii:

Principiul materialităţii;

Principiul importanţei stakeholderilor;

Principiul contextului de sustenabilitate;

Principiul completitudinii.

Principiile mai sus menţionate trebuie aplicate alături de următoarele principii care

asigură calitatea informaţiei raportate:

Principiul echilibrului;

Principiul comparabilităţii;

Principiul acurateţii;

Principiul istoric;

Principiul credibilităţii;

Principiul clarităţii.

Raportarea standard

În această secţiune este identificată informaţia relevantă şi materială pentru

majoritatea organizaţiilor, informaţie care este de interes pentru majoritatea

Jurnalul Cercetării Doctorale în Ştiinţe Economice 10

stakeholderilor, şi care cuprinde: strategia şi profilul organizaţiei, abordarea de

management precum şi indicatorii de performanţă ai acesteia.

Aceste principii au ca obiectiv transparenţa privind organizaţia ce raportează –

obiectiv asupra căruia sunt orientate toate aspectele ce sunt subscrise raportării de

sustenabilitate. Conform Ghidului de raportare sustenabilă emis de către GRI,

transparenţa poate fi definită ca fiind „raportarea completă a informaţiei cu privire

la aspectele şi indicatorii care reflectă impactul organizaţiei astfel încât să permită

stakeholderilor luarea de decizii, precum şi toate procesele, procedurile şi

estimările făcute în procesul de raportare”.

Pentru fiecare dintre principiile enunţate mai sus, a fost elaborată o definiţie, o

explicaţie şi o serie de teste care să permită şi să ghideze utilizarea acestora.

Figura 3 Principiile de raportare sustenabilă emise de către GRI

Principiul materialităţii – informaţia raportată trebuie să acopere toate

aspectele şi indicatorii care reflectă impactul organizaţiei din punct de vedere

economic, social şi de mediu, informaţie care este semnificativă pentru

categoriile de stakeholderi;

Principiul importanţei stakeholderilor – organizaţia trebuie să identifice

toate categoriile de stakeholderi care sunt afectate şi interesate, şi totodată, să

explice modalitatea prin care cerinţele acestora au fost satisfăcute;

Principiul contextului de sustenabilitate – organizaţia trebuie să arate

performanţa obţinută în contextul larg al sustenabilităţii;

Vol. I nr. 4/2009 11

Principiul completitudinii – organizaţia atinge aspectele, indicatorii de

performanţă şi limitele de raportare astfel încât acestea să fie suficiente pentru

reflectarea impactului semnificativ din punct de vedere economic, social şi de

mediu al organizaţiei şi totodată, să permită stakeholderilor să poată evalua

corect organizaţia din aceste puncte de vedere;

Principiul echilibrului – raportul de sustenabilitate trebuie să evidenţieze atât

aspectele negative cât şi cele pozitive ale performanţei organizaţiei din punct

de vedere sustenabil;

Principiul comparabilităţii – informaţiile trebuie selecţionate, analizate şi

raportate astfel încât să permită stakeholderilor comparaţii atât în timp cât şi în

spaţiu;

Principiul acurateţii – informaţia raportată trebuie să fie corectă şi suficient

de detaliată astfel încât stakeholderii să poată aprecia performanţa organizaţiei;

Principiul istoric – procesul de raportare trebuie să urmeze o anumită

frecvenţă în timp, la intervale orare regulate astfel încât informaţia să parvină

stakeholderilor în timp util;

Principiul clarităţii – informaţia trebuie să fie făcută publică pentru

stakeholderi într-o manieră ce o face uşor de înţeles şi aplicabilă;

Principiul credibilităţii – informaţiile şi procesele utilizate pentru întocmirea

raportului trebuie culese, înregistrate, calculate, analizate şi făcute publice într-

o manieră care permite testarea acestora şi care permite, totodată, stabilirea

nivelului de calitate al raportului de sustenabilitate.

Contabilitatea sustenabilă (de mediu)

În aceste condiţii se dezvoltă o nouă formă de contabilitate care formulează o

critică asupra practicilor existente, oferind practici contabile alternative. În acest

caz se pot formula un număr de întrebări: „Care este obiectivul contabilităţii

sustenabile (de mediu)?”, „Cum se urmăresc aceste obiective?”

În încercarea de a găsi un răspuns, se poate considera că, în particular,

contabilitatea sustenabilă (de mediu) este văzută ca un produs normativ al

universitarilor într-un context social dat. Pentru a se ajunge la anumite concluzii

este necesar un demers prin care să se reliefeze poziţia şi relaţiile care se stabilesc

între următoarele domenii: cercetarea în contabilitate, practica de contabilitate şi

funcţia educaţională de contabilitate.

Critica privind contabilitatea sustenabilă (de mediu) derivă din mai multe puncte de

vedere: critica din perspectivă Marxistă (Puxty, 1986), dintr-o perspectivă

feministă (Cooper, 1992), existând şi o perspectivă „intensiv verde” (Maunders şi

Burritt, 1991). Fiecare dintre aceste perspective oferă o imagine prin care se poate

judeca potenţialul contabilităţii sustenabile (de mediu). În aceste condiţii, Puxty

consideră că raportarea sustenabilă nu este decât o „nonschimbare de putere, având

în vedere că permite vechilor structuri să rămână neschimbate, ducând chiar la o

legitimare a acestora”. Sub perspectiva feministă, Cooper consideră că „aplicarea

Jurnalul Cercetării Doctorale în Ştiinţe Economice 12

contabilităţii sustenabile, deşi o idee bună în gândire, nu poate avea un rol hotărâtor

în actuala criză privind mediul”. Într-o manieră similară, Maunders şi Burritt, dintr-

o perspectivă „intens verde” consideră că „abordarea luminii verzi [contabilitatea

sustenabilă (de mediu)] este iremediabil contaminată de ideologia veche”.

Totuşi, chiar dacă prin perspectivă critică a fost pusă la îndoială capacitatea

contabilităţii sustenabile (de mediu) de a rezolva criza actuală cu privire la mediul

înconjurător, organizaţia GRI asigură o paletă de indicatori eonomici ce măsoară

performanţa sustenabilă a organizaţiei din punct de vedere economic.

GRI împarte aceşti indicatori în următoarele categorii şi subcategorii:

Performanţa economică;

Valoare economică generată direct şi distribuită, incluzând veniturile, costurile

operaţionale, compensările privind salariaţii, donaţiile şi alte investiţii în

comunitate, câştiguri reţinute şi plăţi pentru posesorii de capital şi pentru

guvern;

Implicarea financiară şi alte riscuri şi oportunităţi privind activităţile

organizaţiei datorită schimbării mediului de afaceri;

Planul privind beneficiile datorate ce urmează a fi acordate;

Asistenţa financiară semnificativă primită de la guvern.

Prezenţa pe piaţă;

Indicatori de tip rată ce pun în evidenţă şi compară salariul minim reglementat

şi salariul acordat în centrele de activitate;

Politici, practici, rate de proporţie a cheltuielilor pe baza furnizorilor

semnificativi la nivel local;

Proceduri pentru angajarea în câmpul muncii de personal al comunităţii locale,

precum şi ponderea acestor tipi de manageri.

Impactul economic indirect;

Dezvoltarea şi impactul asupra infrastructurii de investiţii, precum şi serviciile

furnizate în beneficiul comunităţii prin activităţile comerciale;

Înţelegerea şi punerea în evidenţă a impactului indirect semnificativ din punct

de vedere economic, considerându-se şi intensitatea acestuia.

Nivelul de asigurare privind rapoartele de sustenabilitate

Fiecare organizaţie care raportează sustenabil având la bază Cadrul conceptual

privind raportarea de sustenabilitate emis de către GRI trebuie să realizeze un

proces de autoevaluare al raportului de sustenabilitate întocmit. Organizaţia poate

alege să facă publice informaţii pe trei nivele de raportare, nivele evidenţiate în

Cadrul conceptual şi codificate C, B, şi A. Fiecare nivel cuprinde anumite

informaţii despre organizaţia ce face raportarea. În măsura în care raportul este

verificat de terţe părţi, calificativul nivelului atins primeşte semnul „plus” („+”),

luând astfel una dintre formele: C+, B+, A+.

Totodată, organizaţia trebuie să anunţe GRI de întocmirea raportului de

sustenabilitate punând la dispoziţia acesteia o copie a acestui raport.

Vol. I nr. 4/2009 13

Sustenabilitatea în România

Dezvoltarea sustenabilă în România se conturează imatur pe fundalul unui mediu

economic incert şi problematic. Avem de a face cu un concept importat, adus de

către marile corporaţii străine în lupta lor către extindere pentru pieţe şi clienţi noi.

Primii germeni care au dus la materializarea conceptului de dezvoltare sustenabilă

au apărut în SUA atunci când proprietarii de capital au intuit un comportament etic

în afaceri prin actul de filantropie corporatistă sau caritate corporatistă. Acesta

exprima gestul aceluia care deţine capitalul de a împărţi o parte din veniturile sale

cu alte categorii sociale. Din acest comportament derivă, ceea ce numim astăzi,

responsabilitate socială corporatistă. Iar responsabilitatea socială corporatistă,

alături de grija continuă pentru protejarea mediului înconjurător, duc implicit la

dezvoltarea sustenabilă propusă.

Dar companiile acţionează într-un mediu reglementat din punct de vedere politic.

În România, legile şi normele care privesc asistenţa şi protecţia socială sunt

instabile, şi în continuă schimbare. Totodată, salariul minim pe economie atinge

unul dintre cele mai mici niveluri din Europa.

Iar protejarea mediului înconjurător în România este luată în considerare atunci

când interesul o cere. Atunci când interesul are o natură monetară, mediul cade pe

planul doi. Un exemplu elocvent în acest caz este zăcământul aurifer de la Roşia

Montana. Pe de o parte, compania Roşia Montana Gold Corporation (deţinută în

proporţie de 80% de Gabriel Resources Ltd., o firmă canadiană) susţine că

zăcământul nu poate fi extras decât pe baza utilizării cianurilor, iar pe de altă parte,

avem în vedere efectul negativ şi de durată pe care acestea le au asupra mediului

înconjurător. În România, extracţia aurului cu ajutorul cianurilor este permisă prin

lege. Şi totuşi, există ţări, precum Cehia, Grecia etc., unde acelaşi lucru este

interzis prin lege (Diaconu, 2007). În asemenea caz, se naşte o dispută

problematică ce are în vedere comportamentul etic impus fie prin coduri interne de

etică, fie prin lege.

Însă dorinţa României de a se alinia standardelor Uniunii Europene, al cărei

membru este, va impune într-un final şi o aliniere a acesteia la practicile Uniunii cu

privire la asigurarea socială şi protejarea mediului înconjurător, şi nu numai.

Concluzii

În prezent, raportarea de sustenabilitate este un domeniu relativ nou şi o provocare

atât pentru normalizatori, în fundamentarea de norme, reguli, procedee, cât şi

pentru practicienii ce urmează a înţelege şi aplica aceste metodologii. Totuşi,

normalizarea privind raportarea de sustenabilitate are o acoperire cuprinzătoare atât

din punct de vedere teoretic cât şi practic dacă luăm în considerare faptul că

organismul de normalizare (GRI) este format din mai multe categorii de

stakeholderi, categorii ce reprezintă atât perspectiva teoretică cât şi perspectiva

practică. Un alt element extrem de important este faptul că normele emise se află

într-un proces continuu de revizuire.

Jurnalul Cercetării Doctorale în Ştiinţe Economice 14

Acestea fiind ştiute şi în ciuda perspectivei critice privind abordarea sustenabilă a

contabilităţii, noi considerăm că raportarea de sustenabilitate acoperă într-un grad

ridicat problematica de sustenabilitate oferind o imagine corectă a

comportamentului şi a impactului organizaţiei din punct de vedere al dezvoltării

durabile.

Problema care se naşte în aceste condiţii derivă din necesitatea auditării rapoartelor

de sustenabilitate generate de organizaţii, ştiut fiind faptul că în prezent nu există o

metodologie obiectivă şi standardizată privind verificarea autenticităţii

informaţiilor publicate în rapoartele de sustenabilitate. La această problemă,

organizaţiile răspund prin întocmirea acestor rapoarte în conformitate cu Cadrul

conceptual emis de către GRI, în conformitate cu politicile proprii privind

sustenabilitatea şi în conformitate cu alte reglementări emise de către alte

organisme (exemplu, Declaraţia Naţiunilor Unite privind Drepturile Omului).

Bibliografie

Adams, W.M. (2006), „The Future of Sustainability: Re-thinking Environment and

Development in the Twenty-first Century”, Report of the IUCN Renowned

Thinkers Meeting, 29-31 Ianuarie 2006;

Bebbington, J. (1997) Engagement, education and sustainability. A review essay

on environmental accounting, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability

Journal, Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 365;

Cooper, C. (1992), "The non and nom of accounting for (M)other Nature",

Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 5 No. 3, pp. 16-39;

Diaconu, B. (2007), „Între Roşia Montana şi Piatra Albă: Managementul răului

necesar”, Revista 22, Nr. 24 (891), 12-18 Iunie, disponibil la http://www.csr-

romania.ro/resurse-csr/analize-si-articole/intre-rosia-montana-si-piatra-alba-

managementul-raului-necesar.html

Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), Sustainability Reporting Guidelines, Version

3.0, (2006);

Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), Indicators Protocols Set: EC, Version 3.0, (2006);

Maunders, K.T. and Burritt, R.L. (1991), "Accounting and ecological crisis",

Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 4 No. 3, pp. 9-26;

Puxty, A.G. (1986), "Social accounting as immanent legitimation: a critique of a

technicist ideology", Advances in Public Interest Accounting, Vol. 1, pp. 95-

111;

United Nations (1983) "Process of preparation of the Environmental Perspective

to the Year 2000 and Beyond." General Assembly Resolution 38/161, 19

December 1983. Retrieved: 2007-04-11;

United Nations (1987) "Report of the World Commission on Environment and

Development." General Assembly Resolution 42/187, 11 December 1987.

Retrieved: 2007-04-12.

Vol. I nr. 4/2009 15

JUSTIŢIA INTERACŢIONALĂ:

LEGĂTURA DINTRE REŢINEREA ANGAJAŢILOR

ŞI ACŢIUNILE ÎN JUSTIŢIE

ÎN DOMENIUL RELAŢIILOR DE MUNCĂ

Raluca Cruceru Academia de Studii Economice din Bucureşti, România

Rezumat

Justiţia organizaţională este una dintre cele mai puţin înţelese şi utilizate unelte pentru a

crea medii de lucru mai bune şi mai eficiente.

În acest articol ne vom concentra pe conceptul de justiţie interacţională, vom analiza

impactul său şi vom oferi soluţii pentru un climat care va ajuta angajatorii să culeagă

recompensele şi să reducă riscurile legate de capitalul lor uman.

Există trei forme de justiţie organizaţională, cunoscute ca şi: justiţie ditributivă,

procedurală şi interacţională.

Justiţia distributivă se referă la ultima linie de front a conceptului de justiţie, adică: a fost,

până la urmă, corect rezultatul unei decizii? Această evaluare a corectitudinii implică, în

general, o comparaţie între ceea ce experimentează un angajat şi ceea ce se întâmplă

altora în aceeaşi organizaţie.

Justiţia interacţională este privită foarte personal. Ea se referă la comportamentul liderilor

organizaţiei, cum îşi duc la îndeplinire deciziile, în mod concret, cum îi tratează pe cei care

sunt subiectul deciziilor, acţiunilor şi, nu în ultimul rând, al autorităţii lor.

Justiţia interacţională este un element cheie în asumarea angajamentelor organizaţionale

şi în motivarea angajaţilor şi reţinerea acestora.

Organizaţiile ce creează un cadru pentru justiţia organizaţională vor culege roadele

capitalului uman în: motivare îmbunătăţită, o mai bună retenţie a personalului şi mai

puţine acţiuni în justiţie bazate pe relaţiile de muncă. Din păcate, organizaţiile care nu vor

face acest lucru s-ar putea să şchiopăteze, în timp ce competiţia sprintează spre înainte.

Cuvinte-cheie: justiţie organizaţională, justiţie interacţională, angajator, angajat,

leadership, proces

Clasificare JEL: A12, J53, K41

Introducere

Justiţia interacţională este un concept care a fost abordat şi a cărui explicare a

fost încercată atât de către sociologi cât şi de către psihologi începând cu secolul al

XIX-lea. Primul care a încercat să studieze comportamentul uman la lucru utilizând

o abordare sistematică a fost Frederick Winslow Taylor (1856-1915). Taylor a

studiat caracteristicile umane, mediul social, sarcinile, mediul fizic, capacitatea,

Jurnalul Cercetării Doctorale în Ştiinţe Economice 16

viteza, durabilitatea, costul şi interacţiunea unora cu celelalte. Obiectivul său

general era sa reducă şi/sau să elimine variabilitatea umană. Taylor a depus eforturi

mari pentru a-şi atinge scopul, acela de a face comportamentele umane predictibile,

în aşa fel încât maximum de randament să poată fi obţinut. El s-a bazat foarte mult

pe sistemele monetare stimulative, crezând cu tărie că oamenii sunt în primul rând

motivaţi de bani. A trebuit să facă faţă unor critici dure, inclusiv să fie acuzat că îi

sfătuieşte pe manageri să îşi trateze muncitorii ca maşini fără minte, dar munca sa

s-a dovedit a fi foarte productivă şi astfel a reuşit să pună bazele principiilor pentru

studiul managementului modern. Alţii, ca: Elton Mayo, Mary Parker Follett,

Douglas McGregor au încercat să găsească şi ei explicaţii pentru acel “ceva” care

făcea unele afaceri să meargă mai bine decât altele, dar credem că cea mai precisă

definiţie a Justiţiei Interacţionale, conceptul care revoluţionează modul în care

sunt privite relaţiile cu angajaţii şi productivitatea generată de aceastea, a fost dată

de John R. Schermerhorn ca fiind “… gradul în care oamenii afectaţi de o decizie

sunt trataţi cu demnitate şi respect”. (John R. Schermerhorn, et al., 8th ed., 2003,

Organizational behavior). Teoria sa se centrează pe tratamentul interpersonal pe

care îl primesc angajaţii atunci când sunt implementate proceduri.

Viziunea actuală asupra justiţiei interacţionale este că ea constă în două tipuri

specifice de tratament interpersonal.

Primul tip, etichetat ca justiţie interpersonală reflectă gradul în care oamenii sunt

trataţi cu politeţe, demnitate şi respect de către autorităţi şi de către terţii implicaţi

în aplicarea procedurilor sau determinarea consecinţelor. Al doilea tip, etichetat ca

justiţie informală, se centrează pe explicaţiile furnizate angajaţilor care transportă

şi difuzează informaţia, cu privire la justificarea aplicării într-un anumit fel al

procedurilor sau de ce câştigurile au fost împărţite într-un anumit mod. Acolo unde

prevalează o acurateţe a explicaţiei, nivelul perceput de justitie informală este mai

mare.

Este important ca într-o relaţie subordonat/supervizor să existe un grad înalt de

justiţie interacţională, care să reducă probabilitatea comportamentului de lucru

contraproductriv. Dacă un subordonat percepe că există injustiţie interacţională,

acesta va avea sentimente de nemulţumire fie faţă de supervizor, fie faţă de

instituţie şi, ca atare, va încerca să încline balanţa în favoarea lui. O victimă a

injustiţiei interacţionale va avea răbufniri crescute de ostilitate faţă de cel pe care îl

percepe ca trădător, care se pot manifesta prin comportament de lucru

contraproductiv şi va reduce eficacitatea comunicării organizaţionale.

Din punctul de vedere al cuiva care a auzit multe puncte de vedere ale

reclamantului, reclamaţii ale angajatului, de coşmarurile resurselor umane, dacă

veţi crea un climat de justiţie organizatorică veţi obţine o adâncire în retenţia

angajaţilor, ridicarea moralului slab, scăderea atacurilor la locul de muncă, şi vă

veţi putea baza pe forţa dumneavoastră de muncă.

Veţi dispune de lucrători motivaţi, care sunt mai putin stresaţi şi mai doritori să mai

facă ceva în plus faţă de cele convenite. Totuşi, pentru un motiv cel puţin ciudat,

Vol. I nr. 4/2009 17

justiţia organizaţională este unul dintre cele mai puţin înţelese şi utilizate unelte în

vederea creării de locuri de muncă mai bune şi mai eficiente. În mod sigur,

conceptul de justiţie organizaţională în general şi cel de justiţie interacţională în

particular, sunt concepte complexe, care necesită o aplecare serioasă asupra lor. Şi

totuşi, fără un sentiment de corectitudine percepută, angajaţii judecă recompensele

financiare mai puţin pozitiv şi multiplică impactul negativ al evenimente

provocatoare (concedierile, proiectele cu termene dificile, haosul organizatoric).

În acest articol, ne vom concentra pe justiţia interacţională, vom urmări impactul

acesteia, şi vom oferi strategii pentru crearea unui climat care va ajuta angajatorii

profite de recompense şi să reducă riscurile capitalului uman.

Faţetele justiţiei organizaţionale

La suprafaţă, justiţia organizatorică pare a fi un concept destul de simplu: a fost o

companie sau de decizie de management corectă? Cu toate acestea, nu doar

rezultatul unei decizii este cel care contează, contează, de asemenea, modul în care

decizia a fost luată şi comunicată.

Aceste trei forme de justiţie organizaţională sunt cunoscute sub numele de

distributivă, procedurală, şi justiţie interacţională.

Justiţia distributivă se referă la nivelul de bază al justiţiei, de exemplu, a fost

rezultatul unei decizii corecte? Această evaluare a corectitudinii în general implică

o comparaţie între ceea ce experimentează un angajat faţă de ceea ce se întâmplă

altora în organizaţie.

Justiţia procedurală se concentrează asupra modului în care decizia se face, de

exemplu, au fost procedurile utilizate pentru a stabili obiective, pentru luarea

deciziilor, sau pentru investigarea unei plângeri corecte? Factorii determinanţi de

justiţie procedurală includ consistenţă de aplicare, obiectivitatea factorilor de

decizie, precizia informaţiilor, căile de atac, posiblitatea de intervenţie a părţii

afectate, şi predominanţa standardelor morale.

Justiţia interacţională este foarte personală. Aceasta se referă la comportamentul

liderilor organizaţiei în desfăşurarea deciziilor lor, şi anume, modul în care aceştia

îi tratează pe cei care sunt supuşi autorităţii deciziilor şi acţiunilor lor. Cercetările

arată că efectele justiţiei interacţionale sunt independente de evaluările persoanelor

fizice, a corectitudinii în ceea ce priveşte rezultatele pe care le primesc (de

exemplu, justiţie distributivă) sau a procedurilor utilizate în alocarea acestor

rezultate (de exemplu, justiţie procedurală) şi, în anumite contexte, poate fi mai

important.

Importanţa reacţiilor la percepţia tratamentului nedrept de la locul de muncă nu

poate fi subestimată. Aşa cum a prezis de Adams (1963, 1965) prin teoria echităţii,

care a crescut în importanţă în ultimele două decenii (Miner, 2003), angajaţii

răspund de multe ori la inegalităţile salariale şi a distribuirii altor resurse prin

scăderea performanţelor sau prin creşterea absenteismului, furt, şi alte represalii

comportamentele care sunt, în general, în detrimentul funcţionării organizatorice

Jurnalul Cercetării Doctorale în Ştiinţe Economice 18

(Greenberg, 1987, 1990, 1993b). În plus faţă de locul de muncă lui Adams cu

justiţie distributivă, atenţia a fost îndreptată spre efectele mai subtile şi cu rază mai

lungă de acţiune ale justiţiei procedurale. Procedurile corecte, definite ca fiind cele

care sunt imparţiale, bazate pe informaţii exacte, aplicate în mod consecvent,

reprezentative pentru toate părţile, corectabile, şi bazate pe standarde etice

(Leventhal, 1980) sunt asociate cu astfel de rezultate pozitive organizatorice ca

angajamentele organizatorice, încrederea în supervizare (Folger şi Konovsky,

1989; Konovsky şi Cropanzano, 1991) şi comportamentul cetăţenesc (Moorman

et al., 1993). După identificarea efectelor fundamentale ale justiţiei distributive şi

procedurale, atenţia s-a mutat la efectele combinate. În special, rezultatul

procedurii x de interacţiune, prin care răspunsurile negative la rezultate incorecte

sau nefavorabile sunt atenuate de percepţiile de corectitudine procedurală, a obţinut

un sprijin empiric substanţial (Brockner şi Wiesenfeld, 1996; Greenberg, 1987).

Cel de-al treilea aspect al justiţiei organizatorice, justiţia interacţională, sau

corectitudinea percepută a tratamentului interpersonal (Bies, 1987), pare a avea o

influenţă considerabilă, dar insuficient specificată asupra percepţiei generale de

echitate. De exemplu, calitatea tratamentului interpersonal este asociată cu

acceptarea, are efect faţă de autorităţi (Tyler, 1989), şi pare să aibe o valoare

euristică în procesul de stabilire a corectitudinii procedurilor de organizare şi de

încredere în factorii de decizie (Brockner, 2002; Lind, 2001). Deşi majoritatea

cercetătorilor sunt de acord cu faptul că justiţia interacţională poate avea un impact

asupra rezultatelor organizatoric-relevante, există controverse cu privire la poziţia

sa în panteonul de justiţiei organizatorice. În timp ce justiţia interacţională este

adesea considerată o faţetă a justiţiei procedurale (Brockner şi Wiesenfeld, 1996;

Lind şi Tyler, 1988), sau un substitut pentru justiţia procedurală (Skarliki şi Folger,

1997), Greenberg ia act de faptul că "... încercările de a introduce justiţia

interacţională în justiţia procedurală poate fi privită ca o mişcare prematură spre

parcimonie"(1993b: 99). Manipulările justiţiei procedurale care implică variaţii ale

justiţiei interacţionale pot fi confundate, şi "... unele din cele mai puternice efecte

atribuite justiţiei procedurale puteau apărea atunci când justiţia interacţională, mai

degrabă decât procedurile formale au fost manipulate" (Barling şi Phillips, 1993:

650) .

Revenind la aspectele practice, justiţia interacţională pare să fie elementul esenţial

pentru a motivare, retenţie şi angajamentul organizatoric al angajatului. Într-un

studiu pe 225 de angajaţi de la două mari companii din SUA care produc vopsea de

fabricaţie, de exemplu, cercetătorii au găsit locuri de muncă în care „oamenii de

nădejde” erau criteriul de satisfacţie în motivarea angajaţilor. Cu toate acestea, nu

justiţia interacţională, în general, a fost cea care a fost cheia, ci încrederea

angajaţilor în supervizorul lor şi în corectitudinea tranzacţiilor implicite de zi cu zi.

Angajaţii, se pare, văd organizaţia prin intermediul supervizorului lor.

El este cel care explică organizaţia angajatului şi angajatul organizaţiei. Este vorba

de meritele personale, de onestitatea, imparţialitatea şi integritatea unui supervizor

cea care îl face pe angajat să mai facă ceva în plus faţă de sarcinile obişnuite în

Vol. I nr. 4/2009 19

cazul în care trebuie să termine un proiect. În cei mai simpli termeni este răspunsul

la întrebarea: Pot conta pe integritatea aceastei persoane?

Supervizorii cu stilul de conducere transformaţional sunt mai în măsură să

influenţeze angajaţii pentru a efectua sarcinile în plus, prin crearea justiţiei

procedurale şi a încrederii. Cercetătorii cred că acest lucru se datorează faptului că

liderii transformaţionali sunt capabili să inspire şi să atragă resursele angajaţilor de

corectitudine şi încredere, care obligă angajaţii să lucreze mai cu mai multă

încredere şi mai conştiincios, să facă sugestii, să efectueze sarcini suplimentare, şi

pentru a-i ajuta pe alţii.

Acest stil de conducere se caracterizează prin:

Clarificarea responsabilităţilor şi aşteptărilor

Explicarea sarcinilor care trebuie să fie efectuate şi beneficiile de auto-interes

Un sistem contingent de recompense

Adepţi care au o relaţie pozitivă cu liderul lor

Liderul intervine numai atunci când lucrurile sunt neclare

Lipsa de personalizare a relaţiei de lucru.

În plus faţă de un stil de conducere tranzacţional, angajaţii judecă simţul

corectitudinii managerului lor prin următoarele abilităţi interpersonale:

Coerenţa - măsura în care un subiect tratează constant personalul şi nu are

favoriţi

Luarea deciziilor - măsura în care un subiect este obiectiv şi imparţial în luarea

deciziilor

Empatie - măsura în care un subiect poate vedea lucrurile din perspectiva

personalului lui sau al ei

Egalitatea - măsura în care un manager îşi tratează angajaţii ca egali, mai

degrabă decât ca inferiori

Echitate relativă - cât de corect este manager un în comparaţie cu alţi manageri

din cadrul organizaţiei sale

Sprijin - măsura în care un manager asigură sprijin de fond, simbolic şi

emoţional pentru angajaţi Corectitudine-tranzacţională - măsura în care un

manager este echitabil şi non-exploatativ în schimbul de resurse cu angajaţii

Tratamentul - măsura în care un manager este respectuos şi sensibil în

interacţiunile cu personalul

Voce - măsura în care un manager este deschis pentru a da consiliere şi

feedbackul personalului.

Organizaţiile care angajează sau promovează manageri şi supervizori strict pentru

abilităţile lor tehnice, sau care nu reuşesc să furnizeze un program de management

orientat interpersonal, ca parte din procesul de promovare, pierd o oportunitate

foarte importantă şi în acelaşi timp posibilitatea de a creşte retenţia angajaţilor, de a

îmbunătăţi eficienţa managementului şi de a reduce riscul de litigii de muncă.

Jurnalul Cercetării Doctorale în Ştiinţe Economice 20

Într-un mediu de lucru, răzbunarea apare ca răspuns la încălcări ale încrederii, şi

anume, atunci când aşteptările ori comportamentul unei alte persoane nu sunt

îndeplinite, sau în cazul în care altă persoană nu acţionează în concordanţă cu

valorile cuiva. Încălcările justiţiei interacţionale au tendinţa de a evoca răspunsuri

emoţionale puternice, de la mânie la ultraj moral. Există dovezi, de exemplu, că o

concediere sau încetarea unui contract de muncă nu provoacă violenţă în ele însele.

Mai degrabă, atitudinile şi comportamentele răzbunătoare rezultă din umilirea care

se produce când încetarea contractului de muncă este produsă într-o manieră

abuzivă şi insenibilă. De fapt, numeroase studii au constatat o legătură între justiţia

distributivă (faptul că eşti concediat, de exemplu) şi represalii doar atunci când a

existat o justiţie interacţională şi procedurală scăzută.

În plus, diverse condiţii joacă un rol în încingerea temperamentelor la locul de

muncă. Reducerile de posturi, concedierile, reducerile de salarii şi beneficii,

externalizarea, toate acestea cresc presiunea la locul de muncă; cu toate acestea,

concedierile şi acţiunile disciplinare nu provoacă violenţă, de la sine; este vorba de

mândria rănită şi de pierderea stimei de sine ca factorii facvorizanţi, atunci când

acţiunile sunt efectuate de o manieră înjositoare. Este vorba de interacţiunea între

justiţia distributivă, procedurală şi interacţională cea care conduce la represalii;

tratamentul neloial sau nedrept în timpul de concedierii poate fi "ultima picătură"

care va face angajatul concediat să treacă de la gândurile la represalii la agresiune

reală.

Agresiunea la locul de muncă nu apare doar ca răspuns la abuz sau umilire

interpersonală, ea poate fi, de asemenea, rezultatul încălcării percepute a unui

contract psihologic, adică, a credinţei angajatului că este plătit pentru promisiuni,

sau că există obligaţii reciproce. De exemplu, estimările de vânzări nerealiste

pentru un candidat în timpul unui interviu de angajare, pot conduce la un sentiment

de trădare şi de nedreptate. Încălcarea contractului psihologic este un proces care

conţine elemente de promisiuni neîndeplinite care privează angajaţii de rezultatele

dorite (justiţie distributivă) şi elemente care afectează calitatea tratamentului

experienţei angajatului (justiţie procedurală).

Din păcate, acest lucru se întâmplă prea des. Într-un studiu pe 128 de studenţi

MBA, care au acceptat deja o ofertă de angajare, 54,8% din subiecţi au raportat că

angajatorul lor a încălcat contractul psihologic. Această încălcare a fost

semnificativ mai mică raportată la scorurile unui studiu de încredere a angajaţilor

în angajatorul lor şi la satisfacţia angajaţilor. Rezultatele au sugerat, de asemenea,

că angajaţii care au părăsit compania au raportat un grad mai mare de încălcare a

contractului decât cei care nu şi-au părăsit angajatorul.

Aparent, aceste încălcări se întind pe toate domeniile de ocupare a forţei de muncă

(de exemplu, de formare, de compensare, de promovare, natura locului de muncă,

siguranţa locului de muncă, feedbackul, managementul schimbării,

responsabilitate).

Vol. I nr. 4/2009 21

Orice organizatie care doreşte să exceleze trebuie să se asigure că a relaţia angajat-

angajator este exprimată în afara relaţiei economice, şi anume în arena emoţională.

Resursele umane pot juca un rol vital în justiţia organizatorică:

• Verifică toate politicile şi normele de lucru pentru a se asigura că există proceduri

care crează echitate. Cei mai importanţi angajaţi se centrează pe plată, diversitate,

etc. În consecinţă, trebuie monitorizate deciziile luate în punerea în aplicarea

acestor norme generale şi practici de lucru pentru a asigura vizibilitatea echităţii şi

egalităţii în toate deciziile managementului şi ale supervizorilor referitoare la

angajaţi şi activitatea lor.

• Includerea abilităţilor de conducere şi interpersonale în programul de dezvoltare

al organizaţiei, incluzând evaluări de 360 de grade de către subordonaţi, colegi şi

de management.

• Pentru a proteja împotriva încălcărilor neintenţionate ale contract psihologic,

asiguraţi-vă că toţi candidaţii au o fişă de post realistă (de exemplu, oferind o

descriere a locului de muncă, organizarea, şi oportunităţile, incluzând atât

caracteristici pozitive cât şi negative). Gradul de sinceritate demonstrat pentru

angajaţi în cursul procesului de selecţie va forma percepţii de sprijin şi de justiţie,

printre cei care sunt în cele din urmă, angajaţi.

Pentru că angajaţii sunt angajaţi într-o răzbunare, cel mai probabil, fie pentru a

restabili echitatea sau exprima sentimentele de nemulţumire intensă, ar trebui

oferite mai multe căi pentru a soluţiona plângerile acestora (şi sentimentele

asociate lor). De exemplu, în plus faţă de procedurile formale de plângere, ar trebui

angajată echipa de HR pentru a da consultaţii informale în timpul restructurării

organizatorice şi de a oferi servicii de plasare în alte locuri de muncă în timpul

concedierilor.

Concluzii

Ca o chestiune practică, este important ca presupunerea că relaţia angajat /angajator

este în primul rând de natură economică să fie re-evaluată. Un management bun,

care să promoveze comportamente de cooperare şi constructive mai degrabă decât

de retragere şi represalii, cere ca managerii să recunoască în final - calitatea

tratamentului interpersonal în schimburile sociale cu salariaţii, sau justiţia

interacţională, contează. Bunul simţ, precum şi rezultatele empirice, indică faptul

că atât rezultatele economice cât şi cele sociale de schimb trebuie să fie percepute

ca fiind suficiente şi corecte pentru a promova atitudini şi comportamente care să

contribuie la funcţionarea organizatorică.

Autorul columbian Gabriel García Márquez, a spus o dată, "Justiţia merge

şchipătând...dar tot acolo ajunge." Organizaţiile care crează un sentiment de justiţie

organizatorică se vor bucura de recompensele capitalului uman prin motivare

îmbunătăţită, retenţie şi mai puţine litigii de muncă. Din pacate, companiile care nu

Jurnalul Cercetării Doctorale în Ştiinţe Economice 22

pot, se găsi ele însele şchiopătând, în timp ce concurenţa sprintează spre înainte,

spune Joni Johnston şi acest lucru este mai mult decât evident.

În conformitate cu Andrew Sawers, în "Financial Director", 2008, companiile se

găsesc într-o mare dificultate, nu numai în menţinerea angajaţilor, ci şi în

recrutarea lor. Dificultăţile în a păstra un personal înalt calificat sunt cele mai

mari îngrijorări ale companiilor care se află faţă-n faţă cu globalizarea, în

conformitate cu un studiu efectuat de Economist Intelligence Unit, în numele

firmei de consultanţă de afaceri EquaTerra. Directorii nord-americani au citat

globalizarea ca pe o provocare de a păstra personalul calificat cu 12% mai mult

decât cei europeni. Directorii vest-europeni au găsit ca provocare primară

finanţarea expansiunii pe noi pieţe.

Riscul litigiilor de muncă. Complexitatea crescândă a legislaţiei au făcut ca 39%

din respondenţi, directori, la un raport întocmit de către Lloyds, o companie de

asigurare, să fie de acord cu faptul că riscul de a avea litigii de muncă ar putea

creşte costurile produselor sau serviciilor în următorii trei ani.

Soluţia se află în relaţia complexă angajat-angajator şi gradul de încredere pe care

şi-l acordă reciproc. Justiţia interacţională în cadrul unei organizaţii pot face

diferenţa reală. Cei care vor să supravieţuiască în condiţiile de criză şi globalizare

actuale trebuie să-şi ia orice măsură necesară pentru ca afacerea lor să continue să

„trăiască”.

Bibliografie

Adams, J. S. 1963. "Toward an Understanding of Inequity." Journal of Abnormal

and Social Psychology 67: 422-436.

Aryee, S., Chen, Z., Sun, L., & Debrah, Y. (2007, January). Antecedents and

outcomes of abusive supervision: Test of a trickle-down model. Journal of

Applied Psychology, 92(1), 191-201.

Barling, J. and M. Phillips. 1993. "Interaction, Formal and Distributive Justice in

the Workplace: An Exploratory, Study." The Journal of Psychology 127 (6):

649-656.

Baron, R. A., & Neuman, J. H. (1996). Workplace violence and workplace

aggression: Evidence on their relative frequency and potential causes.

Aggressive Behavior, 22, 161–173.

Bies, R.J. 1987. "The Predicament of Injustice: The Management of Moral

Outrage. In Research in Organizational Behavior (Vol. 9). Eds. L. L.

Cummings and B. M. Staw. Greenwich, CT:JAI Press. pp. 289-319.

and B. M. Wiesenfeld. 1996. "An Integrative Framework for Explaining Reactions

to Decisions: Interactive Effects of Outcomes and Procedures." Psychological

Bulletin 120(2): 189-208.

Vol. I nr. 4/2009 23

Cropanzano, R. and R. Folger. 1991. "Procedural Justice and Worker Motivation."

In Motivation and Work Behavior (Sth ed.). Eds. R. M. Steers and L. W.

Porter. New York, NY: McGraw Hill. pp. 131-143.

Folger, R. and M. A. Konovsky. 1989. "Effects of Procedural and Distributive

Justice on Reactions to Pay Raise Decisions." Academy of Management

Journal 32: 115-130.

Greenberg, J. 1993a. "The Social Side of Fairness: Interpersonal and Informational

Classes of Organizational Justice. In Justice in the Workplace: Approaching

Fairness in Human Resource Management. Ed. R. Cropanzano. Hillsdale, NJ:

Lawrence Erlbaum. pp. 79-103.

Leventhal, G. S. 1980. "What Should be Done with Equity Theory?" In Social

Exchange: Advances in Theory and Research. Eds. K.J. Gergen, M. S.

Greenberg and R. H. Willis. New York, NY: Plenum Press. pp. 27-55.

Lind, E. A. 2001. "Fairness Heuristic Theory: Justice Judgements as Pivotal

Cognitions in Organizational Relations." In Advances in Organizational

Justice. Eds. J. Greenberg and R. Cropanzano. Stanford, CA: Stanford

University Press. pp. 56-88.

and T. R. Tyler. 1988. The Social Psychology of Procedural Justice. New York,

NY: Plenum Press.

Miner, J. B. 2003. "The Rated Importance, Scientific Validity, and Practical

Usefulness of Organizational Behavior Theories: A Quantitative Review."

Academy of Management Learning and Education 2: 250-268.

Moorman, R. H., B. P. Niehoff and D. W. Organ. 1993. "Treating Employees

Fairly and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: Sorting the Effects of Job

Satisfaction, Organizational Commitment, and Procedural Justice." Employee

Responsibilities and Rights Journal 6: 209-225.

Sawers, Andrew, “Financial Director”, 28 Mai 2008,

http://www.financialdirector.co.uk/financial-director/analysis/2217627/

financial-directions-june, accesat pe 3 Mai 2009

Skarlicki, D. P. and R. Folger. 1997. "Retaliation in the Workplace: The Roles of

Distributive, Procedural, and Interactional Justice. Journal of Applied

Psychology 82: 434-443.

Tyler, T. R. 1989. "The Psychology of Procedural Justice: A Test of the Group-

value Model." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 57: 830-838.

Work Relationships,

http://www.workrelationships.com/site/articles/employeeretention.htm,

accesat pe 3 Mai 2009.

Jurnalul Cercetării Doctorale în Ştiinţe Economice 24

ELEMENTE NOI PRIVIND REPROIECTAREA

SISTEMELOR MANAGERIALE ÎN CONTEXTUL

TRECERII LA ECONOMIA BAZATĂ PE CUNOŞTINŢE

Ana-Maria Grigore Academia de Studii Economice din Bucureşti, România

Rezumat

Scopul acestei lucrări este de a aborda în mod sistematic problematica reproiectării

sistemelor manageriale, care a devenit o temă majoră în teoria şi practica managerială

actuală. Odată cu apariţia conceptului şi a practicilor de „Knowledge Management”

metodologia de reproiectarea managerială va suferii câteva modificări importante.

Reproiectarea sistemului managerial afectează toate categoriile de angajaţi. Este

important ca fiecare dintre aceştia să cunoască obiectivele strategice pentru a contribui în

aceeaşi direcţie la obţinerea performanţelor.

În ultimii ani s-a putut constata că o mare parte din firmele competitive din ţările

dezvoltate au început să manifeste abordări economice şi manageriale diferite de cele din

deceniul trecut, având strânsă legătură cu schimbările tehnice şi tehnologice, în special

evoluţiile informatice şi comunicaţionale. Aceste evoluţii au determinat funcţionalităţii şi

performanţe diferite de cele din perioada anterioară.

În prezent există numeroase lucrări care prezintă o varietate de abordări teoretico-

metodologice ale economiei, organizaţiei şi managementului bazate pe cunoştinţe. Articolul

abordează câteva din cauzele apariţiei acestora, care au legătură cu schimbările deosebit

de complexe care se produc în toate domeniile, stadiul incipient în care se află economia

bazată pe cunoştinţe, gradul şi natura diferită a pregătirii, informării, obiectivelor şi

resurselor.

În final, lucrarea va conţine propuneri privind modificarile ce trebuie realizate în

metodologia de reproiectare managerială.

Cuvinte-cheie: reproiectare managerială, economie bazată pe cunoştinţe, management

bazat pe cunoştinţe, performanţe economice, performanţe manageriale

Clasificare JEL: L25, L22, M10, D80, O15

Introducere

“Reengineeringul” sau reproiectarea managerială este un termen folosit destul de

des încă din anul 1993, când a fost introdus pentru prima oară de Hammer într-un

articol intitulat ˝Reengineering work: Don´t Automate, Obliterate˝

(Reengineeringul activităţii: nu automatizaţi, eliminaţi). În condiţiile actuale, de

schimbări mondiale semnificative, conceptul devine esenţial pentru succesul în

Vol. I nr. 4/2009 25

afaceri, pentru organizarea optimă a activităţii, acordată priorităţilor şi rigorilor

externe.

Reproiectarea managerială sporeşte performanţele organizaţiei în unul sau mai

multe domenii de activitate, prin schimbarea radicală a modului de lucru.

Companiile nu trebui să-şi schimbe profilul de activitate, în schimb trebuie să-şi

modifice semnificativ procesele din care constau această activitate - sau chiar

înlocuind vechile procese.

Reproiectarea managerială - este o atitudine de tipul ˝totul sau nimic˝, care conduce

la rezultate pozitive pentru companie. Nu există companie în România, şi în restul

lumii care să nu dorească o organizare flexibilă pentru a se adapta repede la

condiţiile mereu în schimbare ale pieţei, pentru a depăşi concurenţa, să fie

inovativă pentru a-şi menţine produsele şi serviciile la zi din punct de vedere

tehnologic şi suficient de dezvoltată pentru a oferi calitate şi servicii sporite pentru

client.

Dar şi în ciuda acestor obiective, companiile româneşti sunt în majoritatea lor

¨încete¨, ¨ruginite¨, rigide, încâlcite, necompetitive, necreative, ineficiente,

nepăsătoare faţă de nevoile clienţilor, interesate de profitul propriu, sau lucrează în

pierdere.

Lucrarea îşi propune să analizeze şi să propună modificările cele mai importante

care pot apărea în metodologia de reproiectare managerială.

1. Reproiectarea managerială în contextul trecerii la economia bazată

pe cunoştinţe

Tehnologiile avansate, dispariţia graniţelor între pieţele naţionale şi modificarea

cerinţelor clienţilor, care au în prezent posibilitatea de alegere mult mai mare decât

au avut vreodată, au condus la efectul combinat că obiectivele, metodele şi

principiile organizatorice de bază ale firmelor româneşti au devenit învechite.

Pentru a deveni competitive, soluţia nu este să lucreze mai intens, ci a învăţa să

lucreze altfel. Asta înseamnă că firmele şi salariaţii lor trebuie să se dezobişnuiască

de multe dintre principiile şi tehnicile care le-au adus succes un timp atât de

îndelungat.

În prezent pot fi identificate o serie de tendinţe care se manifestă în contextul

trecerii la economia bazată pe cunoştinţe, şi anume:

- Sporirea flexibilităţii dimensionale a organizaţiei, privitoare la volumul de

activitate desfăşurate şi al resurselor folosite – capacităţi de producţie, forţa de

muncă, capitalul, a structurii organizaţiei, referitoare la portofoliul afacerilor

desfăşurate, la nomenclatorul produselor şi serviciilor, şi creşterea flexibilităţii

funcţionale, referitoare la sistemul de conducere strategică, mecanismele

decizionale, sistemul de planificare strategică, control şi evaluare.

- Dispersia geografică a activităţilor organizaţiei. Aceasta a devenit în ultimul

timp o caracteristică definitorie a firmelor mari, existând toate motivele care să

Jurnalul Cercetării Doctorale în Ştiinţe Economice 26

îndreptăţească previziunea ce se va amplifica şi adânci în viitor. Tendinţa aceasta

constă în esenţă în localizarea diferită a activităţilor funcţionale, cum ar fi

cercetarea-dezvoltarea, planificarea strategică, financiară, faţă de activităţile de

producţie şi a celor auxiliare.

- Accentuarea rolului tehnologiilor intelectuale în conducerea şi funcţionarea

organizaţiilor. Aceasta va antrena modificări semnificative ale caracterului şi

conţinutului muncii, care vor reclamă creşterea generală a nivelului de cultură, de

cunoaştere şi de aprofundare a problemelor de către manageri şi de către toţi

ceilalţi salariaţi ai firmei.

- Profesionalizarea crescândă a managementului. Se doreşte practicarea unui

management profesionist, în care se remarcă absenţa din cadrul actelor manageriale

a elementelor de improvizaţie, fundamentării precare a deciziilor,

comportamentului autocratic, indisponibilităţii pentru dialog şi a lipsei de

receptivitate la nou.

- Extinderea informatizării economiei şi societăţii. Aceasta va asigura

dobândirea de către companie a unei flexibilităţi crescânde a activităţii desfăşurate,

creşterea capacităţii sale de reacţie, optimizarea modului de alocare a resurselor,

creşterea semnificativă a eficienţei întregii activităţi.

Tendinţele enumerate mai sus vor determina organizaţiile să îşi redefinească

propria cultură prin procese de reproiectare organizaţională şi modificări de

strategie.

Modernizarea managerială nu este doar o modă a perioadei pe care o traversăm, ci

o necesitate pentru asigurarea unor parametri calitativi superiori sistemelor

microeconomice de management. Demersul strategic de amploare ce răspunde unei

asemenea necesităţi îl reprezintă reproiectarea managementului organizaţiei.

Punctul de pornire şi în acelaşi timp, o primă etapă a reproiectării sistemelor

manageriale o reprezintă diagnosticarea viabilităţii economico-financiare şi

manageriale a organizaţiei, ce are ca scop evidenţierea principalelor puncte forte

şi disfuncţionalităţi şi, pe aceeaşi bază, formularea de recomandări, axate pe

cauzele generatoare de abateri pozitive şi negative.

Cea de-a doua etapă are în vedere precizarea tipului de strategie pe care

organizaţia şi-l alege în funcţie de anumite criterii şi de potenţialul economico-

financiar de care dispune. În final, este necesară elaborarea strategiei după o

metodologie adecvată, din care să nu lipsească: precizarea locului şi a rolului

organizaţiei în societatea în care activează, stabilirea obiectivelor strategice,

precizarea modalităţilor de realizare a acestora, dimensionarea resurselor ce

urmează a fi angajate pentru realizarea obiectivelor şi stabilirea termenelor

intermediare şi finale.

Etapa cea mai complexă o constituie reproiectarea propriu-zisă, ce se recomanda

a fi realizată într-o anumită ordine, în funcţie de locul şi rolul fiecărei componente

manageriale şi de legăturile dintre acestea în cadrul sistemului de management.

Vol. I nr. 4/2009 27

Debutul trebuie realizat de implementarea unor sisteme, metode şi tehnici

manageriale, cu ajutorul unor metodologii specifice, puse la dispoziţie de teoria

managementului.

În continuare, în funcţie de cerinţele exprimate de instrumentarul managerial

pentru care s-a optat, se trece la reproiectarea subsistemului decizional, ce

presupune atât precizarea tipologică a deciziilor ce urmează a fi adoptate, pe

niveluri ierarhice, cât şi stabilirea mecanismelor decizionale ce asigură adoptarea

lor.

Procesele decizionale reclamă informaţii, vehiculate pe fluxuri şi circuite

ascendente, descendente sau oblice, cu ajutorul unor proceduri şi mijloace de

tratare adecvate. Toate acestea aparţin subsistemului informaţional, a cărui

reproiectare trebui să asigure condiţiile necesare pentru îndeplinirea funcţiilor-

decizională, operaţională şi de documentare- ce-i revin în sistemul de management.

Ultima componentă managerială supusă unui proces complex de modernizare o

reprezintă subsistemul organizatoric, abordat ca organizare procesuală şi

organizare structurală.

Reproiectarea propriu zisă a sistemului managerial este urmată, firesc, de

implementarea soluţiilor manageriale conturate şi evaluarea eficienţei sistemului de

management reproiectat.

2. Modificări apărute în cadrul reproiectării manageriale

Conceptul de ¨knowledge management¨- management bazat pe cunoştinţe

favorizează existenţa unui cadru organizat, destinat integrării noilor tendinţe

strategice şi manageriale apărute în ultimii ani.

Analizele efectuate de specialişti au identificat câteva aspecte majore care trebuie

luate în considerare de către stakeholderi organizaţiei în operaţionalizarea

managementului bazat pe cunoştinţe. Între aceste se numără (Nicolescu, 2003,

pp. 288):

Acţionarea asupra culturii organizaţionale în vederea adoptării

managementului bazat pe cunoştinţe.

Încurajarea resurselor umane să-şi partajeze cunoştinţele.

Obţinerea suportului din partea liderilor din firmă pentru promovarea

managementului bazat pe cunoştinţe.

Asigurarea managementului informaţilor.

Determinarea beneficilor rezultate din tratarea cunoştinţelor.

Rezolvarea problemelor generate de resursele limitate alocate pentru tratarea

cunoştinţelor.

Sprijinirea transferului celor mai bune practici în cadrul organizaţiei.

Asistarea şi sprijinirea comunităţii bazate pe cunoştinţe.

Luarea în considerare a managementului bazat pe cunoştinţe de către

ansamblul stakeholderilor firmei.

Jurnalul Cercetării Doctorale în Ştiinţe Economice 28

Din examinarea elementelor de mai sus rezultă că aspectele-cheie de care depind

conceperea şi operaţionalizarea eficace a managementului bazat pe cunoştinţe sunt

de natură umană în proporţie de 60% şi de natură economică în proporţie de 20%.

Ţinând seama de rezultatul acestor analize în cadrul metodologiei de reproiectare

managerială componenta de management al resurselor umane va avea o importanţă

sporită în contextul trecerii la economia bazată pe cunoştinţe.

În cadrul metodologiei de reproiectare managerială vor apărea următoarele

modificări:

În metodologia de realizare a strategiei apar procese si corelări noi care

ţin seama de două elemente importante: cunoştinţele devin cea mai importanta

resursă strategică a firmei şi învăţarea devine cea mai importantă capacitate a

organizaţiei. Pe lângă acestea mai apar frecvent alte două elemente de esenţă şi

anume: firma îşi finalizează activităţile în produse-cunoştinţe şi servicii-cunoştinţe

şi realizarea inovării devine critică pentru organizaţie, condiţionându-i nu numai

performanţele, dar uneori chiar şi existenţa.

Cele mai multe caracteristici ale strategiei evidenţiază că cea mai mare parte dintre

ele se referă nemijlocit la factorul uman. Potrivit specialiştilor niponi Nomura şi

Ogiwara (Nicolecu, 2003, pp. 219) , caracteristicile strategiei, şi în primul rând

focalizarea pe cunoştinţe şi obiectivele previzionate, este necesar să fie vizibile

pentru toţi stakeholderii companiei.

În componenta metodologico-managerială se vor introduce noi sisteme şi

metode de management specifice managementului bazat pe cunoştinţe. Gama

sistemelor, metodelor şi tehnicilor manageriale utilizate în cadrul firmelor bazate

pe cunoştinţe, se vor clasifica în funcţie de obiectivele specifice în două categorii

(Nicolecu, 2003, pp. 228):

Sisteme, metode, tehnici manageriale utilizate şi în perioada precedentă, al

căror conţinut a fost remodelat în vederea valorificării multiplelor funcţii

ale cunoştinţelor.

Modele, sisteme, tehnici, proceduri manageriale specifice managementului

bazat pe cunoştinţe care au fost concepute în mod expres pentru a realiza

anumite activităţi de tratare a cunoştinţelor. Printre aceste se vor număra:

▪ sisteme de păstrare a cunoştinţelor care depozitează şi formalizează

cunoştinţele experţilor, astfel încât să poată fi partajate cu alţi

specialişti;

▪ sisteme de utilizare a cunoştinţelor, care selecţionează şi reţin

cunoştinţele în vederea reutilizării lor în soluţionarea problemelor care

se repetă şi a noilor probleme;

▪ repertoare de cunoştinţe care organizează şi distribuie cunoştinţele;

▪ sisteme de descoperire a cunoştinţelor care creează noi cunoştinţe prin

implementarea de algoritmi inteligenţi;

▪ etc.

Vol. I nr. 4/2009 29

Componenta de management al resurselor umane tinde să promoveze şi

să se bazeze tot mai mult pe cunoştinţe. Managementul resurselor umane bazat

pe cunoştinţe este o componentă esenţială a managementului bazat pe cunoştinţe,

care va prevala în viitor şi va condiţiona sustenabilitatea organizaţilor.

Învăţarea continuă reprezintă un proces esenţial, prin care se

caracterizează managementul resurselor umane bazat pe cunoştinţe,

transformând compania în organizaţie care învaţă (learning organization). În planul

managementului resurselor umane, reflectarea acestor evoluţii o constituie

derularea unor intense şi specifice procese de pregătire a stakeholderilor

organizaţiei, cu accent asupra salariaţilor săi.

Reproiectarea subsistemului managementului resurselor umane trebuie

să aibă în vedere identificarea cunoştinţelor şi informaţiilor pe care le deţin

salariaţii şi ceilalţi stakeholderi ai companiei, furnizarea cunoştinţelor necesare

persoanelor şi grupurilor din cadrul organizaţiei în perioada optimă.

În cadrul componentei informaţionale se vor reţine acele informaţii care

prin utilizarea lor vor genera valoare adăugată transformându-se astfel în

cunoştinţe. De asemenea se urmăreşte integrarea oamenilor şi fluxurilor de muncă

cu aplicaţiile informatice, generarea de performanţe economice cu aplicaţiile

informatice, trainingul şi motivarea utilizatorilor tehnicii şi tehnologiilor

informatice.

Componenta organizatorică va suferi modificări atât la nivel structural

cât şi procesual. Premisa reconceperii sistemului organizatoric al organizaţiei o

reprezintă conectarea cunoştinţelor cu procesele de muncă şi a proceselor de muncă

cu cunoştinţele. Se pune astfel problema realizării unei simbioze între cunoştinţe şi

celelalte resurse ale organizaţiei, între procesele specializate de tratare a

cunoştinţelor şi celelalte procese de muncă. Noua organizare şi mediul

cunoştinţelor se caracterizează prin mutaţii esenţiale la nivelul componentelor

organizatorice primare: funcţiile şi posturile. Dintre rolurile şi funcţiile axate pe

managementul cunoştinţelor voi enumera câteva (Nicolecu, 2003, pp. 250):

Managerul şef de cunoştinţe (elaborează strategii, exercitarea leadershipului), şeful

echipei de promovare a cunoştinţelor, practicienii cunoştinţelor (broker de

cunoştinţe, cercetătorul, analistul, editorul, sintetizatorul), specialişti bazaţi pe

cunoştinţe (liderul de cunoştinţe) etc.

Schimbări majore se vor produce şi la nivelul locurilor de muncă, la

nivelurile: Cunoştinţelor, creativităţii şi inovării care devin esenţa proceselor de

muncă la toate nivelurile organizaţiei;

Parteneriatului şi dialogului în cadrul cărora producerea şi proprietatea

asupra inovării sunt distribuite şi partajate pe scară largă;

Amplasării persoanelor care derulează procese de muncă şi a modalităţilor

de exercitare a acestora, pe lângă modalităţile clasice prin apariţia de noi

forme de muncă;