cattel

Transcript of cattel

IPOLOGIA FACTORIALISTA R B CATTELL

TIPOLOGIA FACTORIALISTA R. B. CATTELL

Raymond Bernard Cattell (N. 1905) a fost unul din psihologii moderni, de inalta contributie, la dezvoltarea psihologiei contemporane. A studiat, intai, fizica si chimia, care I-au creat o optica deosebit de implicata, in exactitati si sistematizari, ca si in preocupari pentru extinderea conceptuala si metodologica a psihologiei, fata de care, I-a acaparat un interes deosebit, pentru care, a inceput sa se pregateasca in psihologie. A fost influentat de Ch. E. Spearman (1863-1945), cel ce a implicat in psihologia moderna, optica factorialista. Cattell a fost interesat, mai ales, de problemele inteligentei, ale temperamentului, si apoi, ale personalitatii, cea mai mare parte a activitatii sale stiintifice, pana in zilele noastre. A fost implicat, in activitati, la Clark University (USA), apoi la Harvard, si in continuare, la Universitatea din Illinois, unde a fost succesorul lui Charmicael. In 1949, s-a creat Institutul de Testare a Personalitatii si Abilitatilor, la care a lucrat, si pe care, le-a dezvoltat foarte mult. L-a preocupat mult, dezvoltarea psihologiei, constituirea de coerente, in corpul acestei stiinte, si implicarea in uzanta, a unei tehnologii complexe adecvate, si pentru implicarea psihologiei, in stiintele de suport ale vremii. Cattell a fost influentat, si de Allport, mai ales de teoria personalitatii, dezvoltata de acesta.

Testul de personalitate construit de R. B. Cattell este cunoscut sub denumirea P.F.16 (testul de personalitate factorial de 16 factori).

Cattell a diferentiat din multitudinea potentiala de factori, ce se afla in compozitia personalitatii, 16 ca fiind mai importanti. El a notat factorii implicati, cu litere, pentru a evita definitii controversate, si pentru a conversa, forme de relationare factoriale. Fara indoiala, acea conotatie, este datorata, in parte, spiritului sau, format sub incidentele chimiei. De altfel, o astfel de notatie permite o mai facila operare si relationare factoriala. Cattell a considerat ca, exista doua categorii mari de factori. Unii ce se manifesta (constienti) si altii ce se manifesta voalati (fiind inconstienti). Acestia din urma au fost 4 in P.F.16. Factorii pusi in evidenta de Cattell, prin testul sau de personalitate, sunt bivalenti, cu conotatii de “+” si “-” (plus si minus). Prezentarea acestor factori permite, din capul locului, o impartire tipologica, in 16 grupe mari, legate de dominatia unui anumit factor, din cei 16, si o tipologie de 32 de tipuri, in conditiile implicatiei, valorilor plus si minus, la fiecare factor implicat in test. Ca atare, tipologia implicata in testul lui R.B.Cattell, este una dintre cele mai ample, si se afla in corcondanta cu cel putin doua deziderate, ce se constituie in psihoogia diferentiala moderna. Unul dintre deziderate se refera la cresterea relativa de cuprindere a diferentierii in tipologii, iar a doua priveste implicarea unui model cu dominante si submisii de caracteristici psihice, in modelul oferit. 11326iox52hqm1h

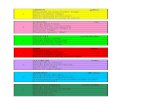

Dam mai jos factorii implicati in tipologia lui Cattell.

A. Factor de schizotimie (-), si Afectotimie (+) oq326i1152hqqm

In ipostaza (-) e vorba de o personalitate rece, rezervata, detasata, in genere, fata de situatii, putin sociabila si introvertita.

In varianta (+) se pune in evidenta o personalitate deschisa, cooperanta, calda, sociabila si introvertita.

B. Factorul ce se refera la Inteligenta

In caz de (-) este vorba de o personalitate slab inteligenta, cu dominatie de gandire concreta, adaptativa, cu spirit analitic, uneori excesiv, incapabil de generalizari coerente si de abstractizari.

In caz de (+) se exprima inteligenta abstracta, inalta, spirit viu si activ, cu posibilitati achizitive foarte mobile.

C. Factorul de manifestare a Eului (in analiza acestuia se tine seama si de factorul E.)

Cand C este corelat (-) cu E (-) se pune in evidenta o persoana instabila, nerealista, sugestionabila, imitativa, cu o natura emotionala excesiva si sensibila.

Cand se coreleaza C (+) cu E(+) se exprima o personalitate cu maturitate si stabilitate emotionala, calma, neinfluentabila si realista.

D. Si factorul D este corelat cu factorul E si cu factorul B si are conotatie privind dominatia si submisia.

In caz de (-) submisie e vorba de o persoana modesta, docila si conventionala.

In caz de (+) dominatie, personalitatea in cauza este sigura de sine, autoritara si neconventionala. La acestea se adauga independenta evidenta in comportamente.

E. Factor de expansivitate si nonexpansivitate.

In caz de (-) persoana in cauza este prudenta, dispune de o comunicativitate slaba, un introspectionism cu tendinte pesimiste.

In caz de (+) e vorba de persoane expansive cu structuri relativ superficiale, logoreice impulsive, dar si entuziaste.

F. Factor de forta al Eului, exprimat prin dependenta-independenta.

In caz de (-) persoana este dependenta, pe de o parte in principii, iar pe de alta parte este conventionala.

In caz de (+) se evidentiaza un Eu, dar, mai ales, un Supraeu corectiv si cenzurat puternic, fapt ce, creeaza personalitatii in cauza, un caracter ferm, simtul datoriei, perseverenta, afirmativ cu onestitate.

G. Factor de anxietate

In varianta (-) e vorba de persoane neincrezatoare, timide, inchise in sine si timorate.

In varianta (+) persoana in cauza este sociabila, indrazneata, intreprinzatoare, disponibila la inovatii, spontana si indrazneata.

H. Factor de afectivitate

In caz de (-) este vorba de o persoana dura, insensibila, satisfacuta de sine.

In caz de (+) se exprima o persoana sensibila, tandra, dependenta.

L. Factor de paroxism- paranoism

In caz de (-) este vorba de o persoana dificila, egocentrica, mereu geloasa, suspicioasa.

In caz de (+) persoana in cauza, este acomodabila, increzatoare, dar necompetitiva, in general.

M. Factor de conventionalism

In caz de (-) se exprima persoane conventionale, dar practice, lipsite de imaginatie, dar rationale.

In caz de (+) e vorba de persoane neconventionale, boeme, originale, imaginative.

N. Factor de variabilitate

In caz de (-) se manifesta personalitati simple, naturale, directe, relativ sentimentale, cu clarviziune, cinice si de rafinament.

In caz de (+) e vorba de persoane increzatoare, calme, fara nelinisti, angoase si temeri.

Q. Factorul incredere- neincredere

In caz de (-) e vorba de persoane nelinistite, depresive, adesea neincrezatoare.

In caz de (+) e vorba de personalitati calme, increzatoare in sine si in altii, faara angoase si temeri.

Q1. Factor de conservatorism, radicalism

Prima varianta se exprima prin persoane traditionaliste, ce accepta confruntari, fara comentarii. Acestor persoane le place, sa conserve tot felul de lucruri. Sunt conservatoare si la propriu si la figurat.

Varianta a doua, se refera la persoane radicaliste, critice, dure si inovatoare, cu o curiozitate dezvoltata.

Q2. Factor de dependenta- independenta

Prima varianta este a persoanelor dependente, si cu atasament excesiv, fata de grupul de apartenenta, fara opinii personale.

A doua varianta are, in vedere, persoane cu opinii si decizii proprii, originale, inclusiv in actiuni, detasate, discrete, fata de grupul de aparteneta.

Q3. Factor de integrare slaba sau buna.

Prima varianta se refera la personalitati neimpacate cu sine, supuse permanent impulsurilor.

A doua varianta se refera la personalitati, ce se controleaza permanent, sunt integre, dar si, formaliste si vanitoase.

Q4. Factor de destindere, tensiune

Prima varianta are in atentie personalitati calme, nepasatoare, satisfacute, nefrustrate si nefrustrante.

A doua varianta se refera la personalitati mereu tensionate de ceva, incordate, mereu surmenate, surescitate si frustrate.

Dupa cum, se poate lesne vedea, 6 factori sunt legati de afectivitate (anxietate).

Se reproseaza factorialistilor, implicatia analizei cantitative matematice implicate in corelatiile, dintre ei, pentru a se calcula corelatia si saturatia diferentiala factoriala. In genere, se poate spune, ca ar exista atatia factori, cate forme de expresie se manifesta. Analiza factoriala ramane un instrumentar, o constructie matematica, ce pune in evidenta aspecte cantitative. Fara indoiala, acestea au rostul sa stabileasca finetea caracteristicilor, ceea ce, constituie un suport, pentru evidentierea calitativa specifica.

Contributions and Limitations of Cattell's Sixteen Personality Factor Model

Heather M. FehriingerRochester Institute of Technology

Personality traits and scales used to measure traits are numerous and commonality amongst the traits and scales is often difficult to obtain. To curb the confusion, many personality psychologists have attempted to develop a common taxonomy. A notable attempt at developing a common taxonomy is Cattell's Sixteen Personality Factor Model based upon personality adjectives taken form the natural language. Although Cattell contributed much to the use of factor analysis in his pursuit of a common trait language his theory has not been successfully replicated.

Science has always strived to develop a methodology through which questions are answered using a common set of principles; psychology is no different. In an effort to understand differing personalities in humans, Raymond Bernard Cattell maintained the belief that a common taxonomy could be developed to explain such differences.

Cattell's scholarly training began at an early age when he was awarded admission to King's College at Cambridge University where he graduated with a Bachelor of Science in Chemistry in 1926 (Lamb, 1997). According to personal accounts, Cattell's socialist attitudes, paired with interests developed after attending a Cyril Burt lecture in the same year, turned his attention to the study of psychology, still regarded as a philosophy (Horn, 2001). Following the completion of his doctorate studies of psychology in 1929 Cattell lectured at the University at Exeter where, in 1930, he made his first contribution to the science of psychology with the Cattell Intelligence Tests (scales 1,2, and 3). During fellowship studies in 1932, he turned his attention to the measurement of personality focusing of the understanding of economic, social and moral problems and how objective psychological research on moral decision could aid such problems (Lamb, 1997). Cattell's most renowned contribution to the science of psychology also pertains to the study of personality. Cattell's 16 Personality Factor Model aims to construct a common taxonomy of traits using a lexical approach to narrow natural language to standard applicable personality adjectives. Though his theory has never been replicated, his contributions to factor analysis have been exceedingly valuable to the study of psychology.

Origins of the 16 Personality Factor ModelIn developing a common taxonomy of traits for the 16 Personality Factor model, Cattell relied heavily on the previous work of scientists in the field. Previous development of a list of personality descriptors by Allport and Odbert in 1936, and Baumgarten's similar work in German in 1933, focused on a lexical approach to the dimensions of personality. Since psychology, like most other sciences, requires a descriptive model to be effective, the construction of a common taxonomy is necessary to successful in explaining personality simplistically (John, 1990). Already focused on the understanding of personality as it pertains to psychology, Cattell set out to narrow the work already

completed by his predecessors. The goal of the research is to achieve integration as it relates to language and personality, that is, to identify the personality relevant adjectives in the language relating to specific traits.

The lexical approach to language is creates the foundation of a shared taxonomy of natural language of personality description (John, 1990). Historically, psychologists relied on such natural language to aid in the identification of personality attributes for such taxonomy. The first step in such a process was to narrow all adjectives within a language to those relating to personality descriptions, as it provided the researchers with a base guiding such a lexical approach. When working with a limited set of variables or adjectives within a language progressed from spoken word as it evolved throughout its progression. Since there are finite sets of adjectives in a language, the narrowing of the variables into base personality categories becomes necessary as multiple adjectives can express similar meanings within the language (John, 1999).

In the process of developing a taxonomy, a process that had taken predecessors sixty years up to this point, Allport and Odbert systematized thousands of personality attributes in 1936. They recognized four categories of adjectives in developing the taxonomy including personality traits, temporary states highly evaluative judgments of personally conduct and reputation, and physical characteristics. Personality traits are defined as "generalized and personalized determining tendencies--consistent and stable modes of an individuals adjustment to their environment" (John, 1999) as stated by Allport and Odbert in their research. Each adjective relative to personality falls within one of the previous categories to aid in the identification of major personality categories and creates a primitive taxonomy, which many psychologists and researchers would elaborate and build upon later. Norman (1967) divided the same limited set of adjectives into seven categories, which, like Allport and Odbert's categories, where all mutually exclusive (John, 1999). Despite this, work from both parties have been classified as containing ambiguous category boundaries, resulting in the general conviction that such boundaries should be abolished and the work has less significance than the earlier judgment.

Factor AnalysisIntroduced and established by Pearson in 1901 and Spearman three years thereafter, factor analysis is a process by which large clusters and grouping of data are replaced and represented by factors in the equation. As variables are reduced to factors, relationships between the factors begin to define the relationships in the variables they represent (Goldberg & Digman, 1994). In the early stages of the process' development, there was little widespread use due largely in part to the immense amount of hand calculations required to determine accurate results, often spanning periods of several months. Later on a mathematical foundation would be developed aiding in the process and contributing to the later popularity of the methodology. In present day, the power of super computers makes the use of factor analysis a simplistic process compared to the 1900's when only the devoted researchers could use it to accurately attain results (Goldberg & Digman, 1994).

In performing a factor analysis, the single most import factor to consider is the selection of variables as considerations such as domain, where a single domain results in the highest accuracy, and other representative variables related to a single domain would provide a more accurate outcome (Goldberg & Digman, 1994). Exploratory factor analysis governs a single domain while confirmatory factor analysis, often less accurate and more difficult to calculate, governs several domains. In terms of variables, it is unlikely to see a factor analysis with fewer than 50 variables. In those situations, another statistical equation may be a better, easier consideration to process the information. A standard sample size for such a function would range between 500 to 1,000 participants (Goldberg & Digman, 1994).

Cattell, another champion of the factor analysis methodology, believed that there are three major sources of data when it comes to research concerning personality traits (Hall & Lindzey, 1978). L-Data, also referred to as the life record, could include actual records of a person's behavior in society such as court records. Cattell, however, gathered the majority of L-Data from ratings given by peers. Self -rating questionnaires, also known as Q-Data, gathered data by allowing participants to assess their own behaviors .The third source of Cattell's data the objective test, also known as T-Data, created a unique situation in which the subject is unaware of the personality trait being measured (Pervin & John, 2001).

With the intent of generality, Cattell's sample population was representative of several age groups including adolescents, adults and children as well as representing several countries including the U.S., Britain, Australia, New Zealand, France, Italy, Germany, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, India, and Japan (Hall & Lindzey, 1978).

Through factor analysis, Cattell identified what he referred to as surface and source traits. Surface traits represent clusters of correlated variables and source traits represent the underlying structure of the personality. Cattell considered source traits much more important in understanding personality than surface traits (Hall& Lindzey, 1978). The identified source traits became the primary basis for the 16 PF Model.

The 16 Personality Factor Model aims to measure personality based upon sixteen source traits. Table 1 summarizes the surface traits as descriptors in relation to source traits within a high and low range.

Critical ReviewAlthough Cattell contributed much to personality research through the use of factor analysis his theory is greatly criticized. The most apparent criticism of Cattell's 16 Personality Factor Model is the fact that despite many attempts his theory has never been entirely replicated. In 1971, Howarth and Brown's factor analysis of the 16 Personality Factor Model found 10 factors that failed to relate to items present in the model. Howarth and Brown concluded, “that the 16 PF does not measure the factors which it purports to measure at a primary level (Eysenck & Eysenck, 1987) Studies conducted by Sell et al. (1970) and by Eysenck and Eysenck (1969) also failed to verify the 16 Personality Factor

Model's primary level (Noller, Law, Comrey, 1987). Also, the reliability of Cattell's self-report data has also been questioned by researchers (Schuerger, Zarrella, & Hotz, 1989).

Cattell and colleagues responded to the critics by maintaining the stance that the reason the studies were not successful at replicating the primary structure of the 16 Personality Factor model was because the studies were not conducted according to Cattell's methodology. However, using Cattell's exact methodology, Kline and Barrett (1983), only were able to verify four of sixteen primary factors (Noller, Law & Comrey, 1987).

In response to Eysenck's criticism, Cattell, himself, published the results of his own factor analysis of the 16 Personality Factor Model, which also failed to verify the hypothesized primary factors (Eysenck, 1987).

Despite all the criticism of Cattell's hypothesis, his empirical findings lead the way for investigation and later discovery of the 'Big Five' dimensions of personality. Fiske (1949) and Tupes and Christal (1961) simplified Cattell's variables to five recurrent factors known as extraversion or surgency, agreeableness, consciousness, emotional stability and intellect or openness (Pervin & John, 1999).

Cattell's Sixteen Personality Factor Model has been greatly criticized by many researchers, mainly because of the inability of replication. More than likely, during Cattell's factor analysis errors in computation occurred resulting in skewed data, thus the inability to replicate. Since, computer programs for factor analysis did not exist during Cattell's time and calculations were done by hand it is not surprising that some errors occurred. However, through investigation into to the validity of Cattell's model researchers did discover the Big Five Factors, which have been monumental in understanding personality, as we know it today.

Table 1. Primary Factors and Descriptors in Cattell's 16 Personality Factor Model (Adapted From Conn & Rieke, 1994).

Descriptors of Low RangePrimary Factor

Descriptors of High Range

Reserve, impersonal, distant, cool, reserved, impersonal, detached, formal, aloof (Sizothymia)

Warmth Warm, outgoing, attentive to others, kindly, easy going, participating, likes people (Affectothymia)

Concrete thinking, lower general mental capacity, less intelligent, unable to handle abstract problems (Lower Scholastic Mental Capacity)

Reasoning

Abstract-thinking, more intelligent, bright, higher general mental capacity, fast learner (Higher Scholastic Mental Capacity)

Reactive emotionally, changeable, affected by feelings, emotionally less stable, easily upset (Lower Ego Strength)

Emotional Stability

Emotionally stable, adaptive, mature, faces reality calm (Higher Ego Strength)

Deferential, cooperative, avoids conflict, submissive, humble, obedient, easily led, docile, accommodating (Submissiveness)

Dominance Dominant, forceful, assertive, aggressive, competitive, stubborn, bossy (Dominance)

Serious, restrained, prudent, taciturn, introspective, silent (Desurgency)

Liveliness

Lively, animated, spontaneous, enthusiastic, happy go lucky, cheerful, expressive, impulsive (Surgency)

Expedient, nonconforming, disregards rules, self indulgent (Low Super Ego Strength)

Rule-Consciousness

Rule-conscious, dutiful, conscientious, conforming, moralistic, staid, rule bound (High Super Ego Strength)

Shy, threat-sensitive, timid, hesitant, intimidated (Threctia)

Social Boldness Socially bold, venturesome, thick skinned, uninhibited (Parmia)

Utilitarian, objective, unsentimental, tough minded, self-reliant, no-nonsense, rough (Harria)

Sensitivity Sensitive, aesthetic, sentimental, tender minded, intuitive, refined (Premsia)

Trusting, unsuspecting, accepting, unconditional, easy (Alaxia)

Vigilance Vigilant, suspicious, skeptical, distrustful, oppositional (Protension)

Grounded, practical, prosaic, solution orientated, steady, conventional (Praxernia)

Abstractedness Abstract, imaginative, absent minded, impractical, absorbed in ideas (Autia)

Forthright, genuine, artless, open, guileless, naive, unpretentious, involved (Artlessness)

Privateness Private, discreet, nondisclosing, shrewd, polished, worldly, astute, diplomatic (Shrewdness)

Self-Assured, unworried, complacent, secure, free of guilt, confident, self satisfied (Untroubled)

Apprehension

Apprehensive, self doubting, worried, guilt prone, insecure, worrying, self blaming (Guilt Proneness)

Traditional, attached to familiar, conservative, respecting traditional ideas (Conservatism)

Openness to Change

Open to change, experimental, liberal, analytical, critical, free thinking, flexibility (Radicalism)

Group-oriented, affiliative, a joiner and follower dependent (Group Adherence)

Self-Reliance Self-reliant, solitary, resourceful, individualistic, self sufficient (Self-Sufficiency)

Tolerated disorder, unexacting, flexible, undisciplined, lax, self-conflict, impulsive, careless of social rues, uncontrolled (Low Integration)

Perfectionism

Perfectionistic, organized, compulsive, self-disciplined, socially precise, exacting will power, control, self –sentimental (High Self-Concept Control)

Relaxed, placid, tranquil, torpid, patient, composed low drive (Low Ergic Tension)

Tension Tense, high energy, impatient, driven, frustrated, over wrought, time driven. (High Ergic Tension)

Peer Commentary

Maybe We're Asking the Wrong QuestionJennifer A. Dructor

Rochester Institute of Technology

There is no doubt in my mind that Raymond Bernard Cattell was an intelligent man. Beginning his college days at age 16 in the field of chemistry and attaining a doctorate degree in psychology immediately thereafter along is an impressive accomplishment. Working with renowned psychologists like Charles Spearman, one of the originators of factor analysis, only adds to this credibility. Nevertheless, I have to question the methodology that contributed to the Sixteen Factor Model of Personality Cattell created.

It is no secret that despite multiple attempts to demonstrate the validity of the model, it has never actually been replicated. Even Cattell himself was not able to duplicate his findings, which in my opinion speaks volumes. He did not have the advanced technology to work with like computer software that virtually eliminates human error, which begs the question "How do we know if any of the conclusions were reasonable or valid at all?" Although a useful model known as the "Big Five factors" was developed through investigations into Cattell's theory, I do not feel satisfied with any of the conclusions drawn as to why this model is not conclusive.

People often forget that before becoming what we consider a science all fields of study came from philosophy. Is it even possible to come up with an accurate taxonomy of universally common traits? Are the methods of factor analysis and the lexical approach to this question even valid themselves? I think we often get ourselves into trouble when we try to draw conclusions about people using mathematical equations and scientific methods. Yes, it has been widely found that factor analysis has been able to find correlations between various items within psychology; but, I ask, in what situations does one analyze a person's behavior or personality by pulling out that calculator, pencil and paper? The connation I get whenever I read about someone trying to explain people using math is, "How does this make sense?" I think to have a truly deep understanding of a person's traits we must first turn to philosophy and answer the question, "Are there any

universal traits, and what reasonable explanations can be provided to support the answer?"

Cognitive relativism states that there are no universal truths about the world and that there are no intrinsic characteristics, but only different ways of interpretation (Sterba, 2000). Every culture has its own views of the world, what is right and wrong, and how people should live their lives. Every culture has its own interpretation and holds different meanings for various things; so, how can anything be universally true? As Americans, being citizens of one of the most powerful nations of the world, we often feel that our beliefs and opinions hold true over most nations; but who is to say that our conclusions extend to any nation outside of our culture? To even come close, I think a team of individuals from every nation would have to analyze their own culture and put their findings together. Only then, I believe could these methods be relied on to draw accurate conclusions.

If one day we are able to decisively answer the previously mentioned questions, I think the lexical approach could be a useful tool. It is logical to think that the more words in existence to describe one meaning symbolizes how important it is to society. Yet this method does not include all parts of speech and cannot really accommodate traits that are ambiguous to most people. The lexical approach has been used to find popular meanings, and factor analysis has been used to determine traits that are correlated, but how does this determine the existence of the traits? The communication process human beings went to from primitive days until now was long and complicated. People might not have always been able to communicate all of their thoughts, feelings, or emotions clearly, and we cannot exactly go back in time to find the answers.

Although I understand the burning desire to classify traits in order to better understand people, I am not sure that questions about human nature can ever actually be explained. Although our hearts are in the right place, often I feel that our need to figure people out clouds our judgment. I too find myself yearning to better understand others and myself; but I am not yet convinced that any of our methods are valid in doing so. We need philosophy because of our natural tendency not to critically examine our beliefs and to accept accounts of the world given to us because some intelligent person like a psychologist says so or even because a book on the topic tells us so. How well did psychologist Raymond Cattell question his predecessors?

Peer Commentary

Is the Development of a Hierarchy of Personality From a Flawed Base Trustworthy?

Mallory R. HarveyRochester Institute of Technology

The five-factor model of personality is based on the fundamental principles and goals of Cattell's 16 Personality Factor Model. Cattell's approach to understanding the factors of

personality was lexical. He acquired previous compilations of the most common adjectives describing personality and subdivided and excluded terms, ending up with 35 clusters of descriptors. A factor analysis of the 35 clusters resulted in the formation of a hierarchy, which consisted of 16 personality traits. Cattell's results were never duplicated, and his method of organization was discarded. Although his method of analysis was discorroborated, the currently popular five-factor model of personality was developed from Cattell's clusters of personality descriptions. Basing a method of analysis off of a flawed method without questioning the original breakdown of the lexical arrangement leaves doubts as to the comprehensiveness of the five-factor model.

Cattell's 35 clusters of personality traits were further limited by Fiske, who used a subset of only 22 clusters and ran a factor analysis. The results of Fiske's analysis provided a five-factor solution. Tupes and Christal completed further analysis, using larger samples. Their results also corroborated a five-factor hierarchal model of personality (Larsen & Buss, 2002). The most recent form of Cattell's 16 Personality Factor approach declares that the 16 personality traits are results of five major personality factors. This is quite similar to the five-factor approach in that the global properties of personality are restricted to five characteristics. Recent studies have shown both methods of analysis measure comparable personality factors quite reliably (Rossier, de Stadelhofen, & Berthound, 2004).

Recent criticisms of the five-factor model have looked at the possible exclusion of other universal personality factors. Evidence for a sixth factor is strong, and there is some evidence for a seven-factor model. A cross-cultural study completed by Aston et al. (2004) suggests that a factor containing the aspects of Honesty or Humility should be added to the current five-factor model to make it more comprehensive. Further evidence has suggested that a global property of personal attractiveness may be a feasible addition to the current model (Larsen & Buss, 2002). The numerous exclusions marked by recent research suggest that the foundations of the five-factor model should be reevaluated.

The five-factor model has also been criticized for being unable to concretely label the fifth factor. There has been much debate as to the validity of either Intelligence or Imitation as the fifth factor. Comparing different cultures has caused much of the dispute over the labeling of the fifth factor. Different cultures value different personality characteristics, and this contributes to the problem of defining the fifth factor (Larsen & Buss, 2002). The difference in values leads to the conclusion that, globally, there cannot be a consensus on a fifth trait and calls into question the possibility of a globally reliable hierarchy of personality.

Cattell paved the way for the development of the five-factor model of personality, but the process developed has not been entirely substantiated. Many aspects of personality appear to have been overlooked in the process of clumping together and discarding adjectives in the original lexical breakdown performed by Cattell. There has been a great influx of support for the addition of a sixth factor of personality. Much thought should be given to how statistical processes are performed and what in reality is being measured.

Author Response

Factor Analysis QuestionedHeather M. Fehringer

Rochester Institute of Technology

A question has been posed about the efficacy of using factor analysis as an approach to identifying individual traits. Trait theorists employ three main approaches in their research, the lexical approach, the statistical approach, and the theoretical approach. Most trait psychologists have employed one or more of the three main approaches. Cattell based his work on previous information gathered through the lexical approach of Allport and Odbert and the statistical approach, factor analysis. Simply put, factor analysis is a process by which large clusters and grouping of data are replaced and represented by factors. As variables are reduced to factors, relations between the factors begin to define the relations in the variables they represent (Goldberg & Digman, 1994).

I for one am not a mathematician and will not attempt to explain the methodology any further. I would refer anyone looking for a further in-depth explanation of the methodology of factor analysis to the chapter, "Revealing Structure in the Data: Principles of Exploratory Factor Analysis," by Goldberg and Digman (1994).

ReferencesAston, M. C., Lee, K., Perugini, M., Szarota, P., de Vries, R. E., Di Blas, L., Boies, K., & De Raad, B. (2004). A six-factor structure of personality-descriptive adjectives: Solutions from psycholexical studies in seven languages. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 356-366.

Cattell, R. B. (1990). Advances in Cattellian personality theory. In L. A. Pervin (Ed.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 101-110). New York: Guildford.

Conn, S. R., & Rieke, M. L. (1994). The 16PF Fifth Edition Technical Manual. Champagne, IL: Institute for Personality and Ability Testing, Inc.

Eysenck, H. J., & Eysenck, M. W. (1985). Personality and individual differences: A natural science approach. New York: Plenum.

Goldberg, L. R., & Digman, J. M. (1994). Revealing structure in the data: Principles of exploratory factor analysis. In S. Strack & M. Lorr (Eds.), Differentiating normal and abnormal personality (pp. 216-242). New York: Springer.

Lamb, K. (1997). Raymond Bernard Cattell: A lifetime of achievement. Mankind Quarterly, 38, 127.

Hall, C. S., & Lindzey, G. (1978). Theories of personality (3rd ed.). New York: Wiley.

Hall, C. S., Lindzey, G., & Campbell, J. B. (1998). Theories of personality (4th ed.). New York: Wiley.

Horn, J. (2001). Raymond Bernard Cattell (1905-1998). American Psychologist, 56, 71-72.

John, O. P. (1990) The Big Five factor taxonomy: Dimensions of personality in the natural language and in questionnaires. In L. A. Pervin (Ed.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 66-100). New York: Guildford.

John, O. P. (1999). The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (2nd ed., pp. 102-138). New York: Guildford.

Larsen, R. J., & Buss, D. M. (2002). Personality psychology: Domains of knowledge about human nature. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Noller, P., & Law, H., & Comrey, A. L. (1987). The Cattell, Comrey, and Eysenck personality factors compared: More evidence for five robust factors? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 775-782.

Pervin, L. A., & John. O. P. (2001). Personality theory and research (8th ed.). New York: Wiley.

Rossier, J., de Stadelhofen, F. M., & Berthound, S. (2004). The hierarchical structures of the NEO-PI-R and the 16 PF 5. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 20, 27-38.

Schuerger, J. M., Zarella, K. L., & Hotz, A. S. (1989). Factors that influence the temporal stability of personality by questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 777-783.

Sterba, J. (2000). Ethics: Classical Western texts in feminist and multicultural perspectives. New York: Oxford University Press.

Last modified May 2004Visited times since May 2004Comments?

Home to Personality Papers

Home to Great Ideas in Personality

TEST DE PERSONALITATE - R.B. CATTELL

(manual de utilizare)

CUPRINS: R.B.Cattell şi testul său de personalitate (în loc de introducere)

1.Chestionarul

2.Descrierea factorilor de personalitate şi semnificaţia valorilor acestora

3.Aspecte metrologice ale testului

4.Cheia testului

5.Etalonul

6.Utilizarea testului

R.B.CATTELL ŞI TESTUL SĂU DE PERSONALITATE: 16PF

(În loc de introducere)

Unul dintre marii specialişti care s-au preocupat de problematica personalităţii umane a fost şi psihologul american R.B.CATTELL. Acesta s-a născut în Anglia, în anul 1905, trăgându-se dintr-o familie de ingineri cu origini mai vechi în Scoţia şi cu o linie de rudenie îndepărtată cu Mc Ken Cattell, unul dintre părinţii psihologiei americane din secolul trecut, care, între altele, a folosit pentru prima dată termenul de test mental. La 19 ani R.B. Cattell a obţinut la Universitatea din Londra diploma în fizică şi chimie. Sperman şi Bot i-au deschis gustul pentru psihologie, în special pentru măsurarea capacităţilor umane. În 1937 se stabileşte în SUA ca cercetător în subordinea lui Thorndike la Teachers College (Columbia University). În 1945 funcţionează ca profesor la Universitatea Illinois unde s-a preocupat în special de măsurarea trăsăturilor de personalitate.

Printre instrumentele elaborate se numără şi testul (chestionarul) 16PF.

Testul la care ne referim, elaborat pe baza unor cercetări ample şi ca un instrument matematic-statistic elevat şi rafinat, –analiză multifactorială– s-a dovedit a fi un instrument valid pentru cunoaşterea oamenilor, fapt pentru care a fost preluat de către foarte mulţi psihologi pentru a-l utiliza în psihodiagnosticarea personalităţii.

A fost preluat şi de către specialiştii din Franţa, unde psihologia cunoaşte o dezvoltare considerabilă. Specialiştii francezi au adoptat testul lui Cattell, l-au tipărit şi apoi l-au pus în circulaţie în Europa, iar în anul 1971, am intrat şi noi în posesia acestuia. Iniţial testul a fost tradus şi aplicat unui număr restrâns de subiecţi cunoscuţi, ocazie cu care s-a constatat că instrumentul la care ne referim ar putea să fie deosebit de util pentru populaţia românrească cu condiţia ca el să fie adaptat la realitatea socială de la noi. În această ordine de idei, Centrul de organizare şi cibernetică în construcţii s-a dovedit un loc prielnic pentru experimentarea lui de către Cornel Cotor, Aurel Jula şi Constantin Zahirnic.

Acţiunea de adaptare a testului a început cu renunţarea la forma B a acestuia (din considerente de economisire a timpului) şi adptarea formei A de aşa manieră încât aceasta să ne satisfacă exigenţele. În acest context, forma A a fost aplicată la peste 1000 de subiecţi –cadre de conducere şi specialişti de categorii şi vârste diferite din construcţii– participanţi la programele de specializare organizate de COCC. Din cei peste 1000 de subiecţi testaţi au fost separate la întâmplare 300 de profile pe baza cărora s-a elaborat un nou etalon.

Dat fiind numărul mare de subiecţi care necesita a fi examinaţi cu acest instrument, am fost obligaţi să procedăm la informatizarea lui (transpunerea lui pe calculator, pentru a fi prelucrat şi interpretat). Aşa a luat naştere, în anul 1972, la COCC, varianta 1 232x234c 6PF cu prelucrare şi interpretare automată a datelor, realizată de specialiştii mai sus citaţi.

Acest instrument dovedindu-se a fi valid şi operant, permiţând testarea, prelucarea şi interpretarea rezultatelor câtorva sute de subiecţi, în cursul unei singure zile, cu eforturi şi cheltuieli relativ mici, a fost preluat de un număr mare de specialişti din ţară pentru a fi utilizat.

Testul CATTELL 16PF dispune de următoarele componente:

1. CHESTIONARUL propriu-zis cu instrucţiuni de aplicare atât pentru corecţie şi interpretare tradiţională.

2. FILE DE RĂSPUNS: pentru prelucrarea tradiţională.

3. GRILĂ PENTRU CORECŢIE.

4.FOAIA DE PROFIL.

5.ETALONUL pentru prelucrarea tradiţională.

6.CHEIA testului sau modul de cotare al itemilor.

1. CHESTIONARUL propriu-zis este conceput în ideea de a furniza informaţii esenţiale referitoare la structura personalităţii subiecţilor investigaţi.

Este alcătuit din 187 itemi (întrebări) care urmăresc evidenţierea a 16 trăsături de personalitate (factori de personalitate de prim ordin) plus 4 factori de personalitate de ordinul doi[1].

Întrebările sunt formulate astfel încât să permită trei variante de răspuns (afirmativ, negativ şi nedecis) excepţie făcând factorul B care solicită un singur răspuns, cel corect.

Cei 16 factori de personalitate vizaţi, dispun de un număr inegal de itemi (13-26) în funcţie de complexitatea şi dificultatea de a putea fi surprinşi prin modul de formulare al acestora. Altfel spus, anumite trăsături de personalitate, mai complexe şi mai dificil de surprins şi evidenţiat, necesită un număr mai mare de întrebări, adresate din perspective diferite.

Fiecare item al chestionarului cotează pentru un singur factor de personalitate. Toţi itemii dispun ce aceeaşi pondere, aspect rezultat din analiza factorială efectuată de autor. În funcţie de maniera în care sunt formulate întrebările, de sensul polarizării acestora, cotarea se face în felul următor:

– când polarizarea este pozitivă, prima variantă de răspuns este cotată cu două puncte, a doua variantă cu un punct şi a treia variantă cu zero puncte;

– când polarizarea este negativă, varianta a treia este cotată cu două puncte, varianta a doua cu un punct, iar prima variantă cu zero puncte. Fac excepţie de la această regulă itemii de la factorul B (inteligenţă) care sunt cotaţi cu un punct pentru rezolvarea corectă şi cu zero puncte pentru rezolvarea incorectă.

Subiecţilor cărora li se aplică acest chestionar, în funcţie de variantele de răspuns pe care le aleg pot obţine între zero şi maximum de puncte pentru fiecare factor de personalitate. Itemii sub forma întrebărilor formulate au fost repartizaţi astfel încât să prezinte o variaţie pentru subiecţi. Chestionarul a fost astfel întocmit încât să reducă pe cât posibil riscul simulării deliberate, majoritatea întrebărilor fiind indirecte, legate de aspecte cărora subiectul nu le sesizează relaţia cu însuşirea de personalitate vizată, dar despre care se ştie, prin studiul corelaţiilor că o testează.

APLICAREA chestionarului 16PF se poate face individual sau colectiv, potrivit instrucţiunilor cuprinse în primele două pagini ale acestuia. Timpul de aplicare este variabil, în funcţie de subiecţii examinaţi. Persoanelor care citesc mai repede le sunt suficiente 60 minute pentru parcurgere şi completare; celor cu posibilităţi mai reduse le sunt necesare 120 minute. La COCC, aplicării acestui test i s-a alocat 120 minute, inclusiv instruirea în vederea aplicării.

2.DESCRIEREA FACTORILOR DE PERSONALITAE INVESTIGAŢI ŞI SEMNIFICAŢIA VALORILOR ACESTORA

Interpretarea factorilor de prim ordin (PRIMARI)

Factorul A exprimă schizotimia-ciclotimia

Schizotimia caracterizează un tip de caracter normal, închis în sine, hipersensibil, deşi în aparenţă rece, tinzând spre inhibiţie. Ciclotimia exprimă o dispoziţie spre o evoluţie tonico-afectivă ciclică cu alternanţe între stări active, euforice şi depresive, atonie. Iată însuşirile bipolare evidenţiate: distanţă–apropiere; “răceală” – “căldură”; rigiditate–adptabilitate; bănuială–încredere; duritate–maleabilitate; indiferenţă–interes faţă de alţii; opozanţă(critic)–conlucrabilitate(serviabilitate); “depărtare”–“apropiere”; dispreţuire–preţuire.

–A Notele mici obţinute la factorul A exprimă: rezervă, detaşare, tendinţă de critică, distanţare, scepticism, rigiditate, dispreţ. Persoanele care obţin note mici preferă lucrurile în locul oamenilor, le place să lucreze singuri, evitând confruntările, sunt exigenţi şi rigizi în normele personale; sunt critici, opozanţi şi duri.

+A Notele mari obţinute la factorul A exprimă: “deschidere”, “căldură”, afectuozitate, un caracter plăcut, agreat. Persoanele din această categorie sunt apropiate, primitoare, tandre, amabile, capabile să-şi exprime emoţiile, dispun de capacitate de adaptare, sunt sensibile şi se interesează de alţii. Au preferinţă pentru profesiunile cu posibilităţi de contacte personale, organizând cu plăcere activităţi colective şi participă la ele, sunt generoşi în relaţiile personale şi nu le este frică de critică.

FACTORUL B vizează nivelul intelectual: “cultivat”–“necultivat”, perseverenţa–delăsarea sau lipsa acesteia, conştiinţa valorii şi conştiinciozitatea şi opusul acestora (ignoranţa şi lipsa de scrupule).

–B Notele mici exprimă o inteligenţă “discretă”, o gândire concretă, lentoarea “spiritului” (“cade greu fisa”), atunci când este vorba de înţelegere şi învăţare, este “greoi” şi înclinat spre o interpretare concretă şi literală a fenomenelor. Această situaţie poate să fie reflexul unei instruiri şi educaţii neadecvate, fie efectul unei sărăcii intelectuale de ordin psihopatologic.

+B Notele ridicate reflectă un nivel intelectual ridicat exprimat de o gândire abstractă dezvoltată (capacitatea de a opera cu noţiuni din ce în ce mai abstracte, de a opera cu simboluri, de a sesiza rapid aspectele esenţiale dintre lucruri şi fenomene, de a găsi soluţii, etc.).

FACTORUL C exprimă forţa Eului în termeni psihoanalitici, vizând următoarele aspecte bipolare: intoleranţă la frustare–maturitate emoţională, stabilitatea–instabilitatea emoţională, nervozitatea–calmul, astenia–tonicitatea psihică, liniştea–agitaţia.

–C Nota scăzută arată un caracter emotiv, nestatornic, agitat, influenţabil, impresionabil, iritabil, nesatisfăcut.

+C Nota ridicată arată un caracter stabil emoţional, maturitate, calm, realism şi capacitate de a susţine moralul altora.

FACTORUL E se referă la subordonare–dominare, influenţă, esxprimând supunere–dominare, siguranţă de sine–nesiguranţă, independenţă–dependenţă de opinii, amabilitate–severitate, naturaleţe în comportare–seriozitate afectată (nenaturală), conformism–noncorformism, siguranţă(neşovăire)–nesiguranţă(uşor încurcat, tulburat), capacitate de a capta atenţia–incapabil de această acţiune.

–E Nota scăzută evidenţiază: modestie, supunere, conformism, linişte, acomodare. Cu alte cuvinte, tendinţa de a ceda uşor altora, de a fi docil, simţ dezvoltat al culpabilităţii şi obsesie faţă de convenienţe.

+E Nota ridicată pune în evidenţă siguranţa de sine, caracterul independent–dominant, încăpăţânarea şi tendinţa spre agresivitate, independenţa în opinii şi tendinţa de a face ceea ce doreşte, oponenţă şi autoritarism.

FACTORUL F vizează expansivitatea exprimată de comunicativitate–taciturnie, însufleţire–lipsa de însufleţire (deprimare), vioiciune–lentoare.

–F Nota mică pune în evidenţă prudenţa, gravitatea, seriozitatea, rezerva, introspecţia. Oamenii din acestă categorie au tendinţă spre îndărătnicie, pesimism, spre o prudenţă excesivă şi aroganţă.

+F Nota ridicată arată indiferenţă, nepăsare, entuziasm, impulsivitate. Persoanele din această categorie sunt vesele şi voioase, vorbăreţe, deschise şi sincere. Atrag privirile altora pentru a fi alese lideri.

FACTORUL G se referă la forţa Supra-Eului, la regulile de convieţuire socială, punând în evidenţă respectul–eludarea regulilor, hotărârea–nehotărârea, responsabilitatea–fuga de răspundere, maturitatea emoţională–nerăbadarea(pretenţiozitatea), stabilitate în conduită(activ, harnic)–instabil(delăsător, leneş), prevenitor cu alţii–neprevenitor, etc.

–G Nota mică arată oportunism, ocolirea regulilor şi legilor şi lipsa simţului datoriei sau tendinţă de delăsare şi neglijenţă. Oamenii din această categorie nu fac eforturi pentru a participa la acţiunile colective, manifestând independenţă de orice influenţă a grupului. Sunt toleranţi la tensiuni psihice.

+G Notele ridicate arată onestitate, integritate morală, perseverenţă, seriozitate şi atenţie la regulile de convieţuire. Cei ce fac parte din această categorie sunt exigenţi, cu un simţ al datoriei şi responsabilităţii ridicat, sunt prevăzători, conştiincioşi, moralizatori, preferând tovărăşia oamenilor serioşi şi harnici decât a celor amuzanţi.

FACTORUL H vizează timiditatea–îndrăzneala, cu cortegiile care le însoţesc, după cum urmează: tendinţa de întoarcere spre sine(interiorizare)–sociabilitate, prudenţă–îndrăzneală, interes viu pentru sexul opus–lipsă de interes pentru această realitate, conţtiinciozitate–superficialitate, sentimente şi interese artistice–lipsa acestor sentimente şi interese, rezonanţă afectivă–“răceală” sau lipsă de rezonanţă afectivă.

–H Nota scăzută exprimă timiditate, atitudine timorată, neîncredere în forţele proprii, prudenţa execesivă. Asemenea oameni încercă să treacă neobservaţi, au un sentiment de inferioritate, exprimându-se nesigur şi cu reţinere, exteriorizându-se greu, nu agrează profesiile care presupun contacte personale, iar în relaţiile cu semenii lor preferă cercuri restrânse de prieteni. Tendinţă de dezinteres pentru persoanele de sex opus.

+H Nota ridicată exprimă îndrăzneală, destindere, spontaneitate. Persoanele din această categorie dispun de o puternică rezonanţă afectivă, acceptând cu uşurinţă refuzurile nedelicate ale altora sau situaţii conflictuale dificile, greu de suportat. Sunt întreprinzătoare, acordă un interes viu persoanelor de sex opus, petrrecându-şi mult timp vorbind.

FACTORUL I (raţionalitate–afecţiune), evidenţiază următoarele aspecte bipolare: maturitate emoţională–imaturitate, independenţă–dependenţă în gândire, satisfacţie de sine–insatisfacţie, aspru(uneori critic)–amabil(apropiat), simţul artistic–lipsa simţului artistic.

–I Nota scăzută exprimă: realism şi uneori duritate, satisfacţie referitoare la propria persoană, raţionalitate. Persoanele cu notă ridicată se caracterizează prin spirit practic, independenţă şi sunt capabile să-şi asume responsabilităţi. Sunt sceptice, au tendinţe spre insensibilitate, duritate, cinism şi dispreţuire. Le plac activităţile cu caracter practic.

+I Nota ridicată arată: tandreţe şi dependenţă afectivă, sensibilitate exagerată şi imaturitate afectivă. Persoanele cu note ridicate sunt visătoare, depinzând afectiv de alţii şi solicită atenţie din partea altora, nedispunând de simţul practic. Au aversiune pentru persoanele mai puţin rafinate sau pentru aspectele triviale. Sunt predispuse să coboare moralul unui grup printr-o atitudine infantilă negativă.

FACTORUL L (atitudine încrezătoare–suspiciune), exprimă următoarele caracteristici contrare: tendinţa spre invidie–lipsa de invidie, timiditatea şi ruşinea–îndrăzneala şi chiar neruşinarea, vioiciunea–morocănozitatea(ursuzitatea), adaptabilitatea–rigiditatea, interesul faţă de alţii–indiferenţa faţă de alţii.

–L Nota scăzută arată o atitudine încrezătoare, acomodanţă, capacitate de contacte personale, lipsa invidiei, preocupare de soarta altora, capacitatea de a lucra în echipă.

+L Nota ridicată arată suspiciune (bănuială), rigiditate, interesul faţă de problemele personale (egoism, egocentrism), dezinteres faţă de alţii, neputinţa de a lucra în echipă (nu este suportat de către coechipieri datorită atitudinilor acestuia).

FACTORUL M (preocupare faţă de aspecte practice–ignoranţă faţă de aspecte practice), vizează următoarele aspecte contrare: convenţionalismul–neconvenţionalismul, logicul–imaginativul, însuşirea de a exprima încredere–lipsa acesteia, elecvenţa–inelocvenţa, “sângele rece”–emotivitatea exagerată.

–M Nota scăzută evidenţiază spiritul practic, scrupulozitatea, convenţionalismul, corectitudinea. Persoanele din această categorie sunt grijulii în a face “ceea ce se cuvine”, acordând o atenţie deosebită problemelor practice, neacţionând la întâmplare, interesându-se de detalii, autocontrolându-se exagerat, dând dovadă de “sânge rece” în caz de pericol, uneori le lipseşte imaginaţia.

+M Nota ridicată arată puţină preocupare de convenienţe, originalitate şi ignoranţă faţă de realităţile cotidiene. Persoanele care obţin note ridicate sunt preocupate de idei măreţe, neglijând oamenii şi realităţile materiale. Uneori sunt: extravagante dispunând de reacţii emoţionale violente. Pot să împiedice acţiuni colective în virtutea calităţilor lor.

FACTORUL N se referă la clarviziune–naivitate după cum urmează: cutezanţă (viclenie)–neîndemânare în această privinţă, interes faţă de alţii–dezinteres faţă de alţii şi interes faţă de sine, satisfacţie–insatisfacţie, comportare naturală şi tendinţă spre corectitudine–abilitate, subtilitate, viclenie.

–N Nota scăzută exprimă un caracter drept, natural, sentimental, naiv. Persoanele din această categorie sunt spontane, uneori repezite şi stângace în “a face curte” şi a se face plăcute.

+N Nota ridicată arată abilitate, subtilitate, perspicacitate, cutezanţă, interes, viclenie. Asemenea persoane dispun de capacitatea de analiză şi sinteză ridicate, fiindu-le străin sentimentalismul. Adoptă în activitatea lor şi în relaţiile cu alţii maniere intelectualiste, încercând să epateze, pentru atingerea scopului.

FACTORUL Q oferă informaţii asupra calmului şi neliniştii.

–Q Nota scăzută exprimă calm (armonie, linişte) şi încredere. Asemenea persoane manifestă o atitudine generală de indiferenţă, încredere puternică în forţele proprii, siguranţă în posiblitatea lor de a-şi rezolva problemele.

+Q Nota ridicată arată nelinişte, agitaţie, deprimare şi tendinţă de culpabilitate. Asemenea persoane dispun de presentimente şi “gânduri negre”. În situaţii dificile prezintă nelinişte infantilă; se simt persecutate şi eliminate din grup şi incapabile să se integreze.

FACTORUL Q1 pune în evidenţă radicalismul–conservatorismul.

–Q1 Nota scăzută exprimă conservatorismul, care se defineşte prin următoarele caracteristici: conformism şi toleranţă la deficienţele şi dificultăţile tradiţiei, încredere în ceea ce a apucat să creadă, accepţiune faţă de toate “adevărurile primare” în ciuda contradicţiilor, chiar când posibilitatea de îmbunătăţire este evidenţiată; prudenţă şi suspiciune faţă de orice idee nouă, ceea ce determină întârzierea sau opoziţia faţă de orice schimbare.

+Q1 Nota ridicată exprimă radicalismul care se caracterizează prin: spirit novator, sesizarea şi critica a tot ceea ce este vechi şi perimat, libertatea în gândire şi acţiune scepticism şi curiozitate faţă de ideile vechi, capacitate de a suporta bine inconvenienţele şi schimbarea, interes pentru probleme intelectuale şi îndoială faţă de aşa-zisele adevăruri esenţiale.

FACTORUL Q2 oferă informaţii despre atitudinea de dependenţă–independenţă faţă de grup.

–Q2 Nota scăzută arată dependenţă socială şi ataşament faţă de grup, preferinţa pentru muncă şi deciziile în colectiv. Persoanelor cu note scăzute la acest factor le place ca societatea (grupul) să-i aprobe şi să-i admire, au tendinţa de a urma calea majorităţii întrucât le lipsesc soluţiile personale.

+Q2 Nota ridicată indică hotărâre şi independenţă socială. Asemenea persoane fac opinie separată, fără a arăta dominanţă faţă de alţii, nu pentru că nu i-ar simpatiza ci pentru că nu au nevoie de susţinerea lor.

FACTORUL Q3 se referă la integrare.

–Q3 Nota scăzută exprimă lipsa de autocontrol, conflictul cu sinele, neglijenţa convenienţelor şi supunerea faţă de impulsuri, neglijenţa faţă de cerinţele vieţii sociale. Asemenea persoane nu sunt prea prevenitoare, nici scrupuloase sau cugetate, uneori se simt neadaptate.

+Q3 Nota ridicată exprimă un autocontrol ridicat, formalism şi conformism faţă de anumite idei personale, tendinţă spre circumspecţie. Persoanele cu note ridicate dispun de “amor propriu”, sunt vanitoase şi ţin la reputaţia lor, uneori sunt îndărătnice.

FACTORUL Q4 pune în evidenţă tensiunea energetică.

–Q4 Nota scăzută evidenţiază destinderea, liniştea, apatia, mulţumirea şi nepăsarea; lispa sentimentului de frustraţie. Persoanele din această categorie pot ajunge leneşe, neeficiente în măsura în care le lipseşte ambiţia; denotă experienţă modestă.

+Q4 Nota ridicată evidenţiază încordare, frustrare, iritare, surmenaj. Evidenţiază persoane surescitabile, agitate, neliniştite, irascibile. Asemenea persoane, deşi sunt surmenate, nu pot rămâne inactive; în grup nu contribuie decât foarte puţin la coeziunea acestuia, la disciplină sau la conducere. Insatisfacţia acestor persoane reflectă un exces de energie stimulată dar nedescărcată, neinvestită.

FACTORII DE ORDINUL DOI:

1. ADAPTABILITATEA –ANXIETATEA

2. INTROVERSIA –EXTROVERSIA

3. DINAMISMUL –INHIBIŢIA

4. INDEPENDENŢA –SUPUNEREA

Calculul notelor standard la factorii de ordinul doi se face după cum urmează:

1.ADAPTABILITATEA–ANXIETATEA 2.DINAMISMUL–INHIBIŢIA

2x Nota L 2x Nota C

+3x Nota O +2x Nota E

+4x Nota Q4 +2x Nota F

–2x Nota C +2x Nota N

–2x Nota H –4x Nota A

–2x NotaQ3 –6x Nota I

–2x Nota M

+ constanta 34 + constanta 69

Suma rezultată se împarte la 10 Suma rezultată se împarte la 10

3.INTROVERSIA–EXTROVERSIA 4.INDEPENDENŢA–SUPUNEREA

2x Nota A 4x Nota E

+3x Nota E +3x Nota M

+4x Nota F +4x Nota Q1

+5x Nota H +4x Nota Q2

–2x Nota Q2 –3x Nota A

–2x Nota G

– constanta 11 – constanta 4

Suma rezultată se împarte la 10 Suma rezultată se împarte la 10

3.ASPECTE METROLOGICE ALE TESTULUI

a.FIDELITATEA chestionarului a fost verificată prin retestarea a 152 de subiecţi testaţi, după o perioadă de 6 luni, cu ocazia participării acestora la ciclul doi al programului de perfecţionare la COCC. Cu acest prilej se costată la toţi subiecţii examinaţi că se menţin aceleaşi tendinţe ale valorilor însuşirilor la ambele testări deşi la nici un subiect nu s-au obţinut tablouri identice în ceea ce priveşte notele brute.

b.VALIDITATEA chestionarului rezultă din coeficientul mare de coincidenţă între valorile obţinute prin testarea subiecţilor şi imaginea furnizată de persoane care cunoşteau subiecţii examinaţi. În acest sens am consultat 86 de persoane cărora le-am cerut să indice în note de la 1 la 10 nivelul celor 16 factori de personalitate, în funcţie de modul în care i-au perceput. Transformând aceste note în calificative s-a obţinut o coincidenţă de 71% cu nivelurile rezultate prin testare; 22% din informaţii au indicat niveluri din trepte proxime (superioare sau inferioare) ale profilului rezultat prin testare.

Cât priveşte validitatea celor patru indicatori sintetici, s-a solicitat opinia a 82 de subiecţi testaţi pentru a confirma sau infirma nivelul acestora. Peste 93% din acei subiecţi s-au recunoscut, confirmând valabilitatea testului; aproape 7% au afirmat că cifrele nu reflectă o situaţie strictă.

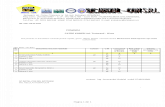

SENSIBILITATEA pusă în evidenţă de repartiţia rezultatelor este exprimată de valorile cuprinse în tabelul de mai următor:

Factorii de personalitate Distribuţia subiecţilor pe factori de nivel

FS S M R FR

A 15 28 72 25 12

B 9 23 76 29 15

C 11 27 74 30 10

E 14 25 73 29 11

F 10 23 79 27 13

G 11 30 69 28 14

H 9 26 81 24 12

I 10 29 79 24 10

L 14 30 70 27 11

M 15 24 70 30 13

N 12 30 75 25 10

Q 11 27 77 23 14

Q1 13 24 79 21 15

Q2 11 22 73 25 11

Q3 9 29 79 23 12

Q4 10 25 79 24 14

După câte se poate observa, rezultatele obţinute se repartizează astfel încât respectă regula normalităţii şi exigenţele atât din punct de vedere al numărului de subiecţi cât şi al diferenţei mici dintre subiecţii testaţi.

*repartiţia rezulatelor pe 5 niveluri au fost denumite: FS-foarte scăzut, S-scăzut, M-mediu, R-ridicat, FR-foarte ridicat

4.CHEIA TESTULUI (a=2 pct., b=1 pct., c=0 pct.)

FactorNotă brută

(puncte)Poziţia răspunsului cotat cu două puncte

a b c

A 20 3, 52, 101, 126, 176 26, 27, 51, 76, 151

B 13 152, 177, 178 28, 53, 54, 78,103,128

77,102,127,153

C 26 4, 30, 55, 104, 105, 130, 179 5, 29, 79, 80, 129, 154

E 26 7, 56, 131, 155, 156, 180, 181 6, 31, 32, 57,81,106

F 26 33, 58, 83, 132, 133, 182, 183 8, 82, 107, 108, 157, 158

G 20 109, 134, 160, 184, 185 9, 34, 59, 84, 159

H 26 10, 36, 110, 111, 135, 136, 186 35, 60, 61, 85, 86, 161

I 20 12, 37, 112, 138, 163 11, 62, 87, 137, 162

L 20 38, 88, 113, 114, 164 13, 63, 64, 89, 139

M 26 39, 40, 65, 91, 115, 116, 140 14, 15, 90, 141, 165, 166

N 20 17, 42, 117, 142, 167 16, 41, 66, 67, 92

O 26 18, 43, 69, 94, 118, 119, 143 19, 44, 68, 93, 144, 168

Q1 20 20, 46, 70, 145, 169 21, 45, 95, 120, 170

Q2 20 47, 71, 72, 146, 171 22, 96, 97, 121, 122

Q3 20 48, 73, 98, 148, 173 23, 24, 123, 147, 172

Q4 26 49, 50, 74, 99, 124, 149, 174 25, 75, 100, 125, 150, 175

Notă: Răspunsurile cu varianta a 2-a de la toţi factorii, cu excepţia factorului B, vor fi cotate cu 4 puncte. La factorul B, răspunsul corect va fi cotat cu un punct.

ETALONUL TESTULUI pentru cei 16 factori de personalitate

FactorFoarte scăzut

(FS)

Scăzut

(S)

Mijlociu

(M)

Ridicat

(R)

Foarte ridicat

(R)

A 0-1 2-4 5-6 7 8-9 10 11 - 12 13-14

15-20

B 0-3 4-5 6 7 8 9 - 10 11 12 13

C 0-5 6-7 8-9 10-11 12-13 14-15 16-17

18 19 20-21

22-26

E 0-3 4-5 6 7-9 10 11 12 13-14

15-16 17-19

20-26

F 0-2 3-4 5 6 7-8 9-11 12 13 14-17 18 19-26

G 0-6 7-9 10-11 12 13-14 15 16 17 18 - 19-20

H 0-4 5-6 7-8 9-10 11 12-13 14-15

16-17

18-21 22-24

25-26

I 0-2 3-4 5 6-8 9 10 11-12

13 14 15-17

18-20

L 0-2 3-4 5 6 7 8 9 10-11

12 13-14

15-20

M 0-3 4-5 6-7 8 9-10 11 12 13 14 15-16

17-26

N 0-5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14-16

17-20

Q 0-2 3-4 6 7 8-9 10-11 12 13-14

15 16-21

22-26

Q1 0-2 3-4 5 6 7-8 9 10 11 12 13-14

15-20

Q2 0-2 3-4 5 6 7-8 9 10-11

12 13-14 15 16-20

Q3 0-4 5-6 7-9 10 11 12-13 14 15 16 17 18-20

Q4 0-3 4-5 6-7 8 9-10 11-12 13-14

15-16

17 18-21

22-26

ETALONUL PENTRU FACTORII DE ORDINUL DOI

NIVELUL

FS S M R FR

ADAPTABILITATEA –ANXIETATEA –20–(–1,7)

–1,6–(+2,4)

2,5–6,7

6,8–10,4

peste 10,4

INTROVERSIA –EXTROVERSIA

–5,1–(0,7)

–0,6–(2,3)

2,4–5,8

5,9–8,3

peste 8,3

DINAMISMUL –INHIBIŢIA –3,1–(+7,8)

7,9–13,00

13,1–16,3

16,4–19,9

peste 19,9

INDEPENDENŢA –SUPUNEREA –5–(+5,5)

5,6–8 8,1–10

10,1–13,5

peste 13,5

*Valorile cuprinse între 13–16 la introversie–extroversie exprimă ambivertismul.

Valorile sub 13 indică introversia, iar cele peste 16 indică extroversia

[1] Factorii de personalitate de ordinul doi sunt obţinuţi din cei 16 factori de personalitate de prim ordin

Classics in the History of PsychologyAn internet resource developed by

Christopher D. GreenYork University, Toronto, Ontario

(Return to Classics index )

V.-MENTAL TESTS AND MEASUREMENTSby Prof. J. McK. Cattell (1890)

First published in Mind, 15, 373-381.

Psychology cannot attain the certainty and exactness of the physical sciences, unless it rests on a foundation of experiment and measurement. A step in this direction could be made by applying a series of mental tests and measurements to a large number of individuals. The results would be of considerable scientific value in discovering the constancy of mental processes, their interdependence, and their variation under different circumstances. Individuals, besides, would find their tests interesting, and, perhaps, useful in regard to training, mode of life or indication of disease. The scientific and practical value of such tests would be much increased should a uniform system be adopted, so that determinations made at different times and places could be compared and combined. With a view to obtaining agreement among those interested, I venture to suggest the following series of tests and measurements, together with methods of making them.[1]

The first series of ten tests is made in the Psychological Laboratory, of the University of Pennsylvania on all who present themselves, and the complete series on students of Experimental Psychology. The results will be published when sufficient data have been collected. Meanwhile, I should be glad to have the tests, and the methods of making them, thoroughly discussed.

The following ten tests are proposed:

I. Dynamometer Pressure. II. Rate of Movement. III. Sensation-areas. IV. Pressure causing Pain. V. Least Noticeable difference in Weight. VI. Reaction-time for Sound. VII. Time for naming Colours. VIII. Bi-section of a 50 cm. Line IX. Judgment of 10 seconds time. X. Number of Letters remembered on once Hearing.

[p.374] It will be noticed that the series begins with determinations rather bodily than mental, and proceeds through psychophysical to more purely mental measurements.[2]

The tests may be readily made on inexperienced persons, the time required for the series being about an hour. The laboratory should be conveniently arranged and quiet, and no spectators should be present while the experiments are being made. The amount of instruction the experimentee should receive, and the number of trials he should be given, are matters which ought to be settled in order to secure uniformity of result. The amount of instruction depends on the experimenter and experimentee, and cannot, unfortunately, be exactly defined. It can only be said that the experimentee must understand clearly what he has to do. A large and uniform number of trials would, of course, be the most satisfactory, the average, average variation, maximum and minimum being recorded. Time is, however, a matter of great importance if many persons are to be tested. The arrangement most economical of time would be to test thoroughly a small number of persons, and a large number in a more rough-and-ready fashion. The number of trials I allow in each test is given below, as also whether I consider the average or 'best' trial the most satisfactory for comparison. Let us now consider the tests in order.

I. Dynamometer Pressure. The greatest possible squeeze of the hand may be thought by many to be a purely physiological quantity. It is, however, impossible to separate bodily from mental energy. The 'sense of effort' and the effects of volition on the body are among the questions most discussed in psychology and even in metaphysics. Interesting experiments may be made on the relation between volitional control or emotional excitement and dynamometer pressure. Other determinations of bodily power could be made (in the second series I have included the 'archer's pull' and pressure of the thumb and fore-finger), but the squeeze of the hand seems the most convenient. It may be readily made, cannot prove injurious, is dependent on mental conditions, and allows

comparison of right-and left-handed power. The experimentee should be shown how to hold the dynamometer in order to obtain the maximum pressure. I allow two trials with each hand (the order being right, left, right, left), and record the maximum pressure of each hand.

II. Rate of Movement. Such a determination seems to be of considerable interest, especially in connexion with the preceding. [p.375] Indeed, its physiological importance is such as to make it surprising that careful measurements have not hitherto been made. The rate of movement has the same psychological bearings as the force of movement. Notice, in addition to the subjects already mentioned, the connexion between force and rate of movement on the one hand and the 'four temperaments' on the other. I am now making experiments to determine the rate of different movements. As a general test, I suggest the quickest possible movement of the right hand and arm from rest through 50 cm. A piece of apparatus for this purpose can be obtained from Clay & Torbensen, Philadelphia. An electric current is closed by the first movement of the hand, and broken when the movement through 50 cm. has been completed. I measure the time the current has been closed with the Hipp chronoscope, but it may be done by any chronographic method. The Hipp chronoscope is to be obtained from Peyer & Favarger, Neuchâtel. It is a very convenient apparatus, but care must be taken in regulating and controlling it (see MIND No. 42).[3]

III. Sensation-areas. The distance on the skin by which two points must be separated in order that they may be felt as two is a constant, interesting both to the physiologist and psychologist. Its variation in different parts of the body (from 1 to 68 mm.) was a most important discovery. What the individual variation may be, and what inferences may be drawn from it, cannot be foreseen; but anything which may throw light on the development of the idea of space deserves careful study. Only one part of the body can be tested in a series such as the present. I suggest the back of the closed right band, between the tendons of the first and second fingers, and in a longitudinal direction. Compasses with rounded wooden or rubber tips should be used, and I suggest that the curvature have a radius of 5mm. This experiment requires some care and skill on the part of the experimenter. The points must be touched simultaneously, and not too hard. The experimentee must turn away his head. In order to obtain exact results, a large number of experiments would be necessary, and all the tact of the experimenter will be required to determine, without undue expenditure of time, the distance at which the touches may just be distinguished.

IV. Pressure causing Pain. This, like the rate of movement, is a determination not hitherto much considered, and if other more important tests can be devised they might be substituted for these. But the point at which pressure causes pain may be an important constant, and in any case it would be valuable in the diagnosis of nervous diseases and in studying abnormal states of consciousness. The determination of any fixed point or quantity in pleasure or pain is a matter of great interest in theoretical and practical ethics, and I should be glad to include. some such test [p.376] the present series. To determine the pressure causing pain, I use an instrument (to be obtained from Clav & Torbensen) which measures the pressure applied by a tip of hard rubber 5 mm. in radius. I am now

determining the pressure causing pain in different parts of the body; for the present series commend the centre of the forehead. The pressure should be gradually increased and the maximum read from the indicator after the experiment is complete. As a rule, the point at which the experimentee says the pressure is painful should be recorded, but in some cases it may be necessary to record the point at which signs of pain are shown. I make two trials, and record both.

V. Least noticeable difference in Weight. The just noticeable sensation and the least noticeable difference in sensation are psychological constants of great interest. Indeed, the measurement of mental intensity is probably the most important question with which experimental psychology has at present to deal. The just noticeable sensation can only be determined with great pains, if at all: the point usually found being in reality the least noticeable difference for faint stimuli. This latter point is itself so difficult to determine that I have postponed it to the second series. The least noticeable difference in sensation for stimuli of a given intensity can be more readily determined, but it requires some time, and consequently not more than one sense and intensity can be tested in a preliminary series. I follow Mr. Galton in selecting 'sense of effort' or weight. I use small wooden boxes, the standard one weighing 100 gms. and the others 101, 102, up to 110 gms. The standard weight and another (beginning with 105 gms.) being given to the experimentee, he is asked which is the heavier. I allow him about 10 secs for decision. I record the point at which he is usually right, being careful to note that he is always right with the next heavier weight.

VI. Reaction-time for Sound. The time elapsing before a stimulus calls forth a movement should certainly be included in a series of psychophysical tests: the question to be decided is what stimulus should be chosen. I prefer sound; on it the reaction-time seems to be the shortest and most regular, and the apparatus is most easily arranged. I measure the time with a Hipp chronoscope, but various chronographic methods have been used. There is need of a simpler, cheaper and more portable apparatus for measuring short times. Mr. Galton uses an ingenious instrument, in which the time is measured by the motion of a falling rod, and electricity is dispensed with, but this method will not measure times longer than about 1/3 sec. In measuring the reaction-time, I suggest that three valid reactions be taken, and the minimum recorded. Later, the average and mean variation may be calculated.[4]

VII. Time for naming Colours. A reaction is essentially reflex, [p.377] and, I think, in addition to it, the time of some process more purely mental should be measured. Several such processes are included in the second series; for the present series I suggest the time needed to see and name a colour. This time may be readily measured for a single colour by means of suitable apparatus (see MIND No. 42), but for general use sufficient accuracy may be attained by allowing the experimentee to name ten colours and taking the average. I paste coloured papers (red, yellow, green and blue) 2 cm. square, 1cm. apart, vertically on a strip of black pasteboard. This I suddenly uncover and start a chronoscope, which I stop when the ten colours have been named. I allow two trials (the order of colours being different in each) and record the average time per colour in the quickest trial.

VIII. Bisection of a 50 cm Line. The accuracy with which space and time are judged may be readily tested, and with interesting results. I follow Mr. Galton in letting the experimentee divide an ebony rule (3 cm. wide) into two equal parts by means of a movable line, but I recommend 50 cm. in place of 1 ft., as with the latter the error is so small that it is difficult to measure, and the metric system seems preferable. The amount of error in mm. (the distance from the true middle) should be recorded, and whether it is to the right or left. One trial would seem to be sufficient.

IX. Judgment of 10 sec. Time. This determination is easily made. I strike on the table with the end of a pencil and again after 10 seconds, and let the experimentee in turn strike when he judges an equal interval to have elapsed. I allow only one trial and record the time, from which the amount and direction of error can be seen.

X. Number of Letters repeated on once Hearing. Memory and attention may be tested by determining how many letters can be repeated on hearing once. I name distinctly and at the rate of two per second six letters, and if the experimentee can repeat these after me I go on to seven, then eight, &c.; if the six are not correctly repeated after three trials (with different letters), I give five, four, &c. The maximum number of letters which can be grasped and remembered is thus determined. Consonants only should be used in order to avoid syllables.

Experimental psychology is likely to take a place in the educational plan of our schools and universities. It teaches accurate observation and correct reasoning in the same way as the other natural sciences, and offers a supply of knowledge interesting and useful to everyone. I am at present preparing a laboratory manual which will include tests of the senses and measurements of mental time, intensity and extensity, but it seems worth while to give here a list of the tests which I look on as the more important in order that attention may be [p.378] drawn to them, and co-operation secured in choosing the best series of tests and the most accurate and convenient methods. In the following series, fifty tests are given, but some of them include more than one determination.

Sight1. Accomodation (short sight, over-sight, and astigmatism). 2. Drawing Purkinje's figures and the blind-spot. 3. Acuteness of colour vision, including lowest red and highest violet visible. 4. Determination of the field of vision for form and colour. 5. Determination of what the experimentee considers a normal red, yellow, green and blue. 6. Least perceptible light, and least amount of colour distinguished from grey. 7. Least noticeable difference in intensity, determined for stimuli of three degrees of brightness. 8. The time a colour must work on the retina in order to produce a sensation, the maximum sensation and a given degree of fatigue. 9. Nature and duration of after-images. 10. Measurement of amount of contrast. 11. Accuracy with which distance can be judged with one and with two eyes.

12. Test with stereoscope and for struggle of the two fields of vision. 13 Errors of perception, including bisection of line, drawing of square, &c. 14. Colour and arrangement of colours preferred. Shape of figure and of rectangle preferred.

Hearing.15. Least perceptible sound and least noticeable difference in intensity for sounds of three degrees of loudness. 16. Lowest and highest lens audible, least perceptible difference in pitch for C, C', C", and point where intervals and chords (in melody and harmony) are just noticed to be out of tune. 17. Judgment of absolute pitch and of the nature of intervals, chords and dischords. 18. Number and nature of the overtones which can be heard with and without resonators. 19. Accuracy with which direction and distance of sounds can be judged. 20. Accuracy with which a rhythm can be followed and complexity of rhythm can be grasped. 21. Point at which loudness and shrillness of sound become painful. Point at which beats are the most disagreeable. 22. Sound of nature most agreeable. Musical tone, chord, instrument and composition preferred.

[p.379] Taste and Smell.23. Least perceptible amount of cane-sugar, quinine, cooking salt and sulphuric acid. and determination of the parts of the mouth with which they are tasted. 24. Least perceptible amount of camphor and bromine. 25. Tastes and smells found to be peculiarly agreeable and disagreeable.