Santana Cetatea Veche Text

-

Upload

micle-dorel -

Category

Documents

-

view

553 -

download

8

Transcript of Santana Cetatea Veche Text

1

Complexul Muzeal Arad

Sântana Cetatea Veche

memoriei arheologilor Mircea Rusu şi Egon Dörner

to the memory of the archaeologists Mircea Rusu and Egon Dörner

o fortificaţie de pământ a epocii bronzului la Mureşul de jos

a Bronze Age earthwork on the lower Mureş

2

3

COMPLEXUL MUZEAL ARAD

SÂNTANA CETATEA VECHE

FLORIN GOGÂLTAN VICTOR SAVA

ARAD 2010

A BRONZE AGE EARTHWORK ON THE LOWER MUREŞ

O FORTIFICAŢIE DE PĂMÂNT A EPOCII BRONZULUI LA MUREŞUL DE JOS

4

Text: Florin Gogâltan, Victor Sava

Fotografii/Photographies: Victor Sava, Florin Mărginean, Zoltán József Botha

Concept & layout: Victor Sava, Roberto Tănăsache

ISBN 978-973-0-09664-4

5

CuprinsContents

Introducere. Introduction / 8

Mureşul de jos. Cadrul fizico-geografic. Lower Mureş. Physical and geographical background / 11

Localizarea fortificaţiei. The location of the earthwork / 13

Istoricul cercetărilor. The state of research / 14

Noile cercetări. The new researches / 25, 27

Descrierea sistemului de fortificare. The description of the earthwork structure / 29

Dimensiunile estimative ale celor trei incinte. The estimate size of the three enclosures / 36

Descoperirile arheologice din jurul fortificaţiei. Archaeological discoveries around the earthwork / 39

Elemente de cronologie relativă şi absolută ale celei de-a treia incinte. Issues on relative and absolute chronology of the

third enclosure / 41

Prieteni sau duşmani. Friends or enemies / 51

Orosháza Nagytatársánc, comitat Békés, Ungaria. Orosháza Nagytatársánc, comitat Békés, Ungaria / 52

Localizarea fortificaţiei. The location of the earthwork / 53

Istoricul cercetărilor. The state of research / 54

6

Munar Wolfsberg - Dealul Lupului, comuna Secusigiu, judeţul Arad, România. Munar Wolfsberg - Dealul Lupului,

Secusigiu commune, Arad County, Romania / 57

Localizarea fortificaţiei. The location of the earthwork / 57

Istoricul cercetărilor. The state of research / 57

Corneşti Iarcuri, comuna Orţişoara, judeţul Timiş, România. Corneşti Iarcuri, comuna Orţişoara, judeţul Timiş,

România / 62

Localizarea fortificaţiei. The location of the earthwork / 62

Istoricul cercetărilor. The state of research / 63, 62

Noile cercetări. The new researches / 67

Topolovăţu Mare Joamba, judeţul Timiş, România. Topolovăţu Mare Joamba, Timiş County, Romania / 69

Localizarea fortificaţiei. The location of the earthwork / 69

Istoricul cercetărilor. The state of research / 70, 69

Noile cercetări. The new researches / 71

Câteva concluzii istorice. Several historic conclusions / 72

Mulţumiri. Acknowledgements / 80

Bibliografie. Bibliography / 83

Fotografii din timpul săpăturii de la Sântana Cetatea Veche campania 2009. Photographies taken during the excavation from

Sântana Cetatea Veche campaign 2009 / 89

7

8

Introducere

Săpăturile arheologice sunt singurele în măsură să ne dezvăluie un trecut despre care nu avem informaţii scrise. Arheologia nu înseamnă căutarea şi descoperirea unor comori şi cu atât mai puţin o viaţă aventuroasă precum cea a personajului de film Indiana Jones. Sperăm că nu-i vom dezamăgi pe cei cărora li se adresează în primul rând această lucrare, pasionaţii de arheologia şi istoria meleagurilor arădene, atenţionându-i că ceea ce urmează este o investigaţie ştiinţifică.

O astfel de cercetare presupune în primul rând o foarte bună cunoaştere a zonei ce urmează a fi studiată. Deplasările pe teren (periegheze), ce necesită aprobări speciale din partea Comisiei Naţionale de Arheologie, se fac în diverse perioade ale anului, pentru alegerea celui mai potrivit loc unde urmează să fie amplasată săpătura arheologică. Dacă această primă etapă nu necesită fonduri deosebite, costurile pentru întocmirea unui plan topografic, fără de care

Introduction

The archaeological excavations represent the only means of unveiling a past time not covered in written documents. Archaeology itself does not signify the search and discovery of treasures, much less the Indiana Jones type of adventurous life. We hope not to disappoint the main target audience of this work, the enthusiasts with a keen interest in the archaeology and history of Arad region, so we would like to forewarn them that this is a scientific undertaking.

Such a research requires in the first place a very solid knowledge of the surveyed area. The archaeological

field surveys, which require special authorizations from the National Archaeological Commission, are performed during different time periods of the year, in order to be able to select the best location for the archaeological site. While this first stage requires relatively little time and expenses, the costs of a topographic plan, of the utmost importance for beginning an archaeological research and later on for

Fig. 1. Harta Bazinului Carpatic cu localizarea fortificaţiei de pământ/Map of the Carpathian Basin with the localisation of the earthwork

9

nu se poate începe o cercetare arheologică şi mai apoi efectuarea unor investigaţii magnetometrice (o tehnică modernă care permite vizualizarea diverselor structuri aflate în sol), aşa cum o cer normele actuale ştiinţifice, depăşeşte deja de cele mai multe ori bugetele instituţiilor de cultură abilitate. Ce este de făcut?

Apelarea la unele fundaţii sau întocmirea unor proiecte de cercetare ce urmează a fi finanţate de către stat ar fi o rezolvare salvatoare. Din nefericire pentru noi arheologii şansele de a obţine bani sunt mici, întotdeauna existând alte domenii prioritare. O altă soluţie ar fi cooptarea unor parteneri străini, dar este posibil ca uneori deciziile să ţină cont doar de interesele celor care asigură finanţarea. Cum s-au făcut totuşi cercetări arheologice la Sântana Cetatea Veche? Aici începe adevărata aventură...

Sântana Cetatea Veche, aşa cum vom vedea, suscită de peste 200 de ani interesul unor specialişti, oameni de cultură sau chiar a unor simpli pasionaţi de vestigiile trecutului.

Mircea Barbu, regretatul arheolog arădean, scria într-un articol din presa anului 1999: această mare fortificaţie de pământ este o enigmă ce cere a fi odată desluşită. Au trecut aproape 50 de ani de când generaţii de arheologi au cunoscut cetatea de la Sântana doar prin trecerile pasagere cu trenul de la Arad la Oradea. Interesul pentru asemenea obiective a renăscut prin dezvoltarea programului Google Earth. Folosirea imaginilor surprinse de sateliţi face posibilă identificarea unor fortificaţii ale căror dimensiuni nu pot fi apreciate de la nivelul

conducting magnetometric investigations (a modern technique which enables the visualization of different structures within the soil), as requested by the applicable scientific guidelines, most of the time exceed the budgets of the appropriate cultural institutions. What can be done?

Appealing to various foundations or preparing research projects, which are to be financed by the state, may be a solution to this problem. Unfortunately, the chances for us, the archaeologists, to obtain funding are very thin, as there are always other priorities. Another solution may be engaging in partnerships with foreign entities, but there is the risk that the personal interests of the people providing the financing would prevail in the decision making process. So, how was it possible to conduct archaeological investigations at Sântana Cetatea Veche? This is where the real adventure begins ...

For more than 200 years, Sântana Cetatea Veche has aroused the interest of specialists, either scholars or simple enthusiasts of past remnants.

The late archaeologist from Arad, Mircea Barbu, wrote in an article published in 1999: this big earth fortification remains a mystery which demands to be unveiled. For almost 50 years generations of archaeologists have been observing the fortress from Sântana cursorily, on occasional train stops on the route from Arad to Oradea. The interest in such archaeological sites has been revived thanks to the development of the Google Earth software. The use of satellite images enables the identification of

10

solului. Impulsionaţi de perspectivele oferite de noile

metode ştiinţifice de investigare, un colectiv de specialişti de la Universitatea de Vest din Timişoara a decis studierea unei alte mari fortificaţii de pământ, cea de la Corneşti Iarcuri, judeţul Timiş. Acest proiect de cercetare s-a dezvoltat cu timpul prin cooptarea altor specialişti din ţară sau străinătate. Au urmat, începând cu toamna anului 2007, sondaje stratigrafice, măsurători magnetometrice şi investigaţii arheologice sistematice. Contextul istoric în care s-a ridicat o fortificaţie de dimensiunile celei de la Corneşti nu putea fi pe deplin înţeles dacă nu se apela la analogiile din epocă. În acest scop cea mai potrivită alegere a fost, bineînţeles, Cetatea Veche de la Sântana.

În paralel cu efectuarea unor cercetări de suprafaţă, apelând la sprijinul generos al colegilor de la Universitatea din Bochum (prof. dr. Tobias Kienlin) şi Universitatea de Vest din Timişoara (lect. dr. Dorel Micle), în primăvara anului 2008 s-au efectuat primele măsurători magnetometrice. Soluţia efectuării unor săpături arheologice s-a concretizat abia în primăvara anului viitor. Amplasarea unei magistrale de gaz ar fi distrus o bună porţiune din fortificaţia de pământ, ceea ce a determinat, conform legislaţiei naţionale şi europene, efectuarea de săpături arheologice preventive. Fondurile primite au asigurat suportul material pentru săpăturile de salvare desfăşurate la Cetatea Veche între 17 septembrie şi 30 noiembrie 2009. Pentru a face cunoscute cercetărilor noastre, am decis publicarea cât mai grabnică

fortifications, whose dimensions cannot be ascertained from ground level.

Encouraged by the perspectives provided by the new scientific research methods, a group of specialists from the West University from Timişoara decided to conduct a research of another great earth fortification, from Corneşti Iarcuri, Timiş County. Over time, that research project expanded due to the recruitment of other specialists from Romania or abroad. Since autumn 2007, stratigraphic samplings, magnetometric scannings and systematic archaeological investigations have been conducted. The historical background leading to the construction of a fortification of such dimensions as the Corneşti fortification, could not have been fully comprehended unless it was compared against a similar construction. Of course, Cetatea Veche, near Sântana was the best choice to this end.

The first magnetometric measurements were performed in spring 2008, concurrently with a surface survey research, thanks to the generous help of the peers from Bochum University (Prof. Dr. Tobias Kienlin) and the West University from Timişoara (Dr. Dorel Micle). The chance to perform archaeological excavations in the area became effective in the spring of the following year. The extension of a main gas pipeline would have destroyed a significant part of the earth fortification, a fact which, according to the national and European legislation, led to the initiation of preventive archaeological excavations. The allocated funds ensured the necessary material

11

a rezultatelor parţiale. Sperăm că atât specialiştii cât şi cei pasionaţi de arheologie vor aprecia efortul nostru, iar viitorul cunoaşterii ştiinţifice a cetăţii de pământ de la Sântana Cetatea Veche se va afla de acum înainte pe un făgaş mai bun.

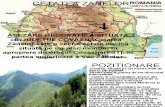

Mureşul de jos. Cadrul fizico-geografic

Câmpia Aradului, cuprinsă între râurile Mureş şi Crişul Alb, reprezintă din punct de vedere genetic o deltă cuaternară a Mureşului, constituită la ieşirea din defileul Şoimoş-Lipova. Partea centrală, în perimetrul marcat de localităţile Socodor, Sântana, Sâmbăteni şi Arad este relativ înaltă şi orizontală, iar spre vest, după o zonă joasă cu tendinţe de înmlăştinire, urmează o porţiune de câmpie înaltă cu caracter tabular (Posea 1997, 375).

În urma numeroaselor cercetări de teren efectuate între 2007 şi 2009, dar şi cu ajutorul fotografiilor aeriene, am putut constata că amplasamentul fortificaţiei a fost ales cu mare grijă. Până la începutul secolului al XIX-lea, când au început marile lucrări de desecare şi îndiguire ale Mureşului, apele râului se revărsau în Câmpia Aradului până la aproximativ 20 km de cursul actual, aproape de sudul oraşului Sântana. Din acest punct de vedere fortificaţia era amplasată ideal, la 1,8 km de cel mai nordic braţ al Mureşului, astfel încât să fie ferită de inundaţii sau înmlăştiniri.

Din cele scrise de Sándor Márki aflăm că până în secolul al XVIII-lea întreaga zonă ar fi fost acoperită

support for the rescue excavations conducted between September 17th and November 30th, 2009. We have decided to publish the partial results as soon as possible, in order to share our research output. We hope that our efforts will be appreciated by scholars as well as archaeology enthusiasts, and that the future scientific research of the earth fortification from Sântana Cetatea Veche shall fall on a better path.

Lower Mureş. Physical and geographical background

From a genetic perspective, the Arad Plain, located between the rivers Mureş and Crişul Alb, is a quaternary delta of the Mureş River, emerged on the exit from Şoimoş-Lipova defile. The central part, limited by the settlements of Socodor, Sântana, Sâmbăteni and Arad, is relatively high and smooth, and towards the Western part, a lower marshy area is followed by a high tabular plain area (Posea 1997, 375).

Following the multiple field researches conducted between 2007 and 2009, as well as the aerial photographs, we determined that the location of the fortification had been chosen very carefully. Until the beginning of the 19th century, when the draining off and embankment of the Mureş River began, the river was flooding into the Arad Plain, on a surface up to almost 20 km far from the present day watercourse, close to the Southern part of Sântana. From this perspective, the fortification was located in the

12

cu păduri de ulm (Ulmus minor), atât de caracteristice zonelor mlăştinoase de câmpie, care au fost ulterior defrişate pentru a face loc agriculturii dar şi distruse de o ciupercă devastatoare (Marki 1882, 119). De altfel şi pe vechiul blazon al comitatului Arad este reprezentat un ulm scos din rădăcini şi susţinut de doi lei. O posibilă reconstituire a mediului ambiant din vechime este oferită de istoricul István Ferenczi: De la actualul oraş Mukacevo (din Ucraina subcarpatică) şi până la actuala capitală a Iugoslaviei timp de luni întregi se întindea o baltă, nu numai în lungul Tisei, ci şi pe cursul inferior al tuturor afluenţilor carpatici. Numai pe la jumătatea verilor uscate, apele intrau în matcă, lăsând în urmă tot anul mlaştini întinse (Ferenczi 1993, 44).

Situată la 15 km vest de Munţii Zărandului, 25 km sud-est de ieşirea Mureşului din zona muntoasă şi 1,8 km de fosta mlaştină, fortificaţia de la Sântana controla defileul Mureşului, dealurile Şiriei şi mai departe zona metaliferă a Munţilor Apuseni. Distanţa relativ mică de la fortificaţie până la ieşirea Mureşului în câmpie se putea parcurge pe jos în aproximativ 5-6 ore, traseul dus-întors putând fi acoperit pe durata unei zile de mers.

ideal place, 1.8 km far from the Northernmost river branch of Mureş, keeping it safe from floods and marshes.

According to the writings of Sándor Márki, until the 18th century the entire area was covered by elm forests

(Ulmus minor), typical of the marshy plains regions, but underwent a process of deforestation later on, to allow the development of agricultural works, and were also destroyed by a devastating fungus (Marki 1882, 119). As a matter of fact, the coat of arms of Arad County includes an uprooted elm tree, supported by two lions. One possible reconstruction of the past environment is supplied by the historian István Ferenczi: All the way from Mukacevo city (from sub-Carpathian Ukraine) to the present day capital of

Yugoslavia, for months in a row a mere was spanning alongside Tisa River and also alongside the inferior river flow of all the Carpathian tributaries. Only during the dry mid-summer time did the waters retreat within the river bed, leaving behind large marshy areas for the rest of the year (Ferenczi 1993, 44).

Located 15 km West of Zărand Mountains, 25 km South-East of the Mureş exit from the mountain region and 1.8 km far from the former marsh, the fortification from Sântana was a strategic control point of the Mureş Defile, Şiria Hills and farther away, of the metalliferous region of the Apuseni Mountains. The relatively short distance between the Mureş exit into the plain and the earthwork could be covered by foot in around 5-6 hours, the round-trip route could be covered in a day’s walk.

Fig. 2. Blazonul vechiului comitat Arad/The coat-of-arms of the old Arad County

13

Localizarea fortificaţiei

Sântana este situată la aproximativ 20 km nord-est de municipiul Arad şi la 5 km est de drumul european Arad-Oradea. Fortificaţia de pământ se găseşte la 5,8 km sud-vest de centrul oraşului Sântana, spre Zimandu Nou, pe partea stângă a şoselei care leagă cele două localităţi.

The location of the earthwork

Sântana is located at around 20 km North-East of Arad city and 5 km East of the European route Arad-Oradea. The earth fortification is located 5.8 km South-West of the centre of Sântana in the direction of Zimandu Nou, on the left side of the road between the two settlements.

Fig. 3. Imagine din satelit a fortificaţiei (sursa Google Earth)/Satellite image of the earthwork (source Google Earth)

14

Istoricul cercetărilor

Prima reprezentare a fortificaţiei apare pe hărţile topografice iosefine (denumite după împăratul Iosif al II-lea de Habsburg) de la sfârşitul secolului al XVIII-lea (1782-1785). Astfel pe harta XXIV/XXX este schiţată destul de fidel incinta mare a fortificaţei, denumită alte Schanz şi un tumul de dimensiuni impresionante amplasat la extremitatea sudică a acesteia.

Proporţiile ciclopice ale acestei fortificaţii de pământ au atras atenţia diverşilor cronicari ai ţinutului arădean încă de la începutul secolului al XIX-lea. În descrierea geografică a comitatului Arad, Gábor Fábián aminteşte la 1835: un mare, vechi val, care îngrădeşte la vreo 50 de iugăre (1 iugăr=0.57 ha), numit Földvár sau Varba (Fábián 1835, 91). Medicul István Parecz scria în 1871 despre o întinsă ridicătură de pământ în hotarul Sântanei de forma unui castru roman, care în ciuda deselor arături este încă înaltă (Parecz 1871, 8, 19). János Miletz, prezentând în 1876 monumentele istorice şi arheologice din comitatele Timiş şi Arad, remarca descoperirea în preajma valului

The state of research

The earthwork is first mentioned on the Josephine topographic maps (named this way after the emperor Joseph II of Habsburg) in the 18th century (1782-1785). Thus, the map XXIV/XXX accurately displays the largest enclosure of the earthwork, named alte Schanz and a great-sized tumulus located on the Southern end of the complex.

The cyclopean dimensions of this earthwork came under the attention of different chroniclers of Arad region ever since the 19th century. In 1835, in his geographical account of the Arad County, Gábor Fábián acknowledged: a great, old earthen vallum, enclosing around 50 iugăre (1 iugăr=0.57 ha), named Földvár or Varba (Fábián 1835, 91). The physician István Parecz wrote in 1871 about

a big mound of earth on Sântana border, shaped like a Roman castrum, which had a significant height, despite the frequent ploughing (Parecz 1871, 8, 19). During the presentation of historical and archaeological monuments from Timiş and Arad Counties in 1876, János Miletz

Fig. 4. Hartă de la sfârşitul secolului al XVIII-lea cu localizarea fortificaţiei/XVIIIth century map locating the earthwork

15

de pământ de la Sântana a unor: bile de praştie din pământ ars de culoare roşiatică (Miletz 1876, 166-167).

Prima descriere mai amplă a acestui monument arheologic, însoţită de consideraţii istorice, este oferită în 1882 de către istoriograful Sándor Márki (Márki 1882, 112-121; Márki 1884, 185-194). Márki este primul care identifică această fortificaţie cu un ring avar. După fixarea poziţiei topografice a obiectivului, Márki pomeneşte faptul că incinta de formă ovală a ringului este tăiată de linia căii ferate, o treime rămânând la nord-est iar două treimi la sud-est de terasament. De asemenea mai menţionează că pe porţiunea valului circular, la nord-vest de calea ferată, în apropierea şoselei Sântana-Zimandu Nou, este aşezat un obelisc, folosit ca punct trigonometric militar. Anterior, pe harta iosefină, aici ar fi existat o Wirthshaus an der Schanz. Lui Márki nu i-a scăpat nici faptul că pe latura opusă, cea de sud-est, în afara valului circular se află o movilă numită Földvár sau Varba (Márki 1882, 112). După părerea lui Márki diametrul ringului mare ar măsura aproximativ 2 km, iar cel mic puţin peste 1 km. Suprafaţa o calculează la aproximativ 353 iugăre cadastrale, adică 203 hectare (Márki 1882, 113). În apropierea obeliscului, coama valului măsura pe atunci (1882) 4 m, iar pe fiecare latură panta corespunzătoare avea 19 m. Márki ne mai informează că şanţul exterior al valului nu se mai vede aproape deloc, în schimb şanţul interior avea dimensiuni considerabile (Márki 1882, 113).

Vorbind despre pământul ars care se poate observa pe suprafaţa ringului, Márki aminteşte că la tăierea

mentioned the discovery of sling projectiles made of reddish burned earth, next to the earthen vallum from Sântana (Miletz 1876, 166-167).

The first extensive description of that archaeological monument, accompanied by historical accounts, was made in 1882 by historian Sándor Márki (Márki 1882, 112-121; Márki 1884, 185-194). Márki was the first one to identify this earthwork as an Avar ring. After establishing the topographic layout of the site, Márki mentioned that the oval shaped enclosure of the ring was divided in two by the railway route; one third of the enclosure was on the North-East and two thirds were located on the South-East of the railway bank. He also mentioned that an obelisk, used as a military trigonometric checkpoint, was placed on the circular area of the earthen vallum, North-West of the railway, close to the road linking Sântana to Zimandu Nou. Previously, the Josephine map recorded a Wirthshaus an der Schanz on that location. Márki also noticed that on the opposite side, on the South-East, outside the circular earthen vallum, there was a mound of earth named Földvár or Varba (Márki 1882, 112). According to Márki, the big ring had around 2 km in diameter, while the small ring had a little over 1 km in diameter. The total surface area estimated by Márki summed around 353 iugăre, which is 203 ha (Márki 1882, 113). At that time (1882), the earthen vallum crest near the obelisk was 4 m high, and the slope on each side was 19 m long. Márki also informed us that the exterior ditch was not visible anymore, but the interior ditch size was considerable (Márki 1882, 113).

16

în două locuri a valului circular, cu ocazia construirii căii ferate, s-a constatat că pământul ars din interiorul valului măsura aproximativ 0,50-0,60 m grosime. Bulgări de chirpici, dar şi fragmente ceramice, au fost culese mai ales de-a lungul valului. În acelaşi an Márki a donat chirpiciul şi fragmentele ceramice colectate de la faţa locului colecţiei de antichităţi a liceului de băieţi din Arad (Barbu et alii 2002, 487, nr. crt. 133-140).

Cu toate rezervele pe care le invocă uneori, Márki atribuie fortificaţia de la Sântana avarilor. În sprijinul afirmaţiei sale se foloseşte şi de valurile de pământ ce trec pe la vest şi est de fortificaţie, considerând valul dinspre vest, numit de localnici Traianul sau Ördögárka, de provenienţă avară, iar valurile dinspre est drept şanţuri romane folosite de către avari. În expunerea sa, Márki se ocupă şi de tell-ul Dâmbul Popilor/Papokhalma/Holumb situat la 4,65 km nord-vest de fortificaţie. Descoperind pe suprafaţa acestui tell fragmente ceramice şi chirpici, Márki îl consideră drept un bastion înaintat al acestui ring avar (Márki 1882, 115-118).

Din păcate Márki nu publică în lucrarea sa fotografii, desene ale pieselor găsite ori schiţe ale fortificaţiei. Pentru a fundamenta părerea sa despre originea avară a fortificaţiei, o aseamănă cu cea de la Corneşti Iarcuri, pe care József Péch o declarase deja avară, aşa cum vom vedea mai jos (Péch 1877). Urmând metodele, cu precădere lingvistice, ale investigaţiei lui Péch, Márki operează în sprijinul teoriei sale cu presupuse toponime de origine avară ale unor localităţi

Referring to the visible burned earth on the surface of the ring, Márki reminded that cutting the circular ring in two different areas, when the railroad had been built, revealed the thickness of the burned earth inside the ring, which was 0.50-0.60 m thick. Adobe bricks, as well as pottery remnants were found along the earthen vallum. On the same year, Márki donated the adobe and the pottery collected on site to the Antiquity Collection of the Boys Highschool from Arad (Barbu et alii 2002, 487, no. 133-140).

Despite the doubts expressed from time to time, Márki assigned the earthwork from Sântana to the Avars. He supported his theory by referring to the earthen vallums stretching to the West and to the East of the earthwork. In his opinion, the Western earthen vallum, named Traianul or Ördögárka by the locals, had an Avar origin, while the Eastern earthen vallums were Roman ditches used by the Avars. Márki’s paper also talked about Dâmbul Popilor/Papokhalma/Holumb tell, located 4.65 km North-West of the fortification. The discovery of pottery fragments and adobe on the tell surface, determined Márki to record the tell as an outwork stronghold of that Avar ring (Márki 1882, 115-118).

Unfortunately, Márki didn’t include photographs in his paper, nor drawings of the artefacts or sketches of the earthwork. He supported his opinion regarding the Avar origin of the earthwork, by comparing it with the earthwork from Corneşti Iarcuri, which had already been classified as an Avar structure by József Péch, as

17

din comitatul Arad: Zimánd, Simánd, Varsánd, Zaránd. Păstrând totuşi conduita ştiinţifică afirmă că: e mai bine totuşi să mă îndepărtez de terenul alunecos al etimologiei (Márki 1882, 121).

În primul volum al monografiei sale istorice privind comitatul Arad, Márki îşi menţine părerea cu privire la originea avară a fortificaţiei de la Sântana. În această lucrare repetă în fond datele principale pe care le publicase anterior. Ca o noutate atribuie ipotetic tot avarilor şi podoabele de aur descoperite cu ocazia modificărilor de terasament ale căii ferate din anul 1888 (Márki 1892, 39-40).

Podoabele de aur fuseseră descoperite în primăvara anului 1888 de către lucrătorii ce amenajau terasamentul căii ferate Arad-Oradea. În şanţul din faţa valului aceştia au descoperit un vas din pastă grosieră, cu oase umane şi un tezaur compus din 23 de piese din aur. Alături a mai apărut un mormânt de înhumaţie, cu scheletul dispus în poziţie chircită, fără inventar. Săpăturile de salvare întreprinse de către Aurel Török au mai dezvelit un mormânt de copil şi unul de adult, fără inventar arheologic. Majoritatea pieselor din tezaur au ajuns în primă instanţă la conducerea căilor ferate, ca în cele din urmă să fie achiziţionate de Muzeul Naţional Maghiar din Budapesta (Dörner 1960, 471-479; Mozsolics 1973, 208, Taf. 104-105).

De la Márki şi până la mijlocul secolului al XX-lea nici un alt specialist nu s-a mai ocupat, în mod serios, de fortificaţia de la Sântana. Cu tot îndemnul Societăţii

explained herein below (Péch 1877). Following Péch’s methods of investigation (mainly linguistic methods), Márki sustained his theory by using toponyms of Avar origin of several settlements from Arad County: Zimánd, Simánd, Varsánd, Zaránd. Nevertheless, he preserved the scientific approach and declared: it’s better to stay away from the slippery grounds of etymology (Márki 1882, 121).

Márki maintained his opinion regarding the Avar origin of the earthwork from Sântana in the first volume of his historical monograph of Arad County. Actually, he reasserted the main scientific data published previously. Additionally, he assigned the golden jewellery discovered during the 1888 railway works to the Avars, too (Márki 1892, 39-40).

The golden jewelleries were discovered in spring 1888 by the workers employed to develop the railway between Arad and Oradea. The workers found a vessel made of coarse-grained material containing human bones and a treasure consisting of 23 golden pieces. An inhumation grave was discovered nearby, containing a crouched skeleton, with no inventory. The rescue excavations undertook by Aurel Török revealed a child tomb and an adult tomb, with no archaeological inventory. The railway managing board took possession of most of the treasure pieces, but eventually they were purchased by the National Hungarian Museum from Budapest (Dörner 1960, 471-479; Mozsolics 1973, 208, Taf. 104-105).

Since Marki’s research, until the middle of the

18

arheologice de la Budapesta, adresat la 1895 conducerii Societăţii Culturale Kölcesy din Arad, nu s-a efectuat nici o săpătură arheologică în acest sit. În 1942 Constantin Daicoviciu, directorul de atunci al Institutului de Arheologie din Cluj-Napoca, împreună cu Nicolae Covaciu, directorul Muzeului din Arad, au intenţionat să efectueze săpături arheologice la movilele de la Glogovăţ şi la fortificaţia de la Sântana, dar din motive financiare planul nu a mai putut fi pus în practică.

În anul 1949 Dorin Popescu, alături de colectivul şantierului arheologic însărcinat cu studiul graniţei de vest a Daciei şi traiului populaţiei barbare, şi-a propus să facă şi el săpături la ringul avar de la Sântana (Popescu et alii 1950). În urma prelungirii investigaţiilor de la Vărşand nu a mai rămas însă timp suficient şi pentru alte cercetări (Raportul Nr. 271/1952 privind Cercetările arheologice efectuate în raionul Criş, întocmit de Egon Dörner; arhiva Secţiei de Arheologie a Complexului Muzeal Arad).

middle of the 20th century, no other specialist took interest in the earthwork from Sântana. Despite the recommendation sent by the Archaeological Society from Budapest in 1895 to the Kölcesy Cultural Society from Arad, no further a r c h a e o l o g i c a l investigations were conducted on this site. In 1942, Constantin Daicoviciu, director

of the Institute of Archaeology from Cluj-Napoca, together with Nicolae Covaciu, director of the Museum from Arad, expressed their intention to conduct archaeological excavations on the Glogovăţ mounds and the earthwork from Sântana, but the plan was no longer put into practice for lack of financial resources.

In 1949, Dorin Popescu, together with the team of archaeologists in charge of studying the Western border of Dacia and the life of Barbarian population, also intended to perform archaeological diggings on the Avar ring from Sântana (Popescu et alii 1950). Unfortunately, due the delay of the excavations from Vărşand, there was not

Fig. 5. Piese de aur din tezaurul descoperit în 1888/Gold artifacts from the hoard discovered in 1888

19

Fig. 6. Solicitare a Muzeului Naţional Maghiar către conducerea căilor ferate în vederea achiziţionării tezaurului descoperit în 1888/Hungarian National Museum’ s request to the Railways Department regarding the acquisition of the hoard discovered in 1888

Fig. 7. Îndemnul Societăţii arheologice de la Budapesta către Societatea culturală Kölcesy pentru efectuarea de săpături la Sântana/The advice of the Budapest Archaeological Society for the Köl- cesy Cultural Society to carry out excavations at Sântana

20

Curentul istoriografic ce atribuia avarilor fortificaţia de la Sântana avea să se schimbe în urma unei cercetări de teren efectuate de către Egon Dörner şi Mircea Rusu în primăvara anului 1952. Din arhivele Muzeului din Arad aflăm că: În ziua de 3 mai, în colaborare cu tov. Rusu Mircea, asistent la Muzeul Academiei – Cluj, am cercetat începând de la orele 7 dimineaţa aşa-zisul „Ring Avar”, situat la 6 km S-V de comuna Sântana. După fragmentele ceramice, chirpiciu şi percutoare găsite cu ocazia diferitelor sondajii intreprinse, am ajuns la concluzia că această aşezare întărită de proporţii considerabile – diametrul cercului exterior al fortificaţiei măsurând peste 1 km! – poate fi datată din epoca bronzului, având astfel o vechime de peste 3.500 ani ... Această cetate de pământ constituită din două cercuri concentrice, cel interior necomplet înspre S-E, ambele înconjurând o ridicătură în formă de movilă, care pare a fi centrul fortificaţiei. În afara zidului exterior, format în majoritate din pământ ars, tot în direcţia S-E se află o movilă depăşind ca mărime toate celelalte – probabil un turn exterior de apărare şi observaţie. În afara fortificaţiei mai sunt două movile mai teşite, după toate probabilităţile – tumuli (Fragment din Raportul Nr. 271/1952 privind Cercetările arheologice efectuate în raionul Criş, întocmit de Egon Dörner).

Un an mai târziu, în 1953, acelaşi Egon Dörner este delegatul muzeului arădean în vederea efectuării unor noi cercetări la fortificaţia de pământ de la Sântana. Dörner era însărcinat să ia legătura cu responsabilii şantierului de construcţii C.F.R., care efectuau lucrări în raza sitului, pentru a se asigura salvarea oricăror obiecte istorice găsite cu

enough time left for other researches (Report no. 271/1952 regarding the Archaeological researches conducted in the Criş district, submitted by Egon Dörner; the archives of the Archaeology Department of the Museum Arad).

The historiographic trend ascribing the earthwork from Sântana to the Avar people was about to change, as a result of the field research conducted by Egon Dörner and Mircea Rusu in the spring of 1952. According to the archives of the Museum Arad: on May 3rd, at 7 o’clock in the morning, together with comrade Rusu Mircea, assistant at the Academy Museum – Cluj, I initiated the research of the so called „Avar Ring”, a site located 6 km South-West of Sântana. The pottery, adobe or bolts discovered during various archaeological investigations, have led us to the conclusion that this fortified settlement of such great amplitude – the diameter of the outer compound of the earthwork measures over 1 km! – may be dated back to the Bronze Age, which means over 3500 years old... This earth fortress is made out of two concentric compounds, the interior compound still unfinished on the South-East end, but both enclosing a mound, which seems to be the centre of the earthwork. Outside the outer wall made out of burned earth, to the South-East, there is an earth mound, towering over the other mounds – most probably an exterior defence and surveillance tower. Outside the earthwork two other mounds can be observed, of lower altitude, most probably – tumuli (fragment from the Report no. 271/1952 regarding the Archaeological researches conducted in the Criş District, submitted by Egon Dörner).

One year later, the same Egon Dörner was the

21

ocazia săpăturilor...(Delegaţia Nr.739/1953/Complexul Muzeal Arad). Câţiva ani mai târziu acelaşi Egon Dörner împreună cu Nicolae Kiss recuperează din spatele fostei halte C.F.R. Cetatea Veche, şase proiectile (bile) de praştie din lut care vor intra în colecţiile Muzeului din Arad (nr. inv. 13.456-13461). Alte trei asemenea piese vor ajunge în colecţia şcolii nr. 1 din Sântana (Mureşan 2007, 120, n. 5).

În acest context trebuie menţionat şi articolul lui E. Dörner privind tezaurul de aur din 1888. Este vorba de

Fig. 8. Imagine dinspre nord a incintei III/Northen view of the third enclosure

Fig. 9. Fragmente ceramice descoperite de către E. Dörner/Pottery fragments discovered by E. Dörner

delegate of the Museum Arad for carrying out new research activities on the earthwork site from Sântana. Dörner was instructed to get in contact with the people responsible for the construction site of C.F.R. (Romanian Railway Company), who were performing construction works in the vicinity of the archaeological site, in order

to ensure the rescue of any historical objects discovered during the excavations works... (Delegation No. 739/1953/Museum Arad). Several years later, Egon Dörner together with Nicolae Kiss managed

Fig. 10. Fragmente ceramice descoperite de către E. Dörner/ Pottery fragments discovered by E. Dörner

22

primul studiu care oferă informaţii detaliate cu privire la piesele găsite atunci şi care propune o încadrare cronologică pertinentă a descoperirilor – perioada târzie a epocii bronzului (Dörner 1960).

Ca urmare a noilor interpretări cronologice ale fortificaţiei de pământ, în vara anului 1963 un colectiv de arheologi, format din Mircea Rusu (Institutul de Arheologie din Cluj), Egon Dörner (Muzeul Judeţean Arad), Ivan Ordentlich şi Sever Dumitraşcu (Muzeul Ţării Crişurilor Oradea), şi-a propus o amplă sondare a sitului. Mai bine de 30 de ani rezultatele cercetărilor lor nu au fost publicate, frânturi de informaţii, privind dimesiunile fortificaţiei, descoperirile şi datarea sa, strecurându-se într-o serie de publicaţii care tratau problematica perioadei târzii a epocii bronzului din zonă (Rusu 1963, 188-189; Horedt 1967, 141, 149-150; Rusu 1969, 1298; Rusu 1973, 109, fig. 1/8; Horedt 1974, 224, nr. 19; Dörner 1976, 42-44; Rusu 1979, 119, 121, Mărghitan 1993, 35-40).

Din raportul apărut în 1996 în Ziridava, anuarul Muzeului din Arad (Rusu et alii 1996), dar şi în limba germană într-un volum omagial dedicat amintirii profesorului Kurt Horedt (Rusu et alii 1999), aflăm că în 1963 au fost trasate două secţiuni şi două casete, fără a se putea preciza suprafaţa exactă a acestora. Prima secţiune a avut ca scop investigarea sistemului de fortificare nordic al incintei B (cea mai mare, incinta III după noi), cea de-a doua a fost trasată pe valul incintei A (incinta I după noi), iar cele două casete au fost deschise tot în

to recover from behind the former C.F.R. train stop Cetatea Veche six sling-projectiles made of clay, which became part of the Museum Arad Collections (inv. no. 13.456-13461). Other three similar objects were included in the collection of Sântana School no. 1 (Mureşan 2007, 120, n. 5).

In this context, we must take into consideration the article written by Egon Dörner on the golden treasure from 1888. This is the first paper giving detailed information regarding the artefacts discovered at that time and also the first paper suggesting a relevant chronologic classification of the archaeological discoveries – late Bronze Age (Dörner 1960).

As a consequence of the new chronologic interpretation of the earthwork, in the summer of 1963, a team of archaeologists, including Mircea Rusu (the Institute of Archaeology from Cluj), Egon Dörner (The Museum of Arad County), Ivan Ordentlich and Sever Dumitraşcu (The Museum “Ţara Crişurilor” of Oradea), embarked on a large scale investigation of the site. For more than 30 years the results of their research were not published; bits of information regarding the earthwork amplitude, the discoveries and the historical dating of the site worked their way inside various publications dealing with the late Bronze Age issues of that geographical region (Rusu 1963, 188-189; Horedt 1967, 141, 149-150; Rusu 1969, 1298; Rusu 1973, 109, fig. 1/8; Horedt 1974, 224, nr. 19; Dörner 1976, 42-44; Rusu 1979, 119, 121, Mărghitan 1993, 35-40).

23

interiorul incintei A. În urma săpăturilor s-a constatat existenţa unui nivel cu materiale ce aparţine epocii timpurii a cuprului (cultura Tizsápolgar, cca. 4500 - 4300-4200 a.Chr.). De asemenea a fost descoperit şi un mormânt de înhumaţie, în poziţie chircită, aparţinând acestor comunităţi. Pe lângă materialele Tizsápolgar au apărut fragmente ceramice specifice epocii târzii a bronzului şi primei epoci a fierului (sec. XIII-X a.Chr.). În opinia lor prima fortificaţie (incinta A) a fost ridicată în prima fază a epocii fierului (Ha A1), celelalte două fiind ulterioare. În secţiunea I a fost dezvelit un alt mormânt de înhumaţie, care pe baza inventarului funerar ar fi aparţinut fazei Ha B a primei epoci a fierului. Cu toate că săpăturile din 1963 depăşeau 400 m2, tabloul cronologic şi cultural al acestui sit era departe de a fi lămurit. Autorii acestor cercetări nu au putut să exploateze informaţiile oferite de o fotografie aeriană făcută de Alexandru Ştefan în anul 1965 şi care surprindea mult mai exact toate elementele de fortificare. Ea a fost publicată abia în 1999 şi este extrem de utilă pentru reconstituirea unor realităţi din teren după 45 de ani de arături intense şi implicit de distrugere treptată a valurilor de pământ (Stefan 1999, 264, fig. 1-2).

Începând cu anii ‘60 ai secolului trecut, pe suprafaţa fortificaţiei de pământ de la Sântana au mai fost descoperite şi alte artefacte interesante, care completează imaginea noastră asupra acestui obiectiv arheologic. Astfel, în 1954 Ioan Mărinoiu a găsit, în urma unor lucrări agricole, un celt şi un fragment de seceră, care au intrat în colecţiile muzeului arădean. Tot în această perioadă

According to the report published in 1996, in Ziridava, the annual publication of the Museum Arad (Rusu et alii 1996), as well as in a German language publication, issued in memory of prof. Kurt Horedt (Rusu et alii 1999), we learned that in 1963 two trenches and two grid squares had been marked out, without any record of their exact size. The first section was aimed at studying the Northern earthwork system of enclosure B (the biggest, enclosure III), the second was traced on the earthen vallum of enclosure A (enclosure I), and the two grid squares were laid out inside the enclosure A. The excavations executed in the area unveiled the existence of a layer containing materials belonging to the Early Copper Age period (Tizsápolgar culture, around 4500 – 4300-4200 BC). It was also discovered an inhumation grave, in crouched position, belonging to those communities. Besides the Tizsápolgar materials, there were findings of ceramic artifacts specific for the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age (13th-10th century BC). In their opinion, the first earthwork (enclosure A) was raised in the first stage of the Iron Age (Ha A1), followed by the other two. Trench I uncovered another inhumation grave, and according to the grave inventory it belonged to the Ha B phase of the Early Iron Age. Regardless of the great extent of the 1963 excavation works, spread on over 400 sqm of land area, the chronological and cultural context of that site was far from being fully comprehended. The researchers were not able to explore the information supplied by the aerial photograph taken by Alexandru Ştefan in 1965,

24

a mai fost descoperit întâmplător un brâu realizat din bronz aurit, care a fost achiziţionat de Muzeul Naţional Brukhental din Sibiu (Rusu et alii 1996, 22, nota 2). În anul 1976 tractoristul Aurel Bulzea din Sântana ar fi deranjat, tot în spatele fostei halte C.F.R. Cetatea Veche, un cuptor plin (circa 200 de piese!) cu proiectile (bile)

Fig. 11. Fragmente ceramice descoperite în săpăturile din 1963/ Pottery fragments discovered in 1963’s excavation

Fig. 12. Fragmente ceramice descoperite în săpăturile din 1963/ Pottery fragments discovered in 1963’s excavation

which offered an improved image of all the earthwork elements. The photograph was published in 1999 and it was extremely useful for recomposing the land features after 45 years of intense ploughing and inherent gradual destruction of the earthen vallums (Ştefan 1999, 264, fig. 1-2).

25

de praştie din lut (Mureşan 2007, 120, n. 7, 121). Elevii cercului de istorie-arheologie de la Şcoala generală nr. 1 din Sântana, îndrumaţi de Augustin Mureşan, urmărind lucrările la un canal care a traversat fortificaţia, au salvat în 1980 mai multe obiecte: un topor din piatră găurit şi şlefuit, proiectile (bile) de praştie din lut, două râşniţe din piatră, două greutăţi de la războiul de ţesut, ceramică şi un fragment dintr-un tipar din gresie probabil pentru turnarea unor piese de harnaşament (Mureşan 2007, 120, n. 8). O altă descoperire a survenit în 1982 când Augustin Mureşan a recuperat de la un alt tractorist două brăţări decorate din bronz (Mureşan 1987). În 1997 G. Ciaciş donează Complexului Muzeal Arad şapte piese de bronz, şase fragmente de seceri şi o turtă de bronz. În timpul cercetărilor magnetometrice desfăşurate în primăvara anului 2008 a fost descoperit un pandantiv, un fragment de brâu şi un fragment de cuţit, toate confecţionate din bronz. Tot în cursul anului 2008, Lucian Mercea a găsit, în urma unor cercetări de suprafaţă, două fragmente de brâie de bronz, un fragment de tablă şi unul de bandă, tot din bronz. La începutul anului 2009, într-o cercetare efectuată de acelaşi Lucian Mercea, au mai fost identificate o verigă şi un fragment de pumnal din bronz.

Noile cercetări

Intenţia de a relua cercetările la fortificaţia de pământ de la Sântana, aşa cum spuneam, a început să se concretizeze în primăvara anului 2008. Specialiştilor

After the 1960s, other interesting artifacts were discovered at the earthwork from Sântana, adding the finishing touches to our present day picture of that archaeological site. Thus, in 1954, following some agricultural works carried on in that area, Ioan Mărinoiu found a socketed axe and a sickle fragment, which were included in the collections of the Museum Arad. An accidental discovery of a golden bronze belt was made in the same period, and the piece was purchased by the Bruckhental National Museum from Sibiu (Rusu et alii 1996, 22, note 2). In 1976, Aurel Bulzea, a tractor driver from Sântana, disturbed an oven filled (around 200 pieces!) with clay sling-projectiles, located behind the same former C.F.R. train stop Cetatea Veche (Mureşan 2007, 120, n. 7, 121). In 1980, the students from the History and Archaeology Club of the Secondary School no. 1 from Sântana, under the guidance of Augustin Mureşan, surveyed the construction works of a canal crossing the fortification area and rescued several objects: a polished and drilled stone axe, clay sling-projectiles, two stone grinders, two loom weights, ceramic objects and a fragment of a sandstone mould, probably used for casting harness parts – tutuli (Mureşan 2007, 120, n. 8). Another discovery was made in 1982, when Augustin Mureşan retrieved two decorated bronze bracelets from another tractor driver (Mureşan 1987). In 1997 G. Ciaciş made a donation to the Museum Arad, comprising seven bronze pieces, six sickle fragments and a bronze rounded ingot. The magnetometric researches conducted in spring 2008

26

Fig. 13. Artefacte de bronz descopertire pe suprafaţa fortificaţiei/ Bronze Artifacts discovered on the surface of the earthwork

Fig. 14. Artefacte de bronz descopertire pe suprafaţa fortificaţiei/ Bronze Artifacts discovered on the surface of the earthwork

Fig. 15. Artefacte de bronz descopertite pe suprafaţa fortificaţiei/Bronze Artifacts discovered on the surface of the earthwork

27

români de la Complexul Muzeal Arad, Academia Română (Institutul de Arheologie şi Istoria Artei din Cluj), şi Universităţii de Vest din Timişoara, li s-a alăturat o echipă germană de la Universitatea din Bochum, cooptată în vederea efectuării unor cercetări magnetometrice. Acest tip de cercetare a dus la identificarea într-un timp relativ scurt a unor structuri, cum ar fi primele două valuri, şanţurile şi palisadele (structura defensivă a fortificaţiei), un drum situat în interiorul fortificaţiei şi numeroase construcţii de suprafaţă sau gropi.

Cercetarea arheologică din toamna anului 2009 a avut ca scop stabilirea coloanei stratigrafice a sitului, studierea sistemului de fortificare, recuperarea tuturor informaţiilor şi contextelor arheologice identificate pe sectorul ce urma a fi afectat de introducerea unei

Fig. 16. Fotografie din timpul cercetării magnetometrice/ Photography taken during the magnetometric research

revealed a pendant, a belt fragment and a knife fragment, all made of bronze. Also, surface investigations carried out by Lucian Mercea in the same year unveiled two bronze belt fragments, a tablet fragment and a band fragment made of bronze. At the beginning of 2009 the same Lucian Mercea discovered a chain link and a bronze dagger fragment.

The new researches

As mentioned earlier, the intention to resume the research of the earthwork from Sântana, began to gain shape in spring 2008. The team of Romanian specialists from Arad Museum, the Romanian Academy (the Institute of Archaeology and History of Art from Cluj) and the West University of Timişoara, was joined by a German team from the University of Bochum, invited for the purpose of conducting magnetometric scanning. In a very short period of time, that type of research led to the identification of new structures, such as the first two earthen vallums, the defence ditches and palisades (the defensive structure of the fortification), a road inside the fortification and multiple surface buildings or pits.

The goal of the archaeological research carried on in the autumn of 2009, was to establish the stratigraphic profile of the site, to study the earthwork structure, to recover all the data and archaeological context identified in the section area where the future gas pipeline was to be assembled (Hügel et alii 2010).

28

magistrale de gaz (Hügel et alii 2010). În acest scop au fost trasate trei secţiuni: S 01, S

02, S 03. Secţiunea S 01 a avut dimensiunile iniţiale de 80x4 m, fiind lărgită ulterior până la 6,50 m, în faţa şi în spatele valului de pământ. S 02 a avut iniţial aceleaşi dimensiuni cu S 03: 10x1,5 m. Pentru a dezveli în întregime complexele Cx 02 şi Cx 03 din S 02 au fost deschise două casete. În dreptul Cx 02 a fost trasată o casetă de 2,3x1 m, iar în dreptul Cx 03 o alta de 2x1 m. Dezvelirea integrală a complexului denumit de noi Cx 04, situat în secţiunea S 03, a necesitat prelungirea secţiunii cu 1,5 m şi lărgirea ei pe acest tronson cu 2 m. Întreaga suprafaţă cercetată în 2009 a fost de 453,5 m 2.

I n v e s t i g a ţ i i l e arheologice au scos la lumină sistemul de fortificare a celei de-a treia incinte. Datarea acestei cetăţi de pământ la sfârşitul epocii bronzului a fost asigurată de descoperirea în interiorul şanţului de apărare a unui vas întregibil.

To this end, three trenches were laid out: S 01, S 02, S 03. The original dimensions of S 01 were 80x4 m, but it was extended later on up to 6.50 m, in front and behind the earthen vallum. S 02 and S 03 had the same dimensions: 10x1.5 m. In order to fully reveal the archaeological complexes Cx 02 and Cx 03 from S 02, two grid squares were opened. A grid square of 2.3x1 m was delimited on top of Cx 02 and another one measuring 2x1 m on top of Cx 03. The full uncovering of the Cx 04

complex, located in S 03, required the extension of S 04 by 1.5 m in length and 2 m in width. The entire surface under investigation in 2009 reached 453.5 sqm. The archaeological researches exposed the earthwork structure of the third enclosure. The earth fortress could be assigned to the end of the Bronze Age, thanks to the discovery of a complete vessel inside the defence ditch. Additionally, the layers making up the earthen vallum unveiled Fig. 17. Planul săpăturii, campania 2009/Excavation plan, 2009 campaign

29

Pe lângă aceasta, în lentilele de pământ din care a fost realizat valul, au apărut fragmente ceramice, vase întregi şi obiecte de metal, toate aparţinând aceleiaşi perioade târzii a epocii bronzului. Cea de-a treia fortificaţie, cea mai impresionantă ca mărime de la Sântana, a suprapus o aşezare de la finalul epocii cuprului, ce poate fi atribuită aşa-numitei culturi Baden (circa 3000 a.Chr.). Pe tronsonul celor trei secţiuni au fost identificate 40 de complexe arheologice.

Descrierea sistemului de fortificare

După cum am precizat mai sus, scopul principal al cercetărilor arheologice din anul 2009 a fost acela de a sonda sistemul de apărare a celei de-a treia incinte. Pentru aceasta a fost trasată secţiunea S 01, care a tăiat valul şi şanţul. Secţiunea a fost orientată NEE-SVV. În spatele fortificaţiei, din dreptul caroului 0 şi până în dreptul caroului 33, s-a identificat un şanţ de scoatere a pământului pentru ridicarea valului, şanţ al cărei adâncime maximă a fost de 2,06 m. Ridicarea valului fortificaţiei a necesitat, pe lângă pământul scos din şanţul de apărare şi dislocarea din interiorul fortificaţiei a unei mari cantităţi de pământ.

Valul de pământ este foarte bine păstrat şi are dimensiuni impresionante: o lăţime de 26,82 m şi o înălţime 2,44 m. Modalitatea de a ridica valul a fost foarte complexă, constând din două unităţi arhitectonice. Prima este reprezentată de miezul valului, o construcţie

ceramic fragments, complete vessels and metal objects, all of them belonging to the same late Bronze Age. The third enclosure, the most ample sized structure from Sântana, overlapped a settlement from the end of the Copper Age period, which may be allocated to the so called Baden culture (around 3000 BC). Forty archaeological complexes could be identified in the archaeological corridor of the three trenches.

The description of the earthwork structure

As we mentioned in the paragraphs above, the main goal of the 2009 archaeological research activities was to investigate the defence system of the third enclosure. For this purpose, we traced trench S 01, cutting the wave and the ditch. The trench had a NEE-SWW orientation. Behind the earthwork, from grid square 0 to grid square 33, we were able to identify a ditch for earth displacement meant for raising the earthen vallum, a ditch that had a maximum depth of 2.06 m. In addition to the earth displaced from the defensive ditch, the earthen vallum elevation also required the dislocation of a large quantity of earth from inside the fortification.

The earthen vallum is very well preserved and has impressive dimensions: a width of 26.82 m and a height of 2.44 m. The method used for raising the earthen vallum was very complex, and consisted of two architectural units. The first one is the earthen vallum core, a construction with a 14 m wide baseline and a 10.40 m width on the

30

lată la bază de 14 m, iar la suprafaţă de 10,40 m. Această unitate a fost ridicată pe un pat de bârne, având rolul de fundaţie a construcţiei. Patul de bârne a fost dublat de un nivel de pietre de carieră, ambele fiind acoperite cu lentile de pământ bătut. Miezul valului, a fost îmbrăcat într-un strat de lut galben, gros de aproximativ 5 cm, care a avut rolul de a etanşeiza construcţia. Acestui miez i-au fost adăugate, înspre interiorul fortificaţiei, lentile groase de pământ bătut, cu scopul de a solidifica valul. Ele reprezintă cea de-a doua unitate constructivă.

Acolo unde ne aşteptam să găsim palisada de lemn,

Fig. 18. Valul şi rămăşiţele zidului de lut, la conturare/The earthen vallum and the remains of the wall, at the outlining

surface. This unit was raised on a wood beam bed, acting as the foundation of the structure. The beam bed was strengthened by a quarry stone layer, both being covered by battered earth. The earthen vallum core was encased in a yellow clay mantle, around 5 cm thick, intended to isolate the structure. Thick layers of battered earth were added to the earthen vallum core, towards the interior of the earthwork, in order to strengthen the earthen vallum. Those layers represent the second constructive unit.

To our surprise, the place where we were expecting to find the wooden palisade, indispensable for the

31

Fig. 19. Lentilele de pământ bătut/Subsequent loops of battered earth

Fig. 21. Vedere dinspre interior a miezului valului/Rear view of the earthen vallum core

Fig. 20. Detaliu cu miezul valului de pământ văzut dinspre interior/Rear part of the earthen vallum core-detail

Fig. 22. Profilul nordic al valului/The Northern profile of the earthen vallum

32 Fig. 23. Buştenii de la baza miezului valului/The logs

form the base of the earthen vallum core

Fig. 25.Fotografie a miezului valului/ Photography of the earthen vallum core

Fig. 24. Profilul sudic al valului/The Southern profile of the earthen vallum

33

fără de care valul nu ar fi avut rolul funcţional pentru care a fost ridicat, am avut surpriza să descoperim un zid din lut. El s-a conturat ca o grupare masivă formată din bulgări de lut ars. Structura sa a constat din trei rânduri de pari, relativ paraleli, legaţi cu nuiele, spaţiul delimitat astfel fiind umplut cu bulgări de lut (aşa cum se construiesc şi astăzi casele din chirpic). Mulţi dintre aceşti vălătuci mai păstrau încă amprenta degetelor celor care i-au frământat. Astfel a fost ridicat un zid care s-a mai păstrat pe o înălţime de circa 40 de cm şi o grosime de aproximativ 80 cm. Dacă partea interioară nu a fost finisată, lăsându-se netencuită structura de lemn, la exterior am constatat că zidul a fost lutuit de cel puţin cinci ori. Mai multe proiectile (bile) de praştie, confecţionate dintr-un lut foarte bine ars, au fost găsite in situ pe partea exterioară a zidului. Ele sugerează indubitabil că o bună parte din acesta a fost distrus de un adevărat foc de artilerie. Un incendiu violent a cuprins întreaga structură, căpătând astfel consistenţa care a făcut-o să se păstreze până astăzi.

Şanţul de apărare are o deschidere maximă de 10,20 m şi o adâncime de 2,86 m de la nivelul de amenajare. El a fost săpat în formă de V, cu latura exterioară mai

functional role of the earthen vallum, was occupied by a clay wall. The wall emerged as a solid group made of burned clay clods. Its structure consisted of three relatively parallel rows of poles, linked together with twigs. The space within that frame was filled with clay clods (similar to the present day construction method used for adobe houses). Many wattles preserved the trace of the fingers which squeezed them. That was the method used to raise the wall, which is now reduced to about 40 cm high and 80 cm thick. The interior side of the wall was not smoothed, the wooden structure being left unplastered, but the exterior side of the wall was loamed at least five times. Several sling-projectiles, made of burnt clay, were found in situ, on the outside of the wall. That was a clear and undisputable proof that a considerable portion of

the wall was destroyed by a real artillery fire. The violent fire that engulfed the entire structure rendered the wall’s density which preserved until the present day.

The defensive ditch has an opening of 10.20 m and a depth of 2.86 m from the embankment level. The ditch is a V shaped excavation, the exterior slope being steeper than the slope located at the base of the Fig. 26. Rămăşiţele arse ale zidului de lut/Burned remains of the wall

34

Fig. 27. Zidul de lut la conturare, vedere dinspre interior/The outlining of the wall, view fron inside

Fig. 28. Zidul de lut la conturare, vedere dinspre exterior/The wall at the outlining, view from outside

Fig. 30. Detaliu cu latura exterioară a zidului de lut/Detail of outer side wall

Fig. 29. Proiectile (bile) de praştie/Sling projectiles

35

Fig. 31. Valul şi şanţul de apărare ale incintei III/The earthen vallum and the defense ditch of the enclosure III

Fig. 32. Fotografie a zidului de lut/Photography of the wall

36

puţin abruptă decât cea situată spre baza valului. Fundul şanţului este de formă aproximativ ovală, fiind mai ridicat înspre interiorul fortificaţiei. Şanţul a fost săpat direct în lutul galben, până s-a atins un nivel de lut galben-roşcat nisipos. În umplutura sa au apărut fragmente ceramice, un vas întregibil, numeroase fragmente de oase umane şi un corn întreg de cervideu. Diversele lentile de pământ demonstrează că şanţul a fost puternic colmatat încă înainte de incendierea valului. Cercetările de teren, dar şi studierea diferitelor hărţi, ne-au determinat să luăm în considerare şi posibilitatea devierii în şanţul de apărare a unui curs de apă. Astăzi se mai poate observa cum incinta a III-a barează, în apropierea săpăturii noastre, o veche albie de râu, pe care am şi identificat-o de altfel arheologic în spatele valului.

Dimensiunile estimative ale celor trei incinte

Pe baza măsurătorilor efectuate pe teren, a informaţiilor oferite de fotografiile aeriene şi a datelor furnizate de programul Google Earth, am putut calcula estimativ dimesiunile celor trei fortificaţii de la Sântana Cetatea Veche. Astfel, ceea ce noi am denumit ca şi Incinta I, are o suprafaţă de 14 ha şi un perimetru de 1524 m. Incinta II acoperă o suprafaţă de aproximativ 50 ha şi un perimetru de 2860 m. Incinta III, cea mai mare, are o suprafaţă de 80 ha şi un perimetru de 3630 m. Săpăturile arheologice din 2009 au arătat că aceasta din urmă prezintă un val înalt de 2,44 m şi lat de 26,82 m. Luând aceste numere

earthen vallum. The ditch bottom area has an oval shape, slowly elevated towards the interior of the earthwork. The ditch is dug directly into the yellow clay, down to the sandy yellow-reddish layer. The filling contains ceramic fragments, a complete pot, multiple human bone fragments and a whole deer antler. The different layers of earth prove that the ditch was seriously clogged up even before burning the whole structure of the wall. The research conducted on the field, as well as the study of different maps, led us to take under consideration the possibility of a water flow being diverted into the defensive ditch. Today, we are able to see the third enclosure obstructing an old river bed, in the vicinity of our excavation, a river bed which has been identified behind the earthen vallum.

The estimate size of the three enclosures

We were able to estimate the size of the three enclosures based on the measurements performed on the field, on the information supplied by the aerial photographs and the data provided by the Google Earth software. So, the zone we labelled as Enclosure I, had a surface area of 14 ha and a perimeter of 1524 m. Enclosure II covered a surface of around 50 ha and a perimeter of 2860 m. Enclosure III, the biggest, had a surface area of 80 ha and a perimeter of 3630 m. The archaeological investigations conducted in 2009 revealed that the last enclosure mentioned above included a wave of 2.44 m

37

Fig. 33. Şanţul de apărare/ The defense ditch

Fig. 34. Şanţul de apărare/The defense ditch

38

ca dimensiuni medii pentru întreaga lungime de 3630 m a valului incintei III, ar rezulta un volum de pământ excavat de 237.550,1 m3. Pentru şanţul de apărare, dacă folosim aceleaşi dimesiuni medii surprinse în săpătură (2,86 m adâncime şi o lăţime de 10,20 m), obţinem un volum de pământ săpat de 105.894,36 m3. Pentru a suplini diferenţa de pământ necesară ridicării valului

Fig. 35. Fotografie aeriană a fortificaţiei (după Stefan 1999)/Aerial photography of the earthwork (after Stefan 1999)

high and 26.28 m wide. If we take into consideration these numbers as average measurements for the entire length of the earthen vallum of enclosure III, the displaced quantity of earth rises up to around 237,220.1 m3. In the case of the defensive ditch, if we take into consideration the average dimensions estimated during the excavation (2.86 m deep and 10.20 m wide), we obtain a volume of

39

s-a excavat în spatele acestuia. Astfel, plecând de la un calcul mediu de 2 m adâncime şi 29 m lăţime, atât cât are şanţul în săpătura noastră, rezultă un volum de 210.540 m3. Evident că aceste calcule sunt pur orientative, dar ele demonstrează o dată în plus efortul uriaş depus pentru construirea fortificaţiei incintei a III-a de la Sântana Cetatea Veche.

Descoperirile arheologice din jurul fortificaţiei

Pe lângă fortificaţia de la Cetatea Veche, în jurul localităţii Sântana au mai fost identificate de-a lungul timpului încă 17 situri arheologice. Am văzut că tell-ul de la Holumb este menţionat în literatura de specialitate încă de la sfârşitul secolului al XIX-lea şi tratat ca fiind contemporan cu ringul avar (Márki 1882, 117-118). Numeroasele cercetări de teren efectuate aici de către Egon Dörner şi sondajul lui Sever Dumitraşcu din anul 1963 au certificat existenţa unui tell Tiszapolgár (cca. 4500 - 4300-4200 a.Chr.), precum şi a unui nivel ce poate fi atribuit perioadei mijlocii a epocii bronzului, grupului Corneşti-Crvenka (Rusu 1971, 79-80; Dumitraşcu 1975). Alte descoperiri ce aparţin epocii bronzului au fost identificate în incinta fostei ferme Trifu, situată la vest de oraş (Barbu et alii 1999, 113, pct. 3). În urma unor cercetări de suprafaţă efectuate de către Lucian Mercea şi membrii colectivului Complexului Muzeal Arad (Victor Sava, Florin Mărginean), în anul 2007 a fost descoperit la nord-vest de oraş un tell de mari dimensiuni. Ceramica găsită la

105,894.36 m3 of excavated earth. In order to make up for the lack of earth necessary to raise the earthen vallum, diggings were also carried out behind it. So, starting with an average calculation of 2 m deep and 29 m wide ditch, the measurements of the ditch during our excavations, it results a volume of 210,540 m3. Obviously, these figures are purely theoretical, but they prove once more the tremendous effort involved in constructing the third enclosure from Sântana Cetatea Veche.

Archaeological discoveries around the earthwork

Over the time, other 17 archaeological sites have been discovered in the neighbourhood of Sântana, in addition to the earthwork from Cetatea Veche. We have noted that the Holumb tell is mentioned in the specialized literature and is regarded as contemporary with the Avar ring (Márki 1882, 117-118). Multiple field research in this area conducted by Egon Dörner, as well as Sever Dumitraşcu’s test excavation in 1963 proved the existence of a Tiszapolgár tell (around 4500 - 4300-4200 BC), as well as a layer that might be assigned to the middle Bronze Age, to the Corneşti-Crvenka group (Rusu 1971, 79-80; Dumitraşcu 1975). Other archaeological discoveries from the Bronze Age were found inside the former Trifu farm, located on the West side of the town (Barbu et alii 1999, 113, pct. 3). Following several surface research made by Lucian Mercea and members of the Museum Arad (Victor Sava, Florin Mărginean), in 2007 a large scale tell

40

suprafaţă aparţine grupului Corneşti-Crvenka al culturii Vatina şi este caracteristică perioadei mijlocii a epocii bronzului (cca. 2100 – 1600-1500 a.Chr.). Confirmarea faptului că zona înconjurătoare actualei localităţi Sântana a reprezentat de-a lungul epocilor istorice un mediu propice locuirilor umane a venit în anul 2009, tot ca urmare

Fig. 36. Descoperiri arheologice în zona Sântana (sursa Google Earth)/Archaeological discoveries from Sântana area (source Google Earth)

was discovered in the North-West part of the town. The ceramic discovered at the surface belonged to the Corneşti-Crvenka group, Vatina culture and was characteristic of the middle Bronze Age period (around 2100 – 1600-1500 BC). The field research investigations carried out in 2009 also confirmed the fact that the area surrounding

41

a unor cercetări de teren. Perieghezele s-au concentrat înspre latura sud-estică a oraşului, urmând tronsonul viitoarei magistrale de gaz Sântana-Pâncota. Pornind din nord-estul fortificaţiei, pe un tronson de circa 7 km au fost identificate 11 situri arheologice. În primii 2,5 km au fost descoperite 5 situri preistorice, restul aparţin secolelor II-IV d.Chr. şi secolelor XI-XIII d.Chr. Din punct de vedere cronologic cele cinci situri preistorice pot fi atribuite epocii târzii a bronzului, fiind contemporane cu diversele faze ale fortificaţiei de la Cetatea Veche. Descoperirile din secolele II-IV d.Chr. se află la mică distanţă de necropola şi aşezarea săpată de către Egon Dörner în 1951 şi 1954 (Dörner 1960a), respectiv Mircea Barbu, Egon Dörner în 1979 (Barbu, Dörner 1980).

Elemente de cronologie relativă şi absolută ale celei de-a treia incinte

Observaţiile stratigrafice şi materialele arheologice descoperite în campania arheologică a anului 2009 permit fixarea în timp a momentului construirii, funcţionării şi mai apoi a distrugerii fortificaţiei (incintei) a III-a de la Sântana Cetatea Veche. În diversele lentile de pământ care constituie miezul valului, într-o evidentă poziţie secundară, au fost găsite fragmente ceramice care pot fi atribuite unei etape târzii a epocii bronzului. Ele au ajuns în această situaţie odată cu pământul adus pentru înălţarea viitorului val al fortificaţiei a III-a. În faţa fortificaţiei (incintei) a II-a au fost identificate urme slabe

Sântana represented a suitable environment for human dwellings throughout various historical ages. The field surveys focused on the South-East side of the town, following the lining of the future gas pipeline Sântana-Pâncota. Starting on the North-East end of the earthwork, 11 archaeological sites were discovered over a 7 km road sector. Five prehistoric sites were discovered along the first 2.5 km sector; the rest of the sites dated from 2nd-4th century AD and 10th-13th century AC. Chronologically, the five prehistoric sites might be assigned to the late Bronze Age, contemporary with the different stages of the fortification from Cetatea Veche. The archaeological findings from 2nd-4th century AD were close to the necropolis and the settlement uncovered by Egon Dörner in 1951 and 1954 (Dörner 1960a), respectively Mircea Barbu, Egon Dörner in 1979 (Barbu, Dörner 1980).

Issues on relative and absolute chronology of the third enclosure

The stratigraphic observations and the archaeological artefacts discovered during the archaeological research conducted in 2009 allowed us to pinpoint in time the building, the use and then the destruction of the third fortification (enclosure) from Sântana Cetatea Veche. Ceramic fragments that belong to the late Bronze Age were found in different layers of earth within the earthen vallum core, in a secondary position. The fragments ended up in that position with the earth

42

de locuire, iar în zona investigată de noi a funcţionat probabil şi o necropolă. Astfel în solul virgin din punct de vedere arheologic, în spatele valului III, imediat sub ultimele lentile de pământ adus, au fost identificate două

morminte. Unul de incineraţie şi al doilea de inhumaţie. Mormântul de incineraţie a avut ca inventar recipiente caracteristice bronzului târziu. Mormântul al doilea, care era deranjat, nu a fost cercetat integral aşa încât nu ne putem pronunţa încă cu privire la datarea sa. Cert este că defunctul incinerat a ajuns în pământ înainte de ridicarea

Fig. 37. Reconstituire a vaselor descoperite între lentilele valului/ Reconstruction of the vessels found betwenn the vallum loops

Fig. 38. Vas descoperit în şanţul de apărare/Vessel discovered in the defence ditch

brought in for the elevation of the future earthen vallum of the third enclosure. Several weak dwelling traces were found in front of the second enclosure, and a necropolis might have been operational in the area investigated by our team. Thus, within the sterile stratum, from an archaeological perspective, behind the third earthen vallum, immediately under the last layers of earth brought in, two graves could be identified: an incineration grave and an inhumation grave. The inventory of the incineration grave included vessels characteristic of the late Bronze Age. The second grave, which had

43

valului al III-lea, moment ce poate fi plasat cândva în bronzul târziu. Importante pentru stabilirea cronologiei relative a fortificaţiei a III-a de la Sântana Cetatea Veche sunt şi piesele de bronz (un vârf de săgeată, un ac de cusut şi un saltaleon) şi fragmentele ceramice găsite pe fundul unui curs de apă care nu mai funcţiona în momentul în care a fost ridicată fortificaţia. Este posibil ca cei doi saltaleoni şi brăţara de bronz (cu secţiunea rectangulară şi capetele ascuţite), descoperite în diversele lentile de pământ care constituie structura valului, să fi fost pierdute de cei care au participat la construirea fortificaţiei şi să nu fi provenit din aşezarea de bronz târziu de unde a fost adus pământul. Poate cele mai certe elemente de datare relativă a fortificaţiei a III-a sunt descoperirile din şanţul de apărare. În acest sens este de menţionat un vas ceramic aproape întreg care a ajuns în şanţ încă pe când

Fig. 39. Ac de cusut confecţionat din bronz/Bronze needle

Fig. 40. Vârf de săgeată confecţionat din bronz/Bronze arrowhead

been disturbed, was not fully investigated, so, for the moment, we could not determine its dating. What we do know is that the incinerated person was buried before the construction of the third earthen vallum, a moment which could be placed sometime in the late bronze period. Other important elements for establishing the relative chronology of the third enclosure from Sântana Cetatea Veche are the bronze artefacts (an arrow head, a sewing needle and a saltaleon – decorative tubules) and the ceramic fragments found on the bottom of a river bed,

no longer in use after the construction of the earthwork. The two saltaleons and the bronze bracelets (rectangular shaped, with pointed ends) discovered in different earth layers are likely to have been lost by the workers building the earthwork and may not originate from the

44

acesta funcţiona.Deocamdată nu deţinem date 14C care să permită

datarea absolută a fortificaţiei a III-a de la Sântana Cetatea Veche. Trebuie să apelăm, în acest moment, la analogii din obiective contemporane. Ne referim în primul rând la marea cetate de pământ de la Corneşti Iarcuri, judeţul Timiş, care a fost plasată între 1400 şi 1250 a.Chr.

Fig. 41. Brăţară de bronz descoperită în timpul cercetărilor de teren (2009)/Bronze bracelet found during field surveys (2009)

Fig. 42. Topor de bronz descoperit în timpul cercetărilor de teren (2009)/Bronze ax found during field surveys (2009)

late bronze settlement providing the earth. But the most reliable elements for the relative chronology of the third enclosure are discovered in the defensive ditch. One of them is a ceramic vessel that ended up in the ditch while the ditch was still operational.

For the time being we have no 14C data to allow us the absolute dating of the third enclosure from Sântana Cetatea Veche. We must use analogies with other contemporary sites. Our main reference site is the great earthwork from Corneşti Iarcuri, Timiş County, which is dated between 1400 and 1250 BC.

45

46

Fig. 44. Săparea valului şi înregistrarea datelor/Excavating the earthen vallum and recording the datas

Fig. 46. Săparea valului şi a zidului de lut/Excavating the earthen vallum and the wall

Fig. 45. Apus de soare văzut de pe fortificaţie/ Sunset seen from the earthwork

Fig. 43. Fotografie a secţiunii S1/Photography of trench S1

47

Fig. 47. Săparea şi curăţarea zidului de lut/Excavating and cleaning the wall

Fig. 49. Poziţionarea scării pentru fotografierea valului/Arranging the ladder in order to take pictures of the earthen vallum

Fig. 48. Pregătirea pentru fotografierea zidului de lut/Getting the wall ready for photography

48

Fig. 50. Conturarea şi numerotarea lentilelor de pământ de pe profilul nordic al valului/Outlining and labelling the earthen loops on the northern profile of the vallum

Fig. 52. Conturarea lentilelor de pământ de pe profilul sudic al şanţului de apărare/Outlining the earthen loops on the southern profile of the defence ditch

Fig. 51. Conturarea şi numerotarea lentilelor de pământ de pe profilul sudic al valului/ Outlining and labelling the earthen loops on the southern profile of the vallum

49

Fig. 53. Pregătirea pentru fotografierea şanţului de apărare/Getting ready in order to take pictures of the defence ditch

Fig. 54. O parte a echipei de cercetare, campania anului 2009/Part of the research team, campaign 2009

50

51

Prieteni sau duşmani

Friends or enemies

52

Cercetările arheologice moderne de pe movila de la Hisarlık (Turcia) au demonstrat că cele povestite de Homer despre Troia au un mare sâmbure de adevăr (Troia...; Troia. Archäologie eines Siedlungshügels...). O cetate înfloritoare, puternică şi mândră nu putea să nu stârnească duşmănii, dar se putea baza, de voie sau de nevoie, şi pe aliaţi fideli. Foarte probabil şi Cetatea Veche de la Sântana a făcut parte dintr-un sistem politic asemănător. Aşa cum vom vedea, ea nu este o descoperire izolată în câmpia de la Mureşul de jos; la distanţe mai mari sau mai mici, la nord sau la sud, au fost ridicate şi alte cetăţi. Cine să fi fost cei care au atacat-o şi distrus-o?

Orosháza Nagytatársánc, comitat Békés, Ungaria

Dintre descoperirile apropiate de Sântana Cetatea Veche, de pe teritoriul actual al Ungariei, am ales să consemnăm câteva informaţii cu privire la fortificaţia de pământ de la Orosháza Nagytatársánc.

The modern archaeological investigations at Hisarlık mound (Turkey) proved that Homer’s stories about Troy were close to the truth (Troy ...; Troy. Archäologie eines Siedlungshügels...). It was understandable that a flourishing, strong and proud fortress had enemies, but in times of distress it could count on its faithful allies. Most likely, Cetatea Veche from Sântana was part of a similar political system. As we are about to see, the earthwork was not isolated in the Lower Mureş Plain. Other fortresses were built in the neighbouring area, at different distances towards North or South. So who attacked and destroyed it?

Orosháza Nagytatársánc, Békés County, Hungary

As analogies to Sântana Cetatea Veche were discovered on the present day territory of Hungary, we have decided to insert here some information regarding the earthwork from Orosháza Nagytatársánc.

53

Localizarea fortificaţiei

Micul oraş Orosháza se găseşte la extremitatea estică a comitatului Békés, între alte două oraşe tipice pentru câmpia de sud a Alföldu-lui: Hódmezővásárhely şi Békéscsaba. Distanţa pâna la graniţa de stat cu România este de aproape 40 de km, iar faţă de Sântana de circa 50 de km. Fortificaţia, al cărui toponim este Nagytatársánc, este amplasată la circa 10 km sud-est de Orosháza, pe partea stângă a drumului secundar ce duce spre Kaszaper.

Fig. 55. Imagine din satelit a fortificaţiei (sursa Google Earth)/Satellite image of the earthwork (source Google Earth)