ACTUALITÃÞI ÎN DIAGNOSTICULªI TRATAMENTUL … · diagnostic pozitiv cor ect, conducând la...

Transcript of ACTUALITÃÞI ÎN DIAGNOSTICULªI TRATAMENTUL … · diagnostic pozitiv cor ect, conducând la...

87

ACTUALITÃÞI ÎN DIAGNOSTICUL ªI TRATAMENTULMETASTAZELOR CUTANATE ALE MELANOMULUI

AN UP TO DATE IN THE DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF MELANOMA SKIN METASTASES

LAURA MARIA LUCIA PAPAGHEORGHE*, ANA-MARIA FORSEA*, CÃLIN GIURCÃNEANU*

Rezumat

Melanomul este unul dintre cele mai metastazantecancere, iar morbiditatea ºi mortalitatea corespunzãtoaremelanomului cutanat sunt determinate în principal deboala metastaticã. Metastazele cutanate sunt un fenomenîntâlnit frecvent în istoria naturalã a bolii, atât precoce câtºi în fazele tardive, prognosticul lor fiind semnificativsuperior metastazelor viscerale. Mecanismele procesuluimetastatic sunt foarte complexe, incomplet elucidate, ºiimplicã o serie de factori intrinseci ºi extrinseci tumorali.Contextul gazdei joacã un rol fundamental pentrufacilitarea sau inhibarea dezvoltãrii tumorale ºi ametastazãrii în funcþie de stadiul evolutiv al tumorii.Metastazele cutanate pun frecvent probleme de diagnosticdiferenþial, clinic, dermatoscopic ºi histopatologic,implicând entitãþi atât benigne, cât ºi maligne. În prezentsunt disponibile numeroase opþiuni terapeutice, locale ºisistemice, la alegerea cãrora trebuie þinut cont de extensiabolii, prezenþa afectãrii sistemice ºi comorbiditãþilepacientului. Terapiile au rol curativ dacã metastazelecutanate reprezintã singura manifestare a bolii, trata-mentul chirurgical reprezentând standardul de aur, sau rolpaliativ în cazul leziunilor extinse, inoperabile sau însoþinddiseminarea sistemicã.

Lucrarea de faþã realizeazã o trecere în revistã a datelorºtiinþifice actuale cu privire la metastazele cutanate alemelanomului, din punctul de vedere al mecanismelormetastazãrii, aspectelor clinico-patologice, al problemelor

Summary

Melanoma is one of the most metastasizing cancers,and its morbidity and mortality are mostly determined bymetastatic disease. Cutaneous metastases are a frequentlyencountered event in the natural history of the disease, inthe early as well as in the late stages, with a significantlyhigher survivial rate than visceral metastases. Themechanisms that drive the metastatic process are verycomplex, incompletely clarified, and involve a series ofintrinsic and extrinsic tumoral factors. The host's settingplays a fundamental role for enabling or inhibiting tumorgrowth and metastasis in accordance to the tumor'sdevelopmental phase.Skin metastases frequently raisedifferential diagnosis issues, from a clinical, dermato-scopic and histopatological point of view, involving bothbenign and malignant entities. Presently, numeroustherapeutic options are available, local and systemic, onwhose choice one must take into account the diseaseextension, the presence of systemic disease and thepatient's comorbidities. Available treatments have acurative role if cutaneous metastases represent the solemanifestation of the disease, surgical treatmentremaining the gold standard, or a palliative role forextensive, inoperable lesions or accompaning systemicdissemination.

This paper is a review of present-day scientific data ofmelanoma skin metastasis, regarding the mechanisms ofmetastasis, the clinical and pathological aspects, and of

* Clinica de Dermatologie Oncologicã ºi Alergologie, Spitalul Universitar de Urgenþã ELIAS, Bucureºti, România.Oncology Clinic of Dermatology and Allergology, University Hospital Emergency ELIAS, Bucharest, Romania.

REFERATE GENERALEGENERAL REPORTS

88

DermatoVenerol. (Buc.), 60: 87-108

Introducere

Metastazarea tumoralã este principala cauzãde deces a pacienþilor oncologici, iar melanomuleste unul dintre cele mai metastazanteneoplasme. Deºi reprezintã mai puþin de 5% dintumorile maligne cutanate, i se alocã 75% din decesele cauzate de cancere cutanate [1].Metastazele cutanate ale melanomului reprezintãun eveniment întâlnit frecvent în istoria naturalãa bolii ºi se poate produce atât precoce cât ºi înfazele tardive ale afecþiunii. În acelaºi timp, înrândul pacienþilor cu metastaze cutanate de oriceetiologie, melanomul este cea mai frecventîntâlnitã malignitate în rândul bãrbaþilor ºi ceade-a doua în rândul femeilor, dupã neoplasmulmamar [2]. Se estimeazã cã aproximativ 16,5%dintre toþi pacienþii diagnosticaþi cu melanomprimar vor dezvolta metastaze, iar dintre cei cumelanom metastatic visceral circa 50% vor avea ºimetastaze cutanate [3]. Diagnosticul precoce almetastazelor cutanate de melanom este impor-tant pentru stadializare ºi estimare prognosticã.Este deosebit de importantã stabilirea tipului demetastazã, respectiv recurenþã localã, metastazãîn tranzit sau la distanþã, datoritã impactuluiasupra prognosticului [4]. Mai mult decât atât,metastazele cutanate au o supravieþuire netsuperioarã metastazelor viscerale la 1, 5 ºi 10 ani[4] .

Morbiditatea ºi mortalitatea melanomuluicutanat sunt determinate în principal de boalametastaticã, care se poate produce chiar ºi încazul tumorilor subþiri [5]. Aspectele clinice ºihistopatologice heterogene ale metastazelorcutanate pot pune probleme importante dediagnostic diferenþial ce ar putea întârzia undiagnostic pozitiv corect, conducând la agravareaprognosticului. În prezent existã numeroaseopþiuni terapeutice, atât locale, cât ºi sistemice, acãror alegere depinde de localizarea ºi numãrulleziunilor, dar ºi de vârsta pacientului, prezenþaafectãrii sistemice ºi comorbiditãþile acestuia.

Introduction

Tumor metastasis is the main cause of deathin oncologic patients, and melanoma is one of themost metastatic tumors. Although it representsless than 5% of the malignant tumors of the skin,it is responsible of 75%skin cancer-related deaths[1]. Melanoma skin metastases are a frequentoccurrence the natural history of the disease andcan arise early as well as in the late stages of thedisease. Mean while, melanoma is the mostfrequent malignant tumor in patients with skinmetastases of all types among men, and thesecond most frequent among women, after thebreast cancer [2]. Roughly 16.5% of all patientsdiagnosed with primary melanoma will developskin metastases, and 50% of the ones withvisceral metastatic melanoma will havecutaneous metastases as well [3]. Early diagnosisof skin metastases is important for staging andoutcome estimation. It is most important toestablish the type of metastasis, local recurrence,in transit or distant metastasis, as a result ofimpact on the outcome [4]. Moreover, skinmetastases have a significantly higher survivalrate than visceral metastases at 1, 5 and 10years [4].

Morbidity and mortality of skin melanomaare determined mainly by metastatic disease,which can occur even in the case of thin tumors[5]. Heterogeneous clinical and histopathol-ogyaspects of skin metastases can make thedifferential diagnosis problematic, which maydelay a correct positive diagnosis, leading to aworse prognosis. To date, there are numeroustherapeutic options, local as well as systemic,treatment choice depending on the location andthe number of the lesions, but also on thepatient’s age, systemic disease and comorbidities.

de diagnostic clinic ºi diferenþial al acestora, precum ºi alopþiunilor terapeutice disponibile în prezent.

Cuvinte cheie: melanom, metastaze cutanate,mecanisme de metastazare, tratamentul melanomului.

Intrat în redacþie: 22.04.2015Acceptat: 29.05.2015

Received: 22.04.2015Accepted: 29.05.2015

clinical and differential diagnosis issues, as well as of thetherapeutic options available today.

Key words: melanoma, skin metastases, mechanism ofmetastasis, melanoma treatment.

89

DermatoVenerol. (Buc.), 60: 87-108

Lucrarea de faþã realizeazã o trecere în revistãa datelor ºtiinþifice actuale privind metastazelecutanate ale melanomului cutanat, din punctulde vedere al mecanismelor metastazãrii, alaspectelor clinico-patologice, al problemelor dediagnostic clinic ºi diferenþial al acestora precumºi al opþiunilor terapeutice disponibile.

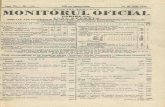

1. Mecanisme de metastazare

Formarea tumorii primare a fost ilustratã decele mai multe ori ca un fenomen liniar, însãdiverse observaþii recente sugereazã cã nu esteîntotdeauna cazul. Modelul clasic presupune cãtrecerea de la melanocitele normale la melanomulmetastatic se face parcurgând fazele de: nevmelanocitar/nev displazic, melanom in situ, cucreºtere radialã, creºtere verticalã a tumoriiprimare ºi în final metastazare. În prezent însãmai mulþi autori considerã cã progresia tumoralãliniarã este doar unul dintre modelele evolutive ºicã parcurgerea tuturor paºilor nu este necesarã încazul tuturor tumorilor [6] (Fig. 1). Studiilerecente au arãtat cã diseminarea celularã de la

This paper is a review of present-dayscientific data of melanoma skin metastasis,regarding the mechanisms of metastasis, theclinical and pathological aspects, and clinical anddifferential diagnosis issues, as well as of thetherapeutic options available today.

1. Mechanisms of metastasis

The development of the primary tumor wasillustrated mostly as a linear phenomenon, butrecent observations suggest that such is notalways the case. The classical model hypothesizesthat the transformation of normal melanocytes tometastatic melanoma covers the following steps:melanocytic nevus/dysplastic nevus, in situmelanoma, with radial growth, vertical growth ofthe primary tumor and finally metastasis.Presently, several authors consider that lineartumor progression is only one of thedevelopment models and that covering all stepsis not necessary [6]. Recent studies showed that

Fig. 1. Progresia tumoralã liniarã ºi non-liniarã (Adaptat dupã WE Damsky, N.T.a.M.B., Melanoma metastasis: new conceptsand evolving paradigms. Oncogene 2014. 33: p. 2413–2422)

Melanocit

? ? ? ?

Nev Nev atipic Melanom in situ Melanom

Diseminare celularã

Fig. 1. Linear and non-linear tumor progression (adapted after WE Damsky, N.T.a.M.B., Melanoma metastasis: new conceptsand evolving paradigms. Oncogene 2014. 33: p. 2413-2422)

Melanocytes

? ? ? ?

Nev Nev atypical Melanoma in situ Melanoma

Dissemination cell

90

DermatoVenerol. (Buc.), 60: 87-108

nivelul leziunii primare se poate produce ºiprecoce în fazele in situ, ale melanoamelor ºi nuneapãrat doar în cazul tumorilor invazive. Acestaar corespunde de altfel gradului mare demobilitate intrinsecã melanocitelor normale, carese pot regãsi frecvent ºi în afara membraneibazale, de exemplu în derm, ganglionii limfaticiºi în circulaþia sistemicã, la persoanele sãnãtoase[6, 7].

Pe de altã parte se considerã cã etapele demetastazare urmeazã o succesiune relativ liniarã.(Fig. 2) Celulele desprinse de la nivelul tumoriiprimare migreazã prin þesuturi de obicei de-alungul structurilor anatomice, pãtrund încirculaþia limfaticã ºi sangvinã, apoi extra-vazeazã, iar în noile þesuturi gazdã formeazãmicrometastaze apoi macrometastaze care suntclinic sau imagistic manifeste [6, 8, 9]. Pã-trunderea în circulaþia limfaticã este de obiceiprimul pas pentru diseminarea sistemicã, dar nuneapãrat obligatoriu, diseminarea putându-seproduce ºi direct hematogen [10]. Unii autoriconsiderã cã se poate produce o a doua dise-minare celularã tumoralã de la nivelul macro-metastazelor, însã nu este clar daca acest lucrueste posibil ºi pentru micrometastaze [6, 11].

Este important de subliniat cã nu toatecelulele tumorale extravazate ajung sã formezemetastaze, aºa cum nu toate micrometastazeleprogreseazã spre macrometastaze. Majoritateacelulelor tumorale diseminate nu ajung sãformeze macrometastaze,dimpotrivã. Din acestmotiv,prezenþa celulelor tumorale diseminate încirculaþie nu este un marker fidel al unei viitoaremetastazãri sau a unei metastaze deja consti-tuite[12]. Supravieþuirea celulelor tumorale dise-minate în circulaþia sangvinã, dezvoltarea lor înmicrometastaze ºi ulterior transformarea înmacrometastaze sunt etape limitante în fizio-patologia metastazelor, reprezentând bariere pecare celulele tumorale trebuie sã le depãºeascãpentru ca boala sã intre în etapa de metastazareclinic evidentã. Transformarea micrometastazelorîn macrometastaze este un punct de control deimportanþã particularã, unele micrometastazeputând persista în aceastã fazã indefinit, fãrã aajunge vreodatã la boalã metastaticã clinicmanifestã. Astfel, deºi clinic evidente doar la 10-20% dintre pacienþii cu melanom metastatic,metastazele hepatice sunt prezente la 54-77%

cell dissemination from the primary tumor canoccur early, in situ melanomas, not only in theinvasive stages alone [6] (Fig. 1). This would beconsistent with the inherent high degree ofmobility of normal melanocytes that can befound frequently outside the basal membrane, i.e.in the dermis, lymph nodes and the systemiccirculation, in healthy subjects [6, 7].

On the other hand it is admitted thatmetastasis follows a relatively linear order (Fig. 2). Cells detached from the primary tumormigrate through tissues, usually alonganatomical structures, enter the lymphatic andblood flows, then pass thorough vessel walls andin the new tissues form micrometastases and thenmacrometastases, which manifest clinically orimagistically [6, 8, 9]. The penetration of thelymphatic flow is usually the first step ofsystemic dissemination, but is not mandatory,since dissemination may be directly hematogenic[10]. Some authors consider that second tumorcell dissemination may occur from themacrometastases, but it is unclear if this ispossible for the micrometastases as well [6, 11].

It is important to underscore that not alldisseminated tumor cells end up producingmetastases and not all micrometastasis becomemacrometastases. Conversely, most disseminatedcells do not get to form macrometastases.Therefore, the presence of tumor cellsdisseminated in the blood/lymphatic flows is nota constant marker of a future metastasis or of analready existing one [12]. The survival of thesecells in the blood flow, their development tomicrometastases and ultimately macrometastasesare limiting steps in the pathophysiology ofmetastases [8], and also barriers that tumor cellsmust overcome in order to allow the diseaseprogression to a clinically evident phase.Transformation from micrometastases tomacrometastases is a highly important controlpoint, some metastases may persist in this stageand never arrive to be a clinically obviousmetastatic disease [13]. Moreover, although theyare clinically obvious only in 10-20% of patients

91

DermatoVenerol. (Buc.), 60: 87-108

Moartecelularã

Micrometastaze(supravieþuire)

Extravazare

Proliferare(macrometastaze)

Diseminare secundarã

Stare dormantã

Celulã tumoralã

Vas

san

gvin

Vas

lim

fati

c

Fig. 2. Cãile de metastazare (Adaptat dupã WE Damsky, N.T.a.M.B., Melanoma metastasis: new concepts and evolvingparadigms. Oncogene 2014. 33: p. 2413–2422)

Celldeath

Micrometastases(survival)

Extravasation

Proliferation(macrometastaze)

Dissemination secondary

Dormant state

Cell tumor

Blo

od v

esse

l

Lym

ph

atic

ves

sel

Fig. 2. Metastasis pathways (adapted after WE Damsky, N.T.a.M.B., Melanoma metastasis: new concepts and evolvingparadigms. Oncogene 2014. 33: p. 2413-2422)

92

DermatoVenerol. (Buc.), 60: 87-108

dintre aceºti pacienþi la autopsie [13]. Mai mult,celulele tumorale disemineazã în regiunianatomice unde foarte rar se manifestã clinic,arãtându-se astfel cã boala metastaticã afecteazão proporþie mult mai mare de pacienþi cumelanom decât este evident din punct de vedereclinic [13, 14].

Se considerã cã dupã diseminarea de lanivelul tumorii primare, celulele rãmân într-ostare de dormanþã metastaticã, în care persistãîntr-o stare relativ nonproliferativã[6]. Meca-nismele care dirijeazã starea dormantã ºirespectiv ieºirea din aceasta ºi reluarea profiluluiproliferativ nu sunt înþelese pe deplin, dar existãmai multe ipoteze. Una dintre acestea pleacã dela premisa cã celulele metastatice au o capacitatelimitatã de neoangiogenezã, restricþionându-seastfel dezvoltarea tumoralã [16]. Într-un al doileamodel creºterea tumoralã este constrânsã defactori extrinseci ai tumorii, cum este sistemulimun [17]. O a treia ipotezã presupune cã existã onepotrivire intercelularã sau între celulatumoralã ºi noua matrice, astfel stopându-sedezvoltarea tumoralã în micromediul creat ladistanþã de tumora primarã [15]. Acest concept alcompatibilitãþii dintre celulele tumorale dise-minate ºi micromediul noului þesut gazdã are oimportanþã specialã pentru înþelegerea proce-sului de metastazare, putând explica pre-dispoziþia observatã în practicã a anumitortumori de a disemina predilect în anumite organeºi nu în altele [18].

Conceptul de dormanþã metastaticã acelulelor a condus la dezvoltarea unui model noude reprezentare a procesului de metastazare,acela al progresiei paralele a tumorilor ºimetastazelor. Acest model prevede o mai marediferenþiere între celulele metastatice ºi cele aletumorii primare ºi presupune: continuareaevoluþiei celulelor metastazate în diverse situsuri,cu acumularea de modificãri genetice ºiepigenetice în paralel ºi independent faþã detumora primarã. Aceastã evoluþie continuã arecondiþia ca celulele tumorale diseminate sãdepãºeascã numeroasele obstacole în caleadezvoltãrii la distanþã ºi sã poatã generametastaze relevante clinic [19, 20].

with metastatic melanoma, hepatic metastasesare present in 54-77% of these patients, innecropsy [13]. Moreover, tumor cells disseminateto anatomical regions were they rarely manifestclinically, thus showing that metastatic diseaseaffects a larger portion of melanoma patients thanis clinically obvious [13, 14].

It is admitted that after dissemination fromthe primary tumor, cells remain in a stage calledmetastatic dormancy [15], where they persist in anon-proliferative phase [6]. The mechanisms thatdirect this dormant state, the subsequentreactivation and the relay of the proliferativeprofile are not completely understood, but thereare several hypotheses. The first states thatmetastatic cells are incapable of neoangiogenesisthus limiting tumor development [16]. In asecond model, tumor growth is limited byextrinsic factors, such as the immune system [17].A third hypothesis admits that there is a miss-match between tumor cells and the new matrix,thus limiting tumor development in the tumoralmicroenvironment [15]. This concept of dissemi-nated tumor cells’ compatibility and the micro-environment of the host tissue has a particularimportance in understanding the metastasesprocess in micrometastasis, being able to explainthe propensity of some tumors to disseminatepreferably to some organs and rather than others[18].

The concept of metastatic dormancy of thecells led to the development of a new model ofthe metastatic process, i.e. parallel progression ofprimary tumors and metastases. It anticipates ahigher discrepancy between metastatic andprimary tumor cells [19, 20] and implies: progressof metastatic cells in various sites, withaccumulation of genetic and epigenetic changesparallel and independently from the primarytumor. This continuous evolution admits thatdisseminated tumor cells overcome the manyobstacles for distant development and enablethem to generate clinical relevant metastases [19, 20].

93

DermatoVenerol. (Buc.), 60: 87-108

2. Factori implicaþi în procesul de metastazareîn melanom

Melanomul este o tumorã cu un potenþial demetastazare deosebit de înalt, susþinut decapacitatea de migrare intrinsecã a melanocituluinormal, de constelaþia antigenicã comunã custructurile self vasculare, de capacitatea deneoangiogenezã pentru vase sangvine ºilimfatice, de capacitatea de a influenþa paracrinþesuturile gazdã pentru a stimula propria creºtereprecum ºi de plasticitatea antigenicã, care face caaceastã tumorã, deºi intens imunogenicã, sãeludeze constant sistemului imun al gazdei.

O serie de factori intriseci intervin ºidirecþioneazã aceste abilitãþi ale celulelor demelanom, în diverse etape ale metastazãrii.

Melanomul are un bogat echipament demolecule de adeziune, care intervin în invadareacirculaþiei sangvine ºi limfatice, supravieþuirea înfluxul sangvin, aderarea ºi extravazarea înþesuturi la distanþã [21, 22], dar ºi în supra-vieþuirea celularã ºi rezistenþa la tratament.Constelaþiile particulare de molecule deadeziune, cum ar fi MCAM/MUC18, L1-CAM,ALCAM, NCAM, N-cadherina, VCAM, ICAM,CEA-CAM, PECAM ºi VE-cadherina pot explicametastazarea predilectã a melanomului înanumite þesuturi (piele, ficat, plãmân, creier etc.)

Melanomul are o capacitate crescutã deneoangiogenezã, atât sangvinã cât ºi limfaticã,atât la nivel de tumorã primarã cât ºi demetastaze la distanþã, vasele de neoformaþiesusþinând hrãnirea ºi dezvoltarea tumorii ºiconectarea sa rapidã la sistemul circulator ºidiseminarea. La aceasta contribuie capacitateacelulelor melanomatoase de a produce nu-meroase molecule proinflamatorii ºi pro-angiogenetice cum ar fi ligandul pentru IL-8,VEGFA (vascular endothelial growth factor A),VEGFC, bFGF (basic fibroblast factor), lipidele,PAF (platelet-activating factor) ºi LPA (lipidlysophosphatidic acid) [22-25].

Studii recente au pus în evidenþã capacitateamelanomului de a influenþa þesuturile la distanþã,fãcându-le mai « primitoare » pentru metastaze[22]. În urma transformãrii maligne, celuleletumorale recruteazã celule inflamatorii, stromaleºi imune, supresându-le funcþia citotoxicã ºiinducându-le activitãþi pro-proliferative ºiangiogenetice [26]. Se considerã cã pregãtirea

2. Factors implicated in the metastaticprocess of melanoma

Melanoma is a tumor with a high metastaticpotential, sustained by the inner migration abilityof the normal melanocyte, by the antigenicstructure common to the self vascular structures,by the ability of neoangiogenesis for lymph andblood vessels, by the ability to impact host tissueswith paracrine secretions, in order to stimulatetheir own growth as well as by the antigenicplasticity, which enables this tumor, althoughhighly immunogenic, to constantly evade thehost’s immune system.

There is a series of factors which favor andinfluences melanoma cells’ metastasis in differentstages of metastasis.

Melanoma has a rich equipment of adhesionmolecules, which intervene in the blood andlymph circulation invasion, survival in the bloodflow, adhesion and extravasationto distanttissues [21, 22], but also in cell survival andtreatment resistance. This particular cluster ofadhesion molecules, such as MCAM/MUC18,L1-CAM, ALCAM, NCAM, N-cadherin, VCAM,ICAM, CEA-CAM, PECAM and VE-cadherin areable to explain the predilection of melanoma tometastasizeto particular tissues (skin, liver, lung,brain etc.).

Melanoma has a high neoangiogenesiscapacity, lymphatic as well as haematogenic, inboth the primary tumor and the distancemetastases, the newly formed vessels providingthe necessary nutrition and tumor developmentand its hasty connection to the circulatory systemand, afterwards, dissemination. Contributory tothis are the proinflammatory and proan-giogenetic molecules produced by melanoma-tous cells, such as IL-8 ligand, VEGFA (vascularendothelial growth factor A), VEGFC, bFGF(basic fibroblast factor), lipids, PAF (platelet-activating factor) and LPA (lipid lysophos-phatidic acid) [22-25].

Recent studies have put forth the capacity ofmelanoma to influence remotely located tissues,rendering them more « welcoming » formetastases [22]. After malignant transformation,

94

DermatoVenerol. (Buc.), 60: 87-108

pentru metastazare se realizeazã prin moleculeexcretate în circuitul sangvin de cãtre celulelemelanomatoase, asemãnãtoare modelului exo-toxinelor bacteriene [27]. Aceste molecule suntexportate în mediul extracelular, înglobate înmicrovezicule-exosomi, care le protejeazã înfluxul sangvin ºi au rolul de a pregãti «niºa pre-metastaticã», înainte de migrarea celulelormetastatice propriu-zise. Studii recente [27] aupus în evidenþã rolul exosomilor de originemelanomatoasã în stimularea creºterii matriceiextracelulare în þesuturile gazdã, pregãtireaganglionilor limfatici ºi amorsarea neolim-fangiogenezei, recrutarea de celule derivate dinmãduva hematogenã cu rol adjuvant pentrucreºterea tumoralã [28].

Potenþialul metastazant al melanomului estesusþinut de o serie de mutaþii genetice precum ºide modificarea transcripþiei unor gene cu rol însupravieþuire, migrare ºi proliferare celularã. Înurma cercetãrilor recente, melanomul esteconsiderat a fi cancerul uman cu cea mai înaltãratã de mutaþii genetice. Mutaþiile studiate leinclud pe cele mai frecvente cum ar fi BRAF,NRAS, PTEN, CDKN2A, dar ºi noi mutaþii cu rolde supresori tumorali sau de oncogene, cum ar fiGRIN2A [29], TRRAP [29], MAP3K5 [30],MAP3K9 [30], PREX2 [3], al cãror rol înmetastazare este în curs de elucidare.

În afarã de mutaþiile somatice, creºterea sauscãderea expresiei factorilor de transcripþie cumar fi CREB, AP-2a, ATF2, NFkB ºi MITF(microphtalmia-associated transcription factor)în diverse faze ale diseminãrii tumorale dirijeazãproducþia sau blocarea unui spectru larg demolecule cu rol cheie în tumorigenezã ºimetastazare [35-35].

Melanomul este o tumorã intens imunogenãpe de-o parte, iar pe de alta are capacitatea de ainhiba activitatea sistemului imun al gazdei. Maimult, poate eluda acþiunea sistemului imun prinmultiple mecanisme supresoare, de blocare saude dereglare, ce permit dezvoltarea tumoralã ºiulterior metastazarea. Celula tumoralã poatedepãºi punctele de control ale rãspunsului imunprin exprimarea de CTLA-4 (cytotoxic T-lymphocite antigen 4) ºi a liganzilor receptoruluiPD-1 (programmed cell death receptor) : PD-L 1ºi PD-L2, ducând la scãderea activãrii limfocitelorT ºi respectiv la imunosupresie [36, 37]. Mutaþiile

tumor cells recruit inflammatory, stromal andimmune cells, suppressing their cytotoxicfunction and inducing pro-proliferative andangiogenetic functions [26]. It is considered thatthe preparation for metastasis is accomplishedvia molecules excreted by melanomatous cellsinto the blood system, similar to the bacterialexotoxins model [27]. These molecules areexported into the extracellular environment,covered in microvesicles-exosomes that protectthem from the blood flow and aim to prepare the«pre-metastatic niche», before the metastaticcells’ migration. Recent studies [27] haveunderlined the role of exosomes ofmelanomatous origin in the simulation of theextracellular matrix of host tissues, thepreparation of lymphatic nodes and the inducingof neolymphangiogenesis, recruiting of bonemarrow-derived cells that aid in tumordevelopment [28].

The metastatic potential of melanoma isbacked up by a series of genetic mutations, aswell as by the change in the transcription ofcertain genes implicated in cell survival,migration and proliferation. Following recentstudies, melanoma is considered to be the cancerwith the highest rate of genetic mutations.Mutations studied include the most frequentlyencountered genes like BRAF, NRAS, PTEN,CDKN2A, but also new mutations functioning assuppressor genes or oncogenes, such as GRIN2A[29], TRRAP [29], MAP3K5 [30], MAP3K9 [30],PREX2 [31], whose roles in metastasis are yet tobe elucidated.

Apart from somatic mutations, the increase ordecrease in the expression of transcription factorslike CREB, AP-2a, ATF2, NFkB and MITF(microphtalmia-associated transcription factor)in distinct phases of tumor dissemination guidethe production or inhibition of a large number ofkey-molecules in tumorigenesis and metastasis[32-35].

Melanoma is intensely immunogenic on onehand, and on the other has the capacity todownregulate the immune system of the host.Moreover, it can evade the immune system via

95

DermatoVenerol. (Buc.), 60: 87-108

genetice sau inhibarea componentelor com-plexului major de histocompatibilitate tip 1 secoreleazã cu progresia tumoralã, permiþândcelulei tumorale sã se sustragã acþiuniilimfocitelor T citotoxice CD8+ [38]. În acelaºitimp, celulele dendritice prezentatoare de antigenau rolul de a activa sistemul imun adaptativ prinstimularea limfocitelor T citotoxice antigen-specifice, activitate inhibatã, însã, de supra-stimularea limfocitelor T reglatoare dinmelanom. Supresia sistemului imun se mai poateproduce datoritã secreþiei unor molecule, precumTNF α, TGF β, galectina-3, cu rol angiogenetic ºipro-proliferativ. TGF β în mod particular inhibãactivitatea sistemului imun prin supraactivarealimfocitelor T reglatoare ºi inhibarea celulelordendritice prezentatoare de antigen [40, 41].

3. Cãi de metastazare

Metastazarea în melanom se produce în mareparte, dar nu exclusiv (~80% din cazuri), pe calelimfaticã, prin penetrare de vase limfatice ºineoangiogenezã limfaticã [42]. Creºterea den-sitãþii peritumorale de vase limfatice ºi prezenþade vase limfatice intratumoral sunt markeri aiactivãrii limfangiogenezei tumorale. S-a observatfaptul cã existã o legãturã între densitatea vaselorlimfatice de la nivel tumoral ºi diseminareatumoralã ganglionarã ºi visceralã. Astfel, cu câteste mai mare densitatea vaselor limfatice intra ºiperitumorale, cu atât este mai probabilãpãtrunderea celulelor tumorale în circulaþialimfaticã [42]. Diseminarea secundarã se maipoate produce ºi pe cale hematogenã: celulelemaligne se desprind din tumora primarã,depãºind matricea extracelularã, pãtrund întorentul sanguin ºi se “acoperã” cu trombocite ºileucocite pentru a evita acþiunea forþelor deforfecare din vas ºi a eluda acþiunea sistemuluiimun [43]. Aceastã cale poate explicametastazarea observatã în practicã la nivelvisceral, hepatic sau pulmonar, în absenþametastazãrii obiectivabile la nivelul ganglionilorlimfatici.

În mai micã proporþie, metastazarea se poateproduce ºi prin migrarea extravascularã de-alungul unor structuri anatomice. În cea mai mareparte migrarea se produce de-a lungul nervilor(neurotropism), la nivelul suprafeþelor externeale vaselor sanguine ºi limfatice, de-a lungul

suppressor, blocking and disrupting mechanismsthat allow tumor development and metastasis.The tumor cell can surpass the immune systemcheckpoint by expressing CTLA-4 (cytotoxic T-lymphocite antigen 4) and ligands for PD-1(programmed cell death receptor): PD-L 1 andPD-L 2, which leads to the decrease in activity ofT-lymphocytes, and ultimately to immuno-suppression [36, 37]. Genetic mutations anddownregulation of type 1 major histocompat-ibility complex components correlates withtumor progression, permitting tumor cells toevade CD8+ cytotoxic T-cells [38]. At the sametime, antigen-presenting dendritic cells have therole of activating the adaptive immune systemthrough stimulation of antigen-specific T-cells,role suppressed in melanoma through overstim-ulation of regulatory T cells [39]. A series ofmolecules may also induce immune systemsuppression like TNF α, TGF β, galectina-3,having angiogenetic and pro-proliferative roles.Particularly, TGF β downregulates the immunesystem by means of over activating regulatory Tcells and inhibiting antigen-presenting dendriticcells [40, 41].

3. Metastasis pathways

Metastasis spread in melanoma is producedthrough the lymphatic pathway (~80% of cases),but not solely, by passing through lymph vesselwalls and lymphatic neoangiogenesis [42].Peritumoral aggregation of lymph vessels andintratumoral lymph vessels are markers of tumorlymphatic angiogenesis activation. A connectionwas observed between the density of the tumorallymphatic vessels and the nodal and visceraltumor dissemination. Thus, the higher intra andperitumoral lymph vessel density, the greaterchance of lymphatic penetration and circulationof tumor cells [42]. Secondary dissemination mayoccur hematogenously: malignant cells detachfrom the primary tumor, pass through theextracellular matrix, access the blood flow,“cover” themselves with platelets and leukocytesin order to avoid the shreading forces of thevessels and evade the immune system [43]. This

96

DermatoVenerol. (Buc.), 60: 87-108

anexelor pielii ºi a fasciilor ºi tendoanelor [44].Studiile ultrastructurale au arãtat cã celulelemaligne aderã la suprafeþele externe ale vaselorde-a lungul cãrora migreazã, fãrã a intravaza [45,46]. Mecanismul este aparent stimulat atât deneoangiogenezã cât ºi de neolimfangiogenezã,care cresc suprafaþa disponibilã pentrudiseminare [44].

4. Clasificare ºi prognostic

În funcþie de localizarea ºi distanþa faþã detumora primarã, metastazele cutanate se potclasifica în recurenþe locale, metastaze satelite,metastaze în tranzit sau la distanþã.

Recurenþele locale reprezintã reapariþa uneitumori la nivelul cicatricei post-chirurgicale,dupã o excizie incompletã (din punct de vedereclinic sau histopatologic) a tumorii ºi pentru acestmotiv sunt din ce în ce mai rare. (Fig. 3) În ceea cepriveºte supravieþuirea acestor pacienþi, aceastaeste corespunzãtoare tumorii primare [47].Metastazele satelite sunt cele localizate la <2cmfaþã de tumora primarã. Metastazele în tranzit selocalizeazã la >2cm faþã de tumora primarã, darînainte de bazinul limfatic loco-regional.Conform ultimei stadializãri TNM a mela-nomului, propusã de AJCC în 2009 ºi în vigoare ºiîn prezent, ambele tipuri corespund categorieiN2c în cazul în care nu existã metastazeganglionare sau categoriei N3 în prezenþametastazelor ganglionare. În ceea ce priveºte

can explain the metastasis observed in practice atorgan level, hepatic or pulmonary, in the absenceof objective lymph node metastasis.

To a lower extent, metastasis may beproduced through extravascular migration, alonganatomical structures. Mostly, cells migrate alongnerves (neurotropism), on the external surfaces ofthe lymphatic and blood vessels, along cutaneousadnexal structures, fasces and tendons [44].Ultrastructural studies showed that malignantcells attach themselves to the external surfaces ofthe vessels along which they migrate, withoutpenetrating [45, 46]. The mechanism isapparently stimulated by neoangiogenesis andneolymphangiogenesis, which increase theavailable surface for dissemination [44].

4. Classification and prognosis

According to the location and the distancefrom the primary tumor, skin metastases can beclassified in local recurrences, satellitemetastases, in transit or distant metastases.

Local recurrences feature tumor reap-pearance at the surgical scar site, after anincomplete tumor excision (clinical orhistopathological), thus becoming rare. (Fig. 3)Regarding patient survival, it is related solely tothe primary tumor [47]. Satellite metastases arelocated at <2cm from the primary tumor. Intransit metastases are located at > 2cm from theprimary tumor, but before the loco-regionallymphatic draining station [48]. According to themost recent TNM classification, proposed by theAJCC in 2009, and effective presently, both typescorrespond to the N2c category if there are nolymph nodes metastases or to the N3 category, inthe presence of lymph node metastases.Concerning staging, they rank in stages IIIB (N2c)and IIIC (N2c and N3). Satellite and in transitmetastases associate an unfavorable prognosisequally, the 2 cm limit having no impact onprognosis [48]. According to AJCC 2009, survivalfor N2c at 5 and 10 years is 69%, 52% respectively,and survival for N3 at 5 and 10 years is 46%, 33%respectively [4]. Distant skin metastases arelocated further after the local lymphatic draining

Fig. 3. Recurenþã localã la nivelul unei grefe (Fototecaclinicii de Dermatologie a Spitalului Universitar de

Urgenþã ELIAS)Fig. 3. Local recurrence on a skin graft (Photo library of the

Dermatology clinic of the ELIAS University EmergencyHospital)

97

DermatoVenerol. (Buc.), 60: 87-108

stadializarea, acestea se încadreazã stadiilor IIIB(N2c) ºi IIIC (N2c ºi N3). Metastazele satelite ºicele în tranzit asociazã un prognostic nefavorabilîn aceeaºi mãsurã, limita de 2 cm neavând unimpact asupra prognosticului [48]. ConformAJCC 2009, pentru N2c supravieþuirea la 5 ºi 10ani este de 69%, respectiv 52%, iar pentru N3supravieþuirea la 5 ºi 10 ani este de 46%, respectiv33% [4]. Metastazele cutanate la distanþã selocalizeazã mai departe de bazinul limfatic loco-regional ºi se încadreazã în stadiul IV. Corespundîn clasificarea TNM categoriei M1a dacã con-centraþia plasmaticã a LDH-ului este normalã ºiM1c dacã este crescutã. Pacienþii care se prezintãdoar cu metastaze cutanate la distanþã auprognostic relativ mai bun faþã de cei cumetastaze viscerale (Tabel 1), deºi diferenþastatistic semnificativã nu este suficientã pentruîncadrarea în clase prognostice diferite, rata desupravieþuire rãmânând redusã la aproximativ30% la 5 ani, iar la 10 ani < 20% [4].

5. Aspecte clinice, diagnostic diferenþial ºievoluþie

Metastazele cutanate ale melanomului se potlocaliza la nivelul oricãrei regiuni anatomice, însãcu precãdere la nivelul toracelui posterior labãrbaþi ºi membrelor inferioare la femei, aspectexplicat de faptul cã aproximativ 30% dintredeterminãrile secundare cutanate se localizeazãîn apropierea tumorii primare (Fig. 4, Fig. 5) [49].Caracteristicile clinice ale leziunilor sunt extremde variate: de la papule, noduli unici sau multiplipânã la placarde. Culoarea poate varia, astfelîncât leziunile pot fi eritematoase, roºietice,brune, negre, amelanotice sau pot avea culoareapielii. Uneori, deºi tumora primarã a fostpigmentatã, metastazele sale pot fi amelanotice ºiinvers. Metastazele sunt de obicei mobile faþã de

station and fall in stage IV. They rank in the M1acategory in the TNM classification if theplasmatic LDH concentration is normal and M1cif it is increased. Patients presenting only withdistant skin metastases have a better prognosisthan the ones with organ metastases (Table 1),although the difference is not statisticallysignificant, it is not enough for ranging indifferent prognosis classes, survival rateremaining low at approximately 30% at 5 years,and at 10 years < 20% [4].

5. Clinical aspects, differential diagnosisand evolution

Melanoma skin metastases can be located atany anatomic region, although the posterioraspect of the trunk in men and legs in women arepredilect, since 30% of secondary skindeterminations are located near the primarytumor (Fig. 4, Fig. 5) [49]. Clinical features areextremely variable: from papules, solitary ormultiple nodules to plaques. The color may vary,lesions can be erythematous, reddish, brown,black, amelanotic or skin color. Sometimes,although the primary tumor was pigmented, itsmetastases may be amelanotic and vice-versa.Metastases are usually mobile on the lowerplanes, hard consistency, tending to ulcerate.(Fig. 6)

Other more rare aspects are erythematousplaques, inflammatory erysipeloid lesions,sclerodermoid lesions (“en cuirasse” metastases),telangiectatic papulo-vesicles, purpuric plaquesthat mimic vasculitis and neoplastic alopecia.Even more rare are the zosteriform metastaseswhich consist of vesiculo-bulae with herpetiform

Tabel 1. Supravieþuirea la 1, 5 ºi 10 ani a pacienþilor cumetastaze cutanate vs. metastaze viscerale conform AJCC2009 . M1a-metastaze cutanate la distanþã; M1b-metastazepulmonare; M1c-alte metastaze viscerale cu LDH normal

sau orice metastazã la distanþã cu LDH crescut.

Categorie M1a M1b M1c

Supravieþuire

1 an 62% 53% 33%

5 ani ~28% ~18% 10%

10 ani 20% ~10% <10%

Table 1. Patients’ survival at 1, 5 and 10 years, with skin vsorgan metastasis, according to AJCC 2009 . M1a-distant

skin metastases; M1b-pulmonary metastases; M1c- otherorgan metastases with normal LDH or any other distant

metastasis with increased LDH.

Category M1a M1b M1c

Survival

1 year 62% 53% 33%

5 years ~28% ~18% 10%

10 years 20% ~10% <10%

98

DermatoVenerol. (Buc.), 60: 87-108

planurile subiacente, de consistenþã durã, cutendinþã la ulcerare. (Fig. 6)

Alte aspecte clinice mai puþin întâlnite suntplãcile eritematoase, leziuni inflamatoriierizipelatoide, leziuni sclerodermoide (metastaze“en cuirasse”), papulo-vezicule telangiectazice,plãci purpurice ce mimeazã vasculita ºi alopecianeoplazicã. Încã ºi mai rare sunt metastazelezosteriforme ce constau în veziculo-bule cuaspect herpetiform sau papule ºi noduli cu

appearance or papules and ranging along one ormore dermatomes. In these cases clinicaldiagnosis may be challenging because metastasescan mimic benign lesions [47].

Melanoma skin metastases are notsymptomatic, although sometimes patients mayhave paresthesias or local pain, as a result ofedema and tissular mechanical compression [47].Musculo-nervous infiltration results in painfullesions, symptoms that are relatively difficult tocontrol. Regarding local complications, mostfrequently encountered are local bleeding andinfection, which may significantly affect thepatient’s quality of life.

Differential diagnosis includes numerousbenign and malignant entities (Table 2). In 2-8%of melanoma patients, skin metastases may bethe first form of clinical manifestation [50]. Inthese cases, the differential diagnosis is evenmore challenging. Among malignant lesions, themost important are the metastases of othermalignant diseases and primary melanomas.Benign lesions which frequently mimic cutane-ous metastases are: benign melanocytic lesions,blue nevus, hemangiomas and dermatofibroma.

Savoia et. al observed that the mean durationfrom a primary melanoma diagnosis to local anddistant metastases occurrence is 1.3 andrespectively 2.9 years [49]. Another observation

Fig. 4. Metastazã în tranzit-sãgeata neagrã; Cicatrice post-excizionalã melanom primar- sãgeatã albã (Fototeca clinicii

de Dermatologie a Spitalului Universitar de UrgenþãELIAS)

Fig. 4. In transit metastasis - black arrow; Post-excisionalscar of a primary melanoma-white arrow

(Photo library of the Dermatology clinic of the ELIASUniversity Emergency Hospital)

Fig. 6. Metastaze cutanate sub formã de noduli multipli,bruni, ulceraþi la nivelul hemiabdomenului drept(Fototeca clinicii de Dermatologie a Spitalului Universitar

de Urgenþã ELIAS)Fig. 6. Skin metastases: brown, ulcerated nodular lesions

on the right hemiabdomen (Photo library of the Dermatology clinic of the ELIAS

University Emergency Hospital)

Fig. 5. Metastaze în tranzit (Fototeca clinicii deDermatologie a Spitalului Universitar de Urgenþã ELIAS)

Fig. 5. In transit metastases (Photo library of theDermatology clinic of the ELIAS University Emergency

Hospital)

99

DermatoVenerol. (Buc.), 60: 87-108

distribuþie la nivelul unuia sau mai multordermatoame. În aceste cazuri, diagnosticul clinicpoate fi o provocare pentru cã metastazele potmima afecþiuni benigne [47]. Metastazelecutanate ale melanomului sunt în marea lormajoritate asimptomatice, deºi uneori pacienþiipot avea parestezii sau durere localã datoritãedemului ºi compresiunii mecanice la niveltisular [47]. În momentul infiltrãrii musculo-nervoase leziunile devin dureroase, simpto-matologie relativ greu de controlat. În ceea cepriveºte complicaþiile locale, cel mai frecventîntâlnite sunt sângerarea ºi suprainfecþia ce potafecta semnificativ calitatea vieþii pacientului.

Diagnosticul diferenþial include numeroaseentitãþi benigne ºi maligne (Tabel 2). La 2-8%dintre pacienþii cu melanom, metastazelecutanate pot fi prima manifestare clinicã [50]. Înaceste cazuri, diagnosticul diferenþial este cu atâtmai provocator. Dintre afecþiunile maligne, celemai importante de reþinut sunt metastaze alealtor neoplazii ºi melanoamele primare.Afecþiunile benigne care mimeazã frecventmetastaze cutanate sunt: leziunile melanocitarebenigne, nevul albastru, hemangioamele ºidermatofibromul.

Savoia et. al au observat faptul cã duratamedie de la diagnosticul unui melanom primarpânã la apariþia metastazelor cutanatelocoregionale ºi la distanþã este de 1,3 ºi respectiv2,9 ani [49]. O altã observaþie a fost cã la 50%dintre pacienþi pielea este regiunea predilectãpentru metastazarea melanomului, iar la 56%dintre aceºtia metastazarea cutanatã reprezintãprimul semn al progresiei tumorale. Aproximativ10% dintre pacienþi prezintã concomitentmetastaze la distanþã, nodale ºi viscerale ºi foarterar (3% din cazuri) dezvoltã metastaze cutanate

was that in 50% of the patients skin was thepreferred site for melanoma metastases, and thatin 56% of them skin metastases represents thefirst sign of tumor progression. Approximately10% of the patients have simultaneous distantmetastases, nodal and visceral and very rarely(3% of the cases) develop skin metastases afterorgan dissemination [49]. Of note is the fact thatsatellite or in transit skin metastases occurrelatively early in disease evolution, but have aslower progression until visceral metastases.Vice-versa, in patients who develop distantmetastases, the disease-free duration until lesionoccurrence is longer, but time to organdissemination shortens [47].

6. Dermatoscopic diagnosis

Melanoma skin metastases do not have apathognomonic dermatoscopic aspect, but ratherseveral particular models are found in certain benignor malignant lesions, to a variable extent [50-52].

The homogenous pattern consists of a diffusepigmentation, without any other structures,either red, brown or blue. The brownhomogenous aspect may mimic an atypicalnevus. This aspect may also be encountered in ablue nevus, melanoma or hemangioma [50].

The saccular pattern is specific to malignantlesions, but may be encountered in basal cellcarcinomas, hemangiomas and Clark nevi aswell. The saccular aspect is the result of oval nestsof atypical melanocytes, at the dermo-epidermicjunction. It also has color variations which showthe degree of neoangiogenesis and the quantity ofmelanin pigment produced by the atypical cellsinvading the epidermic layers chaotically.

Tabel 2. Diagnosticul diferenþial al metastazelor cutanateale melanomului [2, 50, 53]

Formaþiuni benigne Formaþiuni maligne

Leziuni melanocitare benigne Metastaze ale altor neoplaziiNev displazic Melanom primarHemangiom AngiosarcomNev albastru LeiomiosarcomDermatofibrom Carcinom bazocelularHerpes zoster Fibroxanthomul atipicAlopecia areata Limfoame

Table 2. Differential diagnosis melanoma skin metastases[2, 50,53]

Benign lesions Malignant lesions

Benign melanocytic lesions Metastases of other malignant diseases

Dysplastic nevus Primary melanomaHemangioma AngiosarcomaBlue nevus LeiomiosarcomaDermatofibroma Basal cell carcinomaHerpes zoster Atypical fibroxanthomaAlopecia areata Lymphomas

100

DermatoVenerol. (Buc.), 60: 87-108

dupã diseminarea visceralã [49]. De remarcat estefaptul cã metastazele cutanate satelite sau întranzit apar relativ precoce în evoluþia bolii, darau o progresie mai lentã pânã la apariþia metas-tazelor viscerale. Invers, în cazul pacienþilor caredezvoltã întâi metastaze la distanþã, durata liberãde boalã pânã la apariþia acestora este mai lungã,însã se scurteazã durata de timp pânã ladiseminarea visceralã [47].

6. Diagnostic dermatoscopicMetastazele cutanate ale melanomului nu au

un aspect dermatoscopic patognomonic, ci maimult anumite modele care se regãsesc ºi înanumite leziuni benigne sau maligne în diverseproporþii [50-52].

Modelul omogen se caracterizeazã prinpigmentare difuzã, fãrã alte structuri, de culoareroºie, brunã sau albastrã. Aspectul brun omogenpoate mima un nev atipic. Acest aspect poate fiîntâlnit ºi la nevul albastru, melanom sauhemangiom [50].

Modelul sacular este un aspect relativ specificleziunilor maligne, dar poate fi întâlnit ºi încarcinomul bazocelular, hemangioame ºi neviClark. Aspectul sacular se datoreazã cuiburilorovalare de melanocite atipice de la niveluljoncþiunii dermo-epidermice. Prezintã, deasemenea, variaþii de culoare care reprezintãnivelul de neoangiogenezã ºi cantitãþii depigment melanic produs de celulele atipice careinvadeazã straturile epidermice în mod haotic.Hemangioamele pun frecvent probleme dediagnostic diferenþial din cauza lacunelorvasculare similare aspectului sacular, ambeleavând culoare uniformã ºi margini binedelimitate. Alte leziuni care pot avea acest aspectdermatoscopic sunt nevul albastru ºi carcinomulbazocelular [50, 51].

Modelul amelanotic este întâlnit la 32%dintre metastazele cutanate ale melanomului. Nuprezintã caracteristici dermatoscopice remar-cabile din cauza localizãrii dermale a leziunii ºiabsenþei pigmentului. Prezintã vase serpiginoase,cu aspect de ac de pãr, tirbuºon, arborizate,punctate ºi zone alb-lãptoase. Uneori se potobserva ºi lacune vasculare, slab delimitate, cuvase în ac de pãr ºi serpiginoase. Diagnosticuldiferenþial se poate face cu melanomul ºi nevulalbastru [50, 52].

Modelul vascular este cel mai frecventîntâlnit la metastazele cutanate ale melanomului(53%). Caracteristicile prezente în acest modelsunt corelate cu grosimea tumoralã. Astfel, vasele

Hemangiomas frequently pose differentialdiagnosis problems as a result of vascularlacunae similar to the saccular aspect, bothhaving a uniform color and well defined margins.Other lesions that can have the samedermatoscopic aspect are the blue nevus andbasal cell carcinoma [50, 52].

The amelanotic pattern is encountered in 32%of cutaneous metastases. It does not haveremarkable dermatoscopic characteristicsbecause of the dermal localization and theabsence of pigment. It has serpiginous, hair pin,,branching and dotted vessels and milky-whiteareas. Sometimes, poorly delimited vascularlacunae, with hair pin and serpiginous vesselsmay be observed. The differential diagnosisincludes melanoma and blue nevus [51, 52].

The vascular pattern is the most frequentlyencountered in melanoma skin metastases (53%).The characteristics of this model are correlatedwith tumor thickness. Thus, dotted vesselscorrespond to thin tumors, whereas corks crewvessels correspond to the thick tumors.Corkscrew vessels are characteristic for themelanoma skin metastases (83%). This pattern ismore often seen in metastases rather thanprimary melanomas because of neoangiogenesistypical to tumoral progression and disse-mination. A clue to differentiating primarymelanomas from melanoma metastases, from avascular point of view, is that vessels are locatedat the center of the primary tumor, whereas inmetastases they are located peripherally. Thedifferential diagnosis includes hemangiomas,primary melanomas and blue nevi.

The polymorphic pattern encompassesvarious dermatoscopic structures with anirregular arrangement; this aspect is also presentin other benign or malignant lesions, likepyogenic granuloma and melanoma [50].

Other aspects that may indicate the presenceof a skin metastasis are a reddish color suggestingneoangiogenesis, peripheral grey globules, whichare the result of melanin particles from themelanophages, or distributed at in the dermis,more rarely perilesional erythema, resulted from

101

DermatoVenerol. (Buc.), 60: 87-108

punctate sunt corespunzãtoare tumorilor subþiri,iar cele cu aspect de tirbuºon, tumorilor groase.Vasele cu aspect de tirbuºon sunt caracteristicemetastazelor cutanate ale melanomului (83%).Este un aspect mult mai întâlnit în metastazelecutanate decât în melanoamele primare prinprisma neoangiogenezei tipice progresiei ºidiseminãrii tumorale. Un indiciu pentru adiferenþia din punctul de vedere al vascularizaþieimelanoamele primare de metastazele cutanateeste faptul cã în tumorile primare vasele suntdispuse în principal central, iar în metastazevasele sunt dispuse periferic. Diagnosticuldiferenþial include hemangioamele, melanoameleprimare, nevii albaºtri [5, 51].

În modelul polimorf structurile derma-toscopice variate sunt dispuse neregulat, aspectprezent ºi în alte leziuni benigne sau maligne,cum ar fi granulomul piogen ºi melanomul [50].

Alte aspecte care ar putea indica diagnosticulde metastazã sunt culoarea roºiaticã, cesugereazã neoangiogeneza, globulii gri periferici,datoraþi particulelor de melaninã din melanofagesau distribuite la nivelul dermului, eritemulperilezional, întâlnit mai rar ºi datoratvascularizaþiei polimorfe, ºi haloul pigmentar(40% din cazuri) dispus asimetric [50].

7. Diagnostic histopatologic ºiimunohistochimic

Examenul histopatologic urmãreºte înprincipal diferenþierea metastazelor cutanate deun melanom primar, în majoritatea cazurilor, saude un nev albastru, un carcinom bazocelular sauun hemangiom, precum ºi de metastazelecutanate ale altor neoplazii. Metastazele cutanateale melanomului au câteva caracteristici-cheiecare le diferenþiazã de melanoamele primare: nuprezintã epidermotropism sau acesta este limitatla straturile imediat supraiacente, nu prezintãreacþie inflamatorie, iar epidermul periferic estede obicei hiperplazic [53]. De asemenea, un altindiciu este faptul cã metastazele cutanate selocalizeazã la nivel dermic sau subcutanat, cumarcatã invazie limfaticã ºi angiotropism. Nuprezintã zone de regresie ºi foarte rar selocalizeazã în preajma unui nev [53]. Uneorimetastaza cutanatã poate mima ºi histopatologicun nev albastru, ceea ce poate face diagnosticulfoarte dificil. Spre deosebire de acesta, metastazacutanatã prezintã însã melanocite atipice îndermul reticular, melanofage, atipii nucleare,mitoze ºi un aspect general de pleomorfismstructural [54, 55].

polymorphic vascularization and pigmentedhalo (40% of the cases) placed asymmetrically[50].

7. Histopathological andimmunohistochemical diagnosis

The histopathological exam aims mainly todifferentiate the skin metastases from a primarymelanoma or from a blue nevus, a basal cellcarcinoma or a hemangioma, as well as from skinmetastases of other malignant diseases. Skinmetastases have a few key aspects whichdistinguish them from primary melanomas: theylack epidermotropism, or if present, it is limitedto the immediately overimposed layers,lackinflammatory reaction and the peripheralepidermis is usually hyperplasic [53]. Anothersign is the fact that skin metastases be located inthe dermis or subcutaneous tissue, with markedlymphatic invasion andangiotropism. They donot have regression areas and are very rarelylocated to close to a nevus [53]. Sometimes skinmetastases may histopathologically mimic a bluenevus which renders the diagnosis very difficult.Unlike the blue nevus, skin metastases haveatypical melanocytes in the reticular dermis,melanophages, atypical nuclei, mitoses and ageneral pleomorphic aspect [54, 55].

As a result of a difficult histopathologicaldiagnosis, immunohistochemistry can be used,especially in the cases in which the primarytumor is unknown. Immunohistochemistry aimsto confirm the melanocytic nature of a lesion onone side, and on the other to discern skinmetastasis from a primary melanoma. Con-firmation of the melanocytic nature is done bymarkers S100, Melan-A/MART-1 (melanomaantigen recognized by T cells 1) and HMB-45(Human melanoma black-45) [56]. One of thedifferences between the primary melanoma andskin metastasesis the fact that ultimately theymay lose their marker C117/c-kit (encountered innormal melanocytes, melanocytic nevi, in situmelanomas and in the radial growth phase ofmelanomas being present in only 4% ofmelanoma skin metastases [54]. Mutant p53protein (tumor suppression protein) is

102

DermatoVenerol. (Buc.), 60: 87-108

În cazul dificultãþilor de diagnostic histo-patologic se poate apela la imunohistochimie,mai ales în cazurile în care nu se cunoaºte tumoraprimarã. Scopul imunohistochimiei este de aconfirma natura melanocitarã a leziunii, pe de-oparte, iar pe de alta de a diferenþia metastazacutanatã de un melanom primar. Confirmareanaturii melanocitare se face cu ajutorulmarkerilor S100, Melan-A/MART-1 (melanomaantigen recognized by T cells 1) ºi HMB-45(Human melanoma black-45) [56]. Una dintrediferenþele imunohistochimice dintre melanomulprimar ºi metastazele cutanate este faptul cã celedin urmã îºi pot pierde markerul C117/c-kit(întâlnit la melanocitele normale, nevii melano-citari, melanoamele in situ ºi melanoamele în fazade creºtere radialã), acesta fiind prezent doar la4% dintre metastazele cutanate ale melanomului.Proteina p53 (proteinã de supresie tumoralã)mutantã este întâlnitã frecvent în melanoameleaflate în faza de creºtere verticalã, respectiv cândcelulele tumorale au cãpãtat potenþial metastatic,ºi în metastazele cutanate (54%) ºi foarte rar înfaza de creºtere radialã (9%) [54]. Un alt markerpentru proliferare este PCNA (proliferating cellnuclear antigen), cofactor prezent în toate fazelede diviziune celularã. Este prezent deopotrivã îndeterminãrile secundare (89%), dar ºi într-oproporþie mare în tumorile primare (50%) [54].

8. Principii de tratamentAlegerea modalitãþii de tratament depinde de

numeroºi factori: localizarea, numãrul leziunilor,prezenþa afectãrii sistemice, vârsta pacientului ºicomorbiditãþile acestuia. Diferenþele deprognostic dintre pacienþii cu afectare loco-regionalã ºi cei cu metastaze la distanþã justificãabordãrile terapeutice diferite. În cazurile în caremetastazele cutanate sunt singura manifestare abolii, tratamentul lor are rol curativ. În celelaltecazuri, principalele obiective ale tratamentuluimetastazelor cutanate sunt paliaþia, mai alespentru leziunile care produc impotenþãfuncþionalã, prevenþia complicaþiilor locale casângerarea, distrugerea localã tisularã sausuprainfecþia, ºi pentru îmbunãtãþirea aspectuluicosmetic ºi a calitãþii vieþii [47].

Tratamentul chirurgical rãmâne standardulde aur ºi totodatã tratamentul cel mai eficientpentru afectarea limitatã, respectiv leziuni demici dimensiuni, grupate pe o suprafaþã de micidimensiuni. Excizia se produce macroscopic, fãrãa necesita margini de siguranþã corespunzãtoaregrosimii tumorale [47, 57]. Are un nivel demorbiditate acceptabil. Sunt preferabile sutura

encountered in melanomas in the vertical growthphase, i.e. when the tumor cells has metastaticpotential, and in skin metastases (54%) andseldom in the radial growth phase (9%) [54].Another proliferation marker is PCNA(proliferating cell nuclear antigen), a cofactorpresent in all division cell phases. It is present insecondary determinations (89%), as well as inprimary tumors, in a high proportion (50%) [54].

8. Treatment options

Treatment choice depends on numerousfactors: location, number of lesions, systemicinvolvement, patient age and comorbidities.Prognosis differences between patients with localand regional involvement and those with distantmetastases explain different therapeuticapproaches. In the cases in which skin metastasesare the only manifestation of the disease,treatment has a curative role. In other cases,treatment mainly aims palliation, especially forthe lesions which produce functionalimpairment, complications like bleeding, localtissue destruction or infection, and cosmetic andquality of life improvement [47].

Surgical treatment remains the gold standardand there with most effective for the limitedimpairment, i. e. small lesions, grouped on asmall surface. The excision is done macroscop-ically, with no need of security marginscorresponding to tumor thickness [47, 57]. It hasan acceptable morbidity level. Direct suture andgraft are preferred, because local reconstructionwith flap alters the local lymphatic flow. Theamputation may be taken into account only incase of high intensity pain, ulcerative andnecrotic lesions and important bleeding [57].

Isolated limb perfusion (ILP) or infusion (ILI)[58] are two options useful in lesions located onan extremity and that cannot be surgicallyremoved. The patient is submitted to anextracorporeal circulation on the affectedextremity (with or without mild hyperthermia),followed with the administration of a cytotoxicagent for 30 (ILI) or 60 minutes (ILP). Theextracorporeal circulation allows for the

103

DermatoVenerol. (Buc.), 60: 87-108

directã ºi grefa, deoarece reconstrucþia localã culambou modificã circulaþia limfaticã localã.Amputaþia se poate lua în calcul doar în cazulleziunilor cu dureri de mare intensitate, ulcero-necrotice sau cu sângerãri mari cantitativ [57].

Perfuzia (ILP-isolated limb perfusion) sauinfuzia (ILI-isolated limb infusion) [58]extremitãþii izolate sunt douã opþiuni terapeuticeutile pentru metastazele localizate la nivelul uneiextremitãþi care nu pot fi rezecate chirurgical. Serealizeazã o circulaþie extracorporealã la nivelulextremitãþii afectate (cu sau fãrã hipertermielocalã uºoarã), urmatã de administrarea unuiagent citotoxic timp de 30 (ILI) sau 60 minute(ILP). Circulaþia extracorporealã permiteadministrarea de doze de agenþi citotoxici chiar ºide 10 ori mai mari faþã de doza sistemicãtolerabilã. Cel mai frecvent agent citotoxic utilizateste melphalanul cu sau fãrã administrare deTNF alpha. Rolul TNF alpha este de a afectamicrovascularizaþia tumoralã, ducând laischemie. Hipertermia (39-41oC pentru ILP ºi 37-40oC pentru ILI) produce vasodilataþie ºi creºteefectul citotoxic al agenþilor folosiþi. Dozele demelphalan utilizate sunt 10 mg/L volum pentrumembrele inferioare ºi 13 mg/L volum pentrumembrele superioare. Alþi agenþi citotoxicifolosiþi sunt dacarbazina ºi dactinomicina. ILPnecesitã anestezie generalã, însã ILI este utilizatãcu anestezie localã. Efectele secundare cutanatepot varia de la eritem uºor pânã la inflamaþiaþesuturilor profunde, neuropatie, durere ºi edem.Efectele sistemice întâlnite sunt greaþa,vãrsãturile ºi supresia medularã uºoarã, dar suntrelativ rare. Aceste metode nu prelungescsperanþa de viaþã. Vârsta nu reprezintã ocontraindicaþie pentru aceste terapii. Ratageneralã de rãspuns terapeutic este de 84%pentru ILI ºi pânã la 90% pentru ILP. ILI nu areaceeaºi eficacitate ca ºi ILP, însã este mai binetoleratã ºi se asociazã cu o morbiditate maiscãzutã faþã de ILP [62].

Electrochimioterapia este o metodã dezvol-tatã recent, prin care, sub anestezie localã sausedare uºoarã, se administreazã intravenosbleomicinã sau cisplatinã [63], urmatã deaplicarea de impulsuri electrice la nivel tumoral,în momentul în care concentraþia tisularã aagenþilor citotoxici este maximã. Rolulimpulsurilor electrice este de a permeabilizamembrana celulei tumorale ºi a permitepãtrunderea macromoleculelor cito-toxice. Aretoxicitate sistemicã minimã ºi este bine toleratãde pacienþii cu comorbiditãþi importante. Areavantajul cã poate fi utilizatã atât pe metastaze

administration of cytotoxic agents in as high as 10times the tolerable systemic dose. Most oftenmelphalan is used with or without TNF alpha.The role of TNF alpha is to affect tumoralmicrovascularization, leading to ischemia [59].Hyperthermia (39-41oC for ILP and 37-40oC forILI) leads to vasodilatation and increases thecytotoxic effect of the used agents[47, 57, 60, 61] .Melphalan doses used are 10mg/L volume forthe lower limbs and 13 mg/L volume for theupper limbs. Other cytotoxic agents used aredacarbazin and dactinomycin. ILP requiresgeneral anesthesia, whereas ILI only requireslocal anesthesia. Secondary side-effects may varyfrom mild erythema to deep tissue inflammation,neuropathy, pain and edema. Systemic side-effects include nausea, vomiting and mildmedular suppression, but are rather rare. Thesetherapies do not prolong lengthen lifeexpectancy. Age is not a restriction for thesetherapies. The general response rate for ILI is 84%and 90% for ILP [47, 57, 61]. ILI does not have thesame efficacy as ILP, but better tolerated and hasa lower morbidity rate than ILP [62].

Electrochemotherapy is a recently developedmethod [59], where, under local anesthesia ormild sedation, patients receive bleomycin orcisplatin intravenously [63], followed by theapplication of electric impulses at the tumorlevel, when cytotoxic agents’ level reach amaximum concentration. The role of electricimpulses is to increase cell membranepermeability and to allow the cytotoxicmacromolecules to enter the cell. It has aminimum systemic toxicity and is well toleratedby patients with important comorbidities. It alsohas the advantage that it can be used on newmetastases, as well as older lesions with partialremission. Secondary side-effects are localerythema and edema, superficial erosions andscars [64]. It has a 53-89% response rate [47].

Other possible therapeutic options are lasertherapies. Pulse Dye Laser (PDL) with or withoutImiquimod leads to the photocoagulation oftumor vessels. Imiquimod increases the local

104

DermatoVenerol. (Buc.), 60: 87-108

noi, cât ºi pe leziuni mai vechi, cu remisiuneparþialã. Efectele secundare ale acestei terapiisunt eritemul ºi edemul local, eroziunilesuperficiale ºi cicatricele [64]. Are o ratã derãspuns terapeutic de 53-89% [47].

Alte variante posibile sunt terapiile laser.Laserul PDL (Pulse Dye Laser) cu sau fãrãadministrare de Imiquimod, produce o foto-coagulare a vascularizaþiei tumorale. Imiqui-modul are rolul de a creºte rãspunsul inflamatorlocal produs de PDL ºi imunitatea antitumoralã.Creºte semnificativ calitatea vieþii, mai ales încazul leziunilor extinse, sângerânde. Laserul CO2este util leziunilor de dimensiuni mici < 2 cm,superficiale. Este o terapie minim invazivã, fãrãca defectul rezultat sã necesite o intervenþiechirurgicalã [47, 66, 67].

Crioterapia este o tehnicã trecutã în plansecund dupã introducerea ablaþiei laser ºi aelectrochimioterapiei. Se utilizeazã spray cu azot(-50- -60oC) în vederea distrugerii tisularedirecte[47] .

Radioterapia este rezervatã paliaþiei. Esteutilizatã pentru leziunile simptomatice, incu-rabile, care nu pot fi controlate chirurgical. Unelestudii au arãtat o duratã mai lungã a perioadeilibere de boalã ºi creºterea supravieþuirii lapacienþii radiotrataþi, deºi rata de rãspunscomplet este micã, iar radioterapia nu previneapariþia metastazelor la distanþã, [57, 68].

Dintre terapiile intralezionale, în trecut a fostutilizatã injectarea BCG (bacilul Calmette-Guérin) la nivel lezional, având scopul de ainduce un rãspuns imun sistemic. A fostintrodusã de Morton ºi colegii în 1974, cândstudiul publicat de aceºtia a arãtat o regresie a90% dintre leziunile injectate, dar ºi o regresiespontanã a 17% dintre leziunile martor. Dincauza infecþiilor sistemice, a reacþiilor cutanate ºianafilaxiilor este folosit astãzi foarte rar[2][47].Interleukina 2 este acceptatã ca terapieintralezionalã, cu un nivel de toxicitate mai bundecât BCG-ul. Pot fi întâlnite reacþii cutanateadverse, dar efectele secundare sistemice suntminime. Este o terapie costisitoare, consumatoarede timp, necesitând multiple administrãrisãptãmânale pentru rezultate favorabile. Nuproduce rãspuns imun sistemic [57]. Altevariante terapeutice în urma cãrora se obþinrezultate locale bune sunt: Interferonul gamma ºialpha ºi diphenciprona, fãrã a produce rãspunsimun sistemic. Talimogene Laherparepvec (T-vec) este un virus herpes simplex modificatpentru a se replica selectiv în celulele tumorale,stimulând ºi producþia de GM-CSF. Terapia

inflammatory response produced by PDL and theantitumoral immunity. It significantly increasesquality of life, especially in bleeding extensivelesions [65]. The CO2 laser can be used forsuperficial lesions, smaller than 2 cm. It is aminimally invasive therapy that doesn’t require asurgical intervention [47, 66, 67].

Cryotherapy has become a second-linetreatment after the introduction of laser ablationand electrochemotherapy. This techniquerequires the use of nitrogen spray (-50- -60oC) fordirect local tissue distruction [47].

Radiotherapy is reserved for palliation. It isused for incurable, symptomatic lesions thatcannot be controlled surgically. Some studieshave showed a longer disease-free period and anincrease in patient survival in patients whoreceived radiotherapy, although the response rateis low, and radiotherapy does not prevent distantmetastases development [57, 68].

Among intralesional therapies, intralesionalBCG (Calmette-Guérin bacillus) injections wereused, aiming at increasing the immune responserate. It was first introduced by Morton et. al. in1974, when their study showed a 90% regressionof injected lesion, and also a spontaneousregression of 17% of control lesions. Because ofsystemic infections, cutaneous reactions andanaphylaxis it is rarely used today [2, 47].Interleukin-2 is widely accepted as anintralesional therapy, with a better toxicity profilethan BCG. However, it is rather expensive, time-consuming, and requires multiple weeklyadministrations for favorable results. It does notproduce a systemic response [57]. Other optionswith good local results are gamma and alphainterferon and diphenciprone, withoutproducing a systemic response. TalimogeneLaherparepvec (T-vec) is an injectable herpessimplex virus, modified in order to selectivelyreplicate in tumor cells, also stimmulating GM-CSF production. Intralesional therapy with T-vecleads to tumoral regression of injected lesions,but also of control lesion, probably generating asystemic antitumoral immune response. It wasstudied in phase II and III trials, phase II showinga tumoral regression maintenance between 7 and31 months. Side-effects are flu-like symptoms(fever, chills and fatigue) [57]. PV-10/Rose Bengal

105

DermatoVenerol. (Buc.), 60: 87-108

intralezionalã cu T-vec poate produce regresietumoralã a leziunilor injectate, dar ºi a unoradintre leziunile la distanþã, posibil prin generareaunui rãspuns imun antitumoral sistemic. A foststudiat în trialuri de fazã II ºi III, observându-seîn faza II o menþinere a regresiei tumoralecuprinsã între 7 ºi 31 de luni. Reacþiile adverseînregistrate sunt pseudo-gripale (febrã, frison ºifatigabilitate) [57]. PV-10/Rose Bengal a fostutilizat de mult timp pentru evaluarea funcþieihepatice. Este studiat ca o soluþie injectabilã 10%pentru metastazele melanomului, cu scopulobþinerii unui rãspuns antitumoral sistemic,aflându-se în momentul de faþã în trialuri de fazãIII. În trialurile de fazã I ºi II s-a observat oregresie tumoralã pe termen lung, cu toxicitatesistemicã minimã [47, 57].

Terapiile sistemice pot fi folosite la pacienþiicare nu au rãspuns sau nu au fost eligibili pentrutratamentele locale (cu afectare cutanatã extinsã).Terapiile disponibile astãzi includ terapia þintitãcu inhibitori ai MAP Kinazelor la melanoamelecu mutaþii ale BRAF (Vemurafenib, Dabrafenib,Trametinib) [69, 70] ºi imunoterapia adresatãmoleculelor cu rol de check-point al rãspunsuluiimun cum ar fi CTL4 (Ipilimumab) [71], PD1 ºiPD1-L (Nivolumab, Pembrolizumab) [72, 73].Acestea pot fi utilizate în funcþie decaracteristicile fiecãrui pacient, la cei cu boalãmetastaticã progresivã, neresponsivã la celelalteterapii loco-regionale sau ca terapii de primã linieîn cazul coexistenþei de metastaze viscerale.

Concluzii

Metastazele cutanate ale melanomului suntun fenomen întâlnit frecvent în istoria naturalã abolii, cu un prognostic mai bun decât cel almetastazelor viscerale. Diagnosticul lor precocepoate îmbunãtãþi supravieþuirea pacienþilor. Punfrecvent probleme de diagnostic diferenþial, atâtclinic, cât ºi dermatoscopic ºi histopatologic,implicând numeroase entitãþi benigne ºi maligne.Prezenþa metastazelor poate fi uneori debilitantã,cu leziuni ulcerative, sângerânde, care producimpotenþã funcþionalã ºi afecteazã calitatea vieþiipacienþilor. Existã numeroase opþiuni pentrumanagementul acestor leziuni disponibile lamomentul actual, cu rate satisfãcãtoare derãspuns terapeutic, care însã totdeauna trebuie sãia în considerare extensia bolii, caracteristicilepacientului ºi comorbiditãþile acestuia.

was used in liver function studies. It is a 10%injectable solution used for melanoma skinmetastases that aims to obtain a systemicantitumoral response, currently in phase III trials.Phases I and II noticed a long term tumoralregression, with minimal systemic toxicity [47, 57].

Systemic therapies can be used in patientsthat were unresponsive or not eligible for localtherapies (with extensive cutaneous lesions).Available therapies include target therapies oMAP Kinases in melanoma with BRAF mutations(Vemurafenib, Dabrafenib, Trametinib) [69, 70]and immunotherapy for immune system check-point molecules like CTL4 (Ipilimumab) [71],PD1 and PD1-L (Nivolumab, Pembrolizumab)[72, 73]. They can be used according to patientcharacteristics, for patients with extensivemetastatic disease, unresponsive to other loco-regional therapies or as first-line therapies inpatients with concomitant visceral metastases[57].

Conclusions

Melanoma skin metastases are a frequentevent in the disease’s natural history, with abetter prognosis than visceral metastases. Earlydiagnosis can improve patient survival. Theyfrequently raise differential diagnosis issues,dermatoscopical as well as histopathological,involving both benign and malignant entities.Metastases may sometimes be a debilitatingdisease, with bleeding, ulcerated lesions that leadto functional impairment and that affect patientquality of life. There are numerous therapeuticoptions available for the management of theselesions, with satisfactory response rates, but thatmust always take into account the diseaseextension, patient characteristics and comor-bidities must always be taken into account.

106

DermatoVenerol. (Buc.), 60: 87-108

Bibliografie/Bibliography

1. Leiter U, E.T., Garbe C., Epidemiology of skin cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol., 2014. 810: p. 120-40.2. Kurtis B. Reed, R.H.C.-N., and Jerry D. Brewer, The cutaneous manifestations of metastatic malignant melanoma.

International Journal of Dermatology, 2012. 51: p. 243–249.3. Lookingbill DP, S.N., Helm KF, Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020

patients. J Am Acad Dermatol, 1993. 29: p. 228–236.4. Charles M. Balch, J.E.G., Seng-jaw Soong, Final Version of 2009 AJCC Melanoma Staging and Classification. J Clin

Oncol, 2009 27(36): p. 6199–6206.5. Bedrosian I, F.M., Guerry Dt, Elenitsas R, Schuchter L, Mick R et al. , Incidence of sentinel node metastasis in patients

with thin primary melanoma (≤ 1 mm) with vertical growth phase. Ann Surg Oncol 2000. 7: p. 262–267.6. WE Damsky, N.T.a.M.B., Melanoma metastasis: new concepts and evolving paradigms. Oncogene 2014. 33: p.

2413–2422.7. Bautista NC, C.S., Anders KH, Benign melanocytic nevus cells in axillary lymph nodes. A prospective incidence and

immunohistochemical study with literature review Am J Clin Pathol, 1994. 102: p. 102–108.8. Kienast Y, v.B.L., Fuhrmann M, Klinkert WE, Goldbrunner R, Herms J et al, Real-time imaging reveals the single steps

of brain metastasis formation. Nat Med, 2010. 16: p. 116–122.9. Ian C. MacDonald, A.C.G.a.A.F.C., Cancer spread and micrometastasis development: Quantitative approaches for in vivo

models. BioEssays, 2002. 24(10): p. 885–893.10. JD Shields, M.B., H Rigby, SJ Harper, PS Mortimer, JR Levick, A Orlando and DO Bates, Lymphatic density and

metastatic spread in human malignant melanoma. British Journal of Cancer, 2004. 90: p. 693 – 700.11. Luzzi KJ, M.I., Schmidt EE, Kerkvliet N, Morris VL, Chambers AF et al., Multistep nature of metastatic inefficiency:

dormancy of solitary cells after successful extravasation and limited survival of early micrometastases. Am J Pathol, 1998.153: p. 865–873.

12. IJ, F., Metastasis: guantitative analysis of distribution and fate of tumor embolilabeled with 125 I-5-iodo-20-deoxyuridine. JNatl Cancer Inst, 1970. 45: p. 773–782.

13. Patel JK, D.M., Pickren JW, Moore RH, Metastatic pattern of malignant melanoma. A study of 216 autopsy cases. Am JSurg 1978. 135: p. 807–810.

14. Schon CA, G.C., Ramaswamy A, Barth PJ, Splenic metastases in a large unselected autopsy series. Pathol Res Pract,2006. 202: p. 351–356.

15. Ossowski L, A.-G.J., Dormancy of metastatic melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res, 2010. 23: p. 41–56.16. J, F., Role of angiogenesis in tumor growth and metastasis. Semin Oncol 2002. 29(6 Suppl 16): p. 15–18.17. Eyles J, P.A., Wang X, Toh B, Prakash C, Hong M et al, Tumor cells disseminate early, but immunosurveillance limits

metastatic outgrowth, in a mouse model of melanoma. J Clin Invest, 2010. 120: p. 2030–2039.18. Balch CM, H.A., Sober AJ, Soong SJ., Cutaneous Melanoma, 4th edn. 2003, Quality Medical Publishing, St Louis,

MO, USA.19. Klein, C.A., Parallel progression of primary tumours and metastases. Nature Reviews, Cancer, 2009. 9.20. Klein, N.H.S.a.C.A., Genetic disparity between primary tumours, disseminated tumour cells, and manifest metastasis.

International Journal of Cancer, 2010. 126(3): p. 589–598.21. Haass, N.K., Smalley, K.S., Li, L., and Herlyn, M., Adhesion, migration and communication in melanocytes and

melanoma. Pigment Cell Res., 2005. 18: p. 150–159.22. Russell R. Braeuer, I.R.W., Chang-Jiun Wu, Aaron K. Moble1, Takafumi Kamiya, and E.S.a.M. Bar-Eli, Why is

melanoma so metastatic? Pigment Cell Melanoma Res., 2013. 27: p. 19–36.23. Bar-Eli, M., Role of interleukin-8 in tumor growth and metastasis of human melanoma. Pathobiology, 1999. 67: p. 12–18.24. Varney, M.L., Johansson, S.L., and Singh, R.K., Distinct expression of CXCL8 and its receptors CXCR1 and CXCR2 and

their association with vessel density and aggressiveness in malignant melanoma. Am. J. Clin. Pathol, 2006. 125: p.209–216.

25. Mu, H., Calderone, T.L., Davies, M.A., Prieto, V.G., Wang, H., Mills, G.B., Bar-Eli, M., and Gershenwald, J.E.,Lysophosphatidic acid induces lymphangiogenesis and IL-8 production in vitro in human lymphatic endothelial cells. Am.J. Pathol, 2012. 180: p. 2170–2181.

26. Bar-Eli, V.O.M.a.M., Inflammation and melanoma metastasis. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res, 2009. 22: p. 257–267.27. Hood, J.L., San, R.S., and Wickline, S.A, Exosomes released by melanoma cells prepare sentinel lymph nodes for tumor

metastasis. Cancer Res, 2011. 71: p. 3792–3801.28. Joyce, J.A., and Pollard, J.W., Microenvironmental regulation of metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer, 2009. 9: p. 239–252.29. Wei, X., Walia, V., Lin, J.C. et al., Exome sequencing identifies GRIN2A as frequently mutated in melanoma. Nat. Genet,

2011. 43: p. 442–446.

107

DermatoVenerol. (Buc.), 60: 87-108

30. Stark, M.S., Woods, S.L., Gartside, M.G. et al., Frequent somatic mutations in MAP3K5 and MAP3K9 in metastaticmelanoma identified by exome sequencing. Nat. Genet, 2012. 44: p. 165–169.

31. Berger, M.F., Hodis, E., Heffernan, T.P. et al., Melanoma genome sequencing reveals frequent PREX2 mutations. Nature,2012. 485: p. 502–506.

32. Karjalainen, J.M., Kellokoski, J.K., Eskelinen, M.J., Alhava, E.M., and Kosma, V.M., Downregulation of transcriptionfactor AP-2 predicts poor survival in stage I cutaneous malignant melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol, 1998. 16: p. 3584–3591.

33. Dobroff, A.S., Wang, H., Melnikova, V.O., Villares, G.J., Zigler, M., Huang, L., and Bar-Eli, M., Silencing cAMP-response element-binding protein (CREB) identifies CYR61 as a tumor suppressor gene in melanoma. J. Biol. Chem., 2009.284: p. 26194–26206.

34. Bhoumik, A., Ivanov, V., and Ronai, Z., Activating transcription factor 2-derived peptides alter resistance of human tumorcell lines to ultraviolet irradiation and chemical treatment. Clin. Cancer Res., 2001. 7: p. 331–342.