No i Perspective

-

Upload

otilia-munteanu -

Category

Documents

-

view

234 -

download

0

Transcript of No i Perspective

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

1/337

NOI PERSPECTIVE N ISTORIOGRAFIA EVREILOR DIN ROMNIA

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

2/337

Redactor:

Coperta:

V. AUERBACH

Done STANTehnoredactarecomputerizat: Dan-Constantin PINTILIETraducere rezumate

n limba englez: George WEINERCorectur texte

n limba englez: Chris DAVIS

Editura Hasefer a F.C.E.R.str. Vasile Adamache, nr. 11Bucureti 030783 Romnia

Tel/fax: 004.021.3086208e-mail: [email protected]

Descriere C.I.P. a Bibliotecii Naionale:

mailto:[email protected]:[email protected]://www.hasefer.ro/http://www.hasefer.ro/mailto:[email protected]:[email protected] -

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

3/337

FEDERAIA COMUNITILOR EVREIETI DIN ROMNIA CULTUL MOZAIC

Centrul pentru Studiul Istoriei Evreilor din Romnia

NOI PERSPECTIVEN ISTORIOGRAFIA EVREILOR

DIN ROMNIA

Ediie ngrijit de:

Liviu Rotman (coordonator)Camelia Crciun

Ana-Gabriela Vasiliu

Bucureti, 2010

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

4/337

Carte editat cu sprijinul Departamentului pentru Relaii Interetnice

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

5/337

SUMAR

Cuvnt nainte 11

SECIUNEA I.PROBLEME CONCEPTUALE I METODOLOGICE

Liviu Rotman, Prioriti n istoriografia evreilor din Romnia 15

Shlomo Leibovici Lai, Surse arhivistice pentru istoria evreilor din

Romnia 23

Ladislau Gymnt, The Perspectives of the Jewish Genealogical

Research in the Askenazi World from Central and Eastern Europe 28

Lya Benjamin, Integrare i respingere cazul dublei identiti la

evreii din Romnia 42

Lucian-Zeev Hercovici, Problema utilizrii izvoarelor ebraice

pentru cercetarea istoriei evreilor din Romnia n epoca medieval i

modern 48Claudia Ursuiu, Pe drumul ctre modernitate: cteva consideraii

privind emanciparea femeii evreice din Romnia 74

Raphael Vago, Israeli Perceptions on the Fate of Romanian Jewry.

1948-1952 86

Ditza Goshen, Un centru universitar ierusalimitean de studiere a

istoriei evreilor din Romnia: istoric, profil, perspective 96

Michael Shafir, Denazificarea: mit i realitate n perspectivistoric 101

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

6/337

SECIUNEA A II-A. ISTORIA EVREILOR

Daniela Rdescu, Bresle evreieti din ara Romneasc n

perioada regulamentar 124

Mriuca Stanciu, Manuale ale colii evreieti moderne 135

Dafna Cellier, Activitatea economic minoritar. Studiul de caz:

evreii din vechiul regat: 1859-1914 149

Hildrun Glass, Cteva note despre activitatea lui Avram L. Zissu162

Hary Kuller, Intelighenia evreiasc n anii comunismului local.

Consideraii preliminare i studiu de caz 168

Natalia Lazr, Emigrarea evreilor din Romnia 193

Anca Ciuciu, Devastarea Templului Coral din 20 septembrie 1963 n

lumina notelor informative ale Securitii 211

SECIUNEA A III-A. ANTISEMITISM I HOLOCAUST

Ana-Maria Brbulescu, Antisemitism n Romnia interbelic. n

cutarea unui Romn Imaginar 225

Alexandru Florian, Holocaustul ca subiect legislativn Romnia 240

William Totok, Maetrii morii. Despre ncercarea de renviere a

cultului luiMoa ial lui Marin 255

Cosmina Guu, Emergena memoriei colective a Holocaustului n

Romnia (1944 - 1947) 270

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

7/337

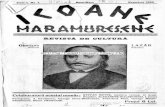

SECIUNEA A IV-A. CULTURA EVREIASC

Dumitru Hncu, araga: o familie evreiasc n societatea

romneasc 299

Camelia Crciun, Between Jewish Intellectual and Jewish

Literature: Conceptual Debates in Intellectual History 308

icu Goldstein, Un gnditor uitat sau ignorat

Alexandru Tilman-Timon 316

Ovidiu Pecican, Jean Ancel i cealalt istorie a Romniei 327

Lista contributorilor 337

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

8/337

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Foreword 11

SECTION I. CONCEPTUAL AND METHODOLOGICAL ISSUES

Liviu Rotman, Priorities in the Historiography of the Romanian

Jews 15

Shlomo Leibovici Lai, Archival Sources for the Study of the

History of Romanian Jews 23

Ladislau Gymnt, The Perspectives of Jewish Genealogical

Research in the Askenazi World of Central and Eastern Europe 28

Lya Benjamin, Integration and Rejection The Case of the

Double Identity of the Romanian Jews 42

Lucian-Zeev Hercovici, The Use of Hebrew Sources for

Researching the History of Romanian Jewry in Medieval and Modern

Times 48

Claudia Ursuiu, The Path to Modernity: Some Considerations

about the Emancipation of Jewish Women in Romania 74

Raphael Vago, Israeli Perceptions on the Fate of Romanian

Jewry. 1948-1952 86

Ditza Goshen,A Jerusalem-based University Center for Studying

the History of Romanian Jews: Historical Overview, Features,

Perspectives 96

Michael Shafir, Denazification: Myth and Reality from a Historical

Perspective 101

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

9/337

SECTION II. JEWISH HISTORY

Daniela Rdescu, Jewish Guilds in Wallachia during the Period of

the Organic Statute 124

Mriuca Stanciu, Textbooks of Modern Jewish Schools 135

Dafna Cellier, The Economic Activity of National Minorities. Case

Study: The Jews of Wallachia: 1859-1914 149

Hildrun Glass, Some Notes on Avram L. Zissus Activity 162

Hary Kuller, Jewish Intelligentsia during the Communist Regime

in Romania. Preliminary Considerations and Case Study 168

Natalia Lazr, The Emigration of the Jews from Romania 193

Anca Ciuciu, The Devastation of the Coral Temple on September 20,

1963, as presented in the information notes of the State Security 211

SECTION III. Antisemitism and Holocaust

Ana-Maria Brbulescu,Anti-Semitism in Romania between the Two

World Wars. Looking for an Imaginary Romanian Typology 225

Alexandru Florian, The Holocaust as a Legislative Matter

in Romania 240

William Totok, Masters of Death. About the Attempt to Revive the

Cult for Moa and Marin 255

Cosmina Guu, Emergence of the Collective Memory of the

Holocaust in Romania (1944 - 1947) 270

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

10/337

SECTION IV. JEWISH CULTURE

Dumitru Hncu, araga: A Jewish Family in the Romanian

Society 299

Camelia Crciun, Between Jewish Intellectual and Jewish

Literature: Conceptual Debates in Intellectual History 308

icu Goldstein,A forgotten or ignored thinker AlexandruTilman-

Timon 316

Ovidiu Pecican, Jean Ancel and Romanias other history 327

Contributors List 337

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

11/337

Cuvnt nainte

Volumul de fa se dorete a fi o mrturie a principalelor direcii decercetare n istoria evreilor din Romnia.

Volumul are ca nucleu contribuiile tiinifice prezentate lasesiunea jubiliar a CSIER din noiembrie 2007, la care s-au adugat

i alte materiale solicitate ulterior diverilor cercettori i considerateca semnificative.Reprezentativitatea volumului este asigurat de prezena unor

multiple preocupri, de istorie social, cultural, politic, istorie aantisemitismului etc., de zonele academice diferite din care vindiverii contributori, ct i de vrsta diferit a autorilor. Acest ultimaspect ni se pare de o importan deosebit, volumul prezentndu-seca una din formele multiple de predare a tafetei i implicit deasigurare a viitorului acestei discipline tiinifice.

n acelai timp, suntem contieni c o serie de teme importantelipsesc i aceste absene sunt i ele importante, cci sunt un semnal

ajuttor pentru direciile spre care trebuie s ne ndreptm n viitorefortul de cercetare.Departe de a prezenta o poziie monolit, de a ncerca s dea o

linie, volumul i implicit, CSIER, ca instituie editoare mpreun cuEditura Haseferse dorete un centru sau unul dintre centrele de dezbateri pe temele ce compun complexa disciplin a istorieievreilor.

Dorim s cultivm metode academice de cercetare care cuprindfolosirea critic i onest a izvoarelor, preluarea, de asemenea critica literaturii istorice trecute i n special, o tratare obiectiv, cumpnitdin care s lipseasc tonul hagiografic.

Acest volum se vrea, de fapt, doar un prim pas al unei dezbateriacademice.

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

12/337

12 Cuvnt nainte

Mulumirile mele se ndreapt spre toi colaboratorii volumului,ncepnd cu autorii contribuiilor, ctre colegele mele care m-ausecondat n editarea volumului, Camelia Crciun i Ana-GabrielaVasiliu, ctre Editura Hasefer, care a ncurajat aceast apariie i nprimul rnd directorul acesteia, tefan Iure i redactorul de carte, V. Auerbach, ctre ing. Dan Pintilie, care a asigurat tehnoredactareacomputerizat a volumului.

Liviu Rotman

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

13/337

SECIUNEA I

PROBLEME CONCEPTUALE I METODOLOGICE

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

14/337

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

15/337

PRIORITI N ISTORIOGRAFIA EVREILOR DIN ROMNIA

Liviu Rotman

Cred c, periodic, o disciplin tiinific trebuie s aib un momentde bilan i n special, s-i revizuiasc drumul conceptual imetodologic. De aici i ncercarea noastr de a realiza un inventarde probleme al cercetrii n acest domeniu.

Cercetarea istoric n general i istoria evreilor nu face excepie este influenat de micarea ideilor n general, de tendinele

culturale dominante n epoc, de situaiile politice noi, de apariiaunor instrumente noi de cercetare .a.m.d. Cu tot respectul pe care lpurtm naintailor, nnoirea abordrii este o obligaie a cercettoruluiautentic. n acest caz, nnoirea nunseamn ignorarea naintailor,ci, dimpotriv, preluarea continu a acestora cu spirit critic, fridealizri i folosindu-se de ceea ce ei au pus n circulaie pentru agsi noi unghiuri de abordare a trecutului istoric. Acest lucru se poaterealiza prin intensificarea efortului de a gsi noi surse, dar i printr-olectur nou a informaiilor existente.

Istoria poporului evreu a cunoscut de-a lungul timpului diverseinterpretri legate de strategiile social-politice ale societii evreieti

din acel moment. n perioada colii Wissenschaft des Judentums,istoria evreilorera considerat o istorie a faptului religios, aa cumo definete Immanuel Wolf, drept care accentul cade pe aceastncrctur religioas; n acest mod, istoria evreilor este egal cuistoria iudaismului.

Astfel, istoria evreilor din a doua jumtate a secolului 19, expresiea eecului liniei de integrare a evreilor in mediile social-culturalenconjurtoare i a unor noi cutari ce vor anuna sionismul, vacunoate o schimbare de orientare. Nu ntmpltor, unul din pionieriiistoriografiei evreieti, Heinrich Graetz, i prefaeaz monumentalasa lucrare de 6 volume, aprut ntre 1891 i 1898 (sic!!!), cu un

studiu intitulat Reconstruciunea naiunii evreieti. Aadar, accentulse mut dinspre evrei ca religie spre evrei ca popor sau naiune1.Simon Dubnow are meritul de a aduce, primul n istoria evreiasc, oconcepie sociologic ce aeaz n centrul preocuprilor sale

1Heinrich Graetz, History of the Jews, Philadelphia, 6 vols, 1891-1898.

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

16/337

16 Liviu Rotman

instituia social, concepie ce este deosebit de actual. O formulasemntoare, dar mai laicizat, o d Simon Dubnow n lucrarea safundamental de istorie a poporului evreu.1

Apariia Statului Israel va da o nou soluie. Tnra viaacademic a noului stat a adoptat conceptul toldot am israel (istoriapoporului evreu), formul care presupune o orientare spre tot ce ansemnat trecut evreiesc. Avem de-a face cu o formul integratoare,nsuit i de istoriografia american.

Specificitatea istoriei evreieti rspndirea comunitii pe o maresuprafa a lumii creeaz, de asemenea, dificulti attconceptuale, ct i metodologice. Conceptual, cercettorul este pus

n faa dilemei: ce este istoria evreilor o sum de istorii ale unorminoriti (istoria evreilor din Polonia, Romnia sau Yemen), sausinteza (de altfel, nu uor de realizat i mai ales de atins)? Dupcum spune istoricul Shmuel Trigano, problema esenial a istorieievreieti, ca noiune i disciplin academic, ine de experiena unica unui grup uman a crui memorie istoric are ambiia s se coboaredin Antichitate, [i care este] risipit pe toat suprafaa lumii moderne,n inima naiunilor i imperiilor cele mai diverse, n toate ariileculturale2

Este evident c ncercarea de a realiza o istorie integral a unuiastfel de popor este un demers intelectual deosebit de dificil, dar i

un ideal atractiv. ntr-adevr, a cerceta n profunzime diverselefragmente, dar a menine n permanen legatura cu ntregul, estedificil. Cci avem, de fapt, de-a face cu o istorie virtual, care poate fineleas bine abia acum, n epoca internetului.

Dar, firete, dificultile sunt i de ordin metodologic: cuprindereaunor surse documentare, dar i materiale extrem de diverse,folosirea unor limbi diferite (obstacol foarte serios), necesitatea de acunoate bine istoria i civilizaia popoarelor n mijlocul crora au tritevreii.

O istorie n Diaspora, inclusiv a evreilor, are dou planuri: celintern i cel extern.

1. Planul intern, mai greu de descifrat, cuprinde probleme alesocietii, culturii, nvmntului i mentalitilor.

1Simon Dubnow, Jewish History. An Essay in the Philosophy of History,

Philadelphia, 1903.2

Shmuel Trigano ed., La socit juive travers lhistoire, vol. 1, p.13.

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

17/337

Prioriti n istoriografia evreilor din Romnia 17

2. Planul extern, care cuprinde complexul relaiilor dintre evrei ipopoarele n mijlocul crora triesc.

Considerm c, n prezent, prioritar este explorarea planuluiintern, a fenomenelor luntrice societii evreieti. Dintre acestea, oprim urgen este istoria social, i, n cadrul acesteia, cercetareainstituiei funadamentale a Diasporei evreieti: Comunitatea1.

Aici se impune o optic nou asupra conceptului de istorie aComunitii; se vizeaz trecerea de la perspectiva prezentat pn nprezent ca istorie a evreilor dintr-o anume aezare spre istoriainstituiei comunitare. Aici trebuie depit stadiul meritoriu almonografiilor aprute (cum sunt cele ale regretatului Itzic Kara i

care au merite deosebite, n special n planul documentrii), nprezent fiind necesar un nou tip de explorare care s ne dezvluiecum funcionau aceste organisme, cum funciona n general auto -guvernarea comunitar evreiasc. Firete, n acest scop estenecesar o cercetare amnunit a fondurilor de arhive.

O serie de subiecte de istorie comunitar n general, precum i deistorie social n general, nu sunt nc foarte clare: sistemul dealegere a conducerii comunitare, raportul dintre conducerea laic icea religioas, funcionarea justiiei comunitare etc. n acest sens,trebuie s semnalez dou doctorate unul terminat, desprecomunitatea din Alba Iulia (Ana Maria Caloianu) i unul n curs,

despre comunitile din nord-vestul Transilvaniei (Gido Attila). Un altdoctorat, cu o bogat documentare, nchinat unei comuniti,aparine Mariei Gioal din cadrul Facultii de Istorie a UniversitiiBucureti2.

n istoria culturii s-au fcut pai mari n ultima vreme, dar accentula czut tot pe aspectul exterior. Cunoatem din ce n ce mai binecreatorii evrei prezeni n cultura romn sau n cea european(avangarditii), dar cunoatem mai puin sau deloc pe aceia care aucreat n cultura evreiasc propriu-zis, n ebraic sau idi. Aici asublinia doctoratul Mriuci Stanciu, care prezint un Gasternecunoscut3.

1Vezi Liviu Rotman, A scholary Urgency, the Social History of Romanian Jewry

n Studia Hebraica, 2/2002.2Maria Gioal,Istoricul comunitii evreieti din Ploieti, Bucureti, Editura Hasefer,

2008.3 Mriuca Stanciu, Necunoscutul Gaster, Bucureti, Editura Universitii

Bucureti, 2006.

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

18/337

18 Liviu Rotman

O tem prioritar de cercetare ar trebui s fie cea a producieieditoriale evreieti (doctoratul Mariei Radosav, pentru nord-vestul Transilvaniei1), dar ar fi necesar i explorarea ediiilor dinMoldova. Moshe Idel ne atrgea atenia asupra sutelor de titlurihasidice aprute n varii tipografii din Moldova. Influena hasidismuluieste notabil n civilizaia evreilor, dar, mai mult dect att, i nliteratura romneasc. O provocare n domeniu este aceea de acompara tipriturile din diverse orae din Moldova cu titlurile dinevidenele clasice ale istoriei crii romneti (BibliografiaRomneasc Veche (BRV) i Bibliografia Modern a Romniei).

Pregtirea viitorului cercettor existena liniilor de masterat de la

Cluj, Bucureti, Iai, Arad, Craiova etc. este poate fenomenul celmai important n dinamica cercetrii istoriei evreilor din Romnia. naceast ordine de idei, va trebui corectat o optic tributarizvoarelor: necesitatea de a recunoate c a existat o pluralitate dedireciide via i organizare comunitar. De exemplu, la mijloculsecolului 19, n Bucureti erau de fapt mai multe comuniti evreieti:sefard, akenaz (leeasc sau polonez) ultra-religioas(haridim-i) i cea a Templului Coral, ultima fiind exponenta unei eliteevreieti moderne, cu tendine reformiste. Au existat n paralel, cuputernice conflicte, comuniti raia(pmnteni)i sudii, de care s-aocupat Mihai Rzvan Ungureanu.

Este necesar o aprofundare a tuturor acestor curente; ne-amobinuit s vedem de multe ori istoria evreilor prin ochelarii unoractori ai vremii care, prin fora lucrurilor, nu sunt obiectivi. n primulrnd a maskilim-ilor (mai culi, mai apropiai de spiritul nostru,posesori ai unei scriituri convingtoare), dar nu putem ignora c ei nusunt singura direcie din mentalul colectiv evreiesc al epocii, pentruc existau i alte direcii de gndire.

n acest sens, un bun exemplu este imaginea colii evreieti aepocii, heder-ul. Aceast imagine se contureaz n primul rnd dinscrierile intelectualilor iluminiti precum Iuliu Barasch saureprezentantul lui Alliance Israelite Universelle, Is. Astruc. Imaginea

transmis de ei este mai mult dect cenuie. Este firesc, ei veneaucu o ofert cultural nou, modernizatoare i negau formatradiional. Nu discutm aici cine avea dreptate. Nu este locul.

1Maria Radosav, Livada cu rodii. Carte i comunitate evreiasc n nordul

Transilvaniei (secolele XVIII XX), Cluj-Napoca, Editura Argonaut, 2007.

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

19/337

Prioriti n istoriografia evreilor din Romnia 19

Pledez doar pentru o prezentare echilibrat n cadrul istoriei evreilor.Trebuie s inem seama c, privit din perspectiv istoric, heder-ul aavut un rol uria n dinamica spiritual evreiasc. Premiile obinute ncolile romneti, diplomele din marile universiti europene au fostfacilitate absolvenilor de heder pentru c acetia beneficiau deobinuina efortului de instrucie, ba chiar de sacralizarea acestuiefort.

Habitatul evreiesc este i el o mrturie a mentalului colectiv, acrui cercetare se impune. n aceast direcie se afl n derularedoctoratul colegei mele, Anca Ciuciu, despre cartierele evreieti dinBucuretiul secolului 19, subiect pasionant nu numai pentru istoria

Bucuretilor. S nu uitm c micrile demografice ale populaieievreieti au exportat tetl-ul n marile metropole, inclusiv la Bucureti.Ajungem astfel la problema patrimoniului cultural evreiesc

(sinagogi, cimitire, dar i alte izvoare/materiale de istorie, caechipamente industriale, obiecte tridimensionale etc.) ce ateapt orepertoriere i o cercetare autentic.

Istoria de gen n cadrul istoriei evreieti este nc la nceputuri.Remarc lucrarea n derulare a Claudiei Ursuiu de la UniversitateaBabe-Bolyai din Cluj. n acest sens, raporturile familiale, statutulfemeilor, dreptul copiilor i problema mariajului sunt domenii ncprea putin cercetate.

Problema imaginarului evreiescExplorarea imaginarului evreiesc este o alt direcie ce merit

interesul cercettorilor. Este un domeniu destul de dificil de descifrat,dar foarte important pentru limpezirea imaginii societii evreieti ndiverse momente istorice. Se impune investigarea sociologic aliteraturii evreieti i, n acest sens, semnalm lucrarea de doctorat acercettoarei clujene Simona Frcan1, ct i un recent doctorat,nc nepublicat, al Cameliei Crciun2 despre scriitorii evrei interbelici,n care se urmrete descifrarea imaginii concentrrilor evreieti prinoptica unor scriitori evrei.

1Simona Frcan, ntre dou lumi. Intelectuali evrei de expresie romn n secolul

19, Cluj-Napoca, Editura Fundaiei pentru Studii Europene, 2004.2 Camelia Crciun, Between Marginal Rebels and Mainstream Critics: Jewish

Romanian Intellectuals in the Interwar Period, Departamentul de Istorie, Budapesta,Central European University, 2009 (tez nepublicat).

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

20/337

20 Liviu Rotman

Un rol important l are studierea a ceea ce am numit societateacivil evreiasc, prin studierea formelor speciale de expresie precumzvonuri, bancuri, presa evreiasc etc. Acest gen de izvoare nu s -abucurat de atenia cercetrii pn acum i ateapt o cercetareacademic, sobr.

De asemenea, se impune i studierea unui anume tip de literatur,a presei, precum i completarea acestor surse cu istoria oral. Unstudiu asupra umorului, perceput ca o cercetare de antropologiecultural, legat de dinamica istoric (au aparut unele colecii jalnice,cu titluri penibile, ce nu merit a fi amintite) se impune. O explorareprin intermediul arhivelor (i n special a rapoartelor informative de la

Siguran i Securitate) a bancurilor, a zvonurilor, a strii de spiriteste nc un deziderat. Este, n fond, cercetarea societii civile laevrei, a spaiului altenativ pe care aceasta l ofer, n special nperioadele de regim totalitarist.

Antisemitism i HolocaustIstoria evreilor s-a ocupat n permanen de diversele forme de

antisemitism, nsoitor, din pcate, cvasipermanent al istorieisocietii evreieti. O serie de factori precum deschiderea dup 1990a arhivelor, dar i escaladarea negaionismului au stimulatcercetarea n problematica Holocaustului. n ultimii ani, cercettorii

Centrului de Istorie au fost prezeni n diversele manifestriacademice patronate de Institutul Naional pentru StudiereaHolocaustului Elie Wiesel.

n acest context, o importan deosebit a avut-o traducerea nlimba romn a operelor lui Jean Ancel ce fundamenteaz o noudisciplin academic, cea a cercetrii Holocaustului din Romnia.1De asemenea, un moment de cotitur a fost apariia Raportului finalal Comisiei Wiesel n toamna anului 2004 i care reprezint unmoment de cotitur n perceperea problematicii Holocaustului nRomnia.

Un domeniu puin abordat, sau abordat nefericit din punct de

vedere tiinific, este cercetarea strategiilor lumii evreieti n cea maigrea perioad a istoriei sale, Holocaustul, precum i cercetarea

1 Dintre cele mai importante: Contribuii la istoria Romniei. Problema evreiasc

1933-1944, 4 vols Bucureti, Editura Hasefer, 2001-2003; Preludiu la asasinat.Pogromul de la Iai, 29 iunie 1941, Bucureti, Editura Polirom, 2005.

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

21/337

Prioriti n istoriografia evreilor din Romnia 21

conducerii evreieti din Romnia n perioada Holocaustului. Dinpcate, n ultimii ani au aprut lucrri discutabile, de tip hagiografic,n care imaginea leadership-ului evreiesc n perioada Holocaustuluieste distorsionat i manipulat pentru a servi unor interese degrup.1 Pe lng titlul nefericit, lucrarea ncalc norme de baz alepublicaiilor tiinifice.

Pe lng necesitatea lrgirii ariei tematice, considerm necesari o abordare nou, un ton nou. Necesitatea consolidrii spirituluicritic, deprtarea de orice form de hagiografie, strin istoriei catiin, dar i spiritului iudaic, sunt, cred, necesiti prioritare. O

cretere a responsabilitii, o desprire de o istorie militant, oncercare de a nu gndi la reacia din afar. Respectarea adevruluiistoric relevat de diverse surse va trebui s fie axa cercettoruluiistoric n acest inceput de mileniu.

Summary

The purpose of this survey is to present an overview of theresearch on the history of Romanian Jews. At the same time, it isalso meant to present the perspectives of future development for this

area of science. The author pleads for a more balanced, generalapproach between the two parts of this field: one that relates it to thegeneral history of the Jewish people, and the other that connects it toRomanian history. Mr. Rotman resumes one of his previous thesesabout the priority of socio-historical research for a better knowledgeof Jewish society from within. He also underlines the importance ofthe rise, in quantity and quality, of those who are interested in thehistory of the Jews from Romania. The author mainly focuses on thework of younger researchers. Within this context Mr. Rotmanmentions the important role of the centers of Jewish studies especially those from the Universities of Bucharest and Cluj-Napoca

in defining the history of the Jews from Romania as a field ofacademic study, entitled to be part of the Romanian and internationalscientific branches. In general, the author underlines the importance

1Vezi Carol Iancu, Alexandru afran i oahul neterminat n Romnia, Bucureti,

Editura Hasefer, 2010.

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

22/337

22 Liviu Rotman

of the collaboration between researchers belonging to various

generations, facilitating the relay race for the research to continue.This survey pleads for a change of tone, being completely againsthagiographic works. The future evolution of this field is seen fromthe perspective of a closer collaboration between researchers fromvarious countries and areas of culture.

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

23/337

SURSE ARHIVISTICE PENTRU ISTORIA EVREILOR DIN ROMNIA

Shlomo Leibovici Lai

Cercetarea trecutului evreilor din Romnia a nregistrat n ultimiiani un oarecare avnt. Cu toate acestea, trebuie s recunoatem cne aflm abia la nceputurile ei. De aceea, cunoaterea surselor cestau la dispoziia cercettorului prezint o importan deosebit. Darnu mai puin important este i aducerea la cunotin a unor sursegreu accesibile tocmai pentru a stimula dezvluirea lor i punerea n

circuitul cercetrii.Sursele cele mai autentice se afl, bineneles, n arhive inclinaia fiecrui cercettor este de a consulta documentul originalpentru a-i da propria sa interpretare.

n alocuiunea mea, prezentat cu ocazia mplinirii a douazeci deani de la nfiinarea centrului de cercetare, aflat atunci subconducerea lui Eugen Preda i n cadrul cruia se desfoar iacest simpozion, am vorbit despre Problematica cercetrii trecutuluievreilor din Romnia, punnd accentul i pe diversitatea limbilor ncare documentele n cauz sunt scrise, nu toate stpnite de oricecercettor. Repet aceast constatare deoarece dispersarea peste

mri i ri a arhivelor la care m voi referi este legat inerent de odiversitate de limbi.Am preferat s prezint arhivele legate de tema simpozionului n

funcie de gradul lor de accesibilitate, fr ns a face abstracie decele care nc nu ofer condiii care s permit consultarea lor.

M voi strdui s indic nu numai localizarea arhivelor, dar i saduc informaii despre ce se poate gsi n ele.

n Israel, de pild, se afl o serie de arhive publice, i chiar uneleparticulare, care dein materiale importante despre evreii dinRomnia. i, dac aduc ca prim exemplu arhivele noastre, aleACMEOR (Asociaia Cultural a Evreilor Originari din Romnia), n

fruntea creia am onoarea s stau, este pentru c ele sunt singurelearhive care dein exclusiv documente legate de trecutul evreilor dinRomnia.

La ACMEOR se afl trei arhive i toate stau la dispoziiunea tuturor,de la elevi ai cursului primar care vin s fac lucrri despre rdcinilefamiliilor lor i pn la doctoranzi ce i-au ales ca tem un aspect din

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

24/337

24 Shlomo Leibovici Lai

viaa evreilor de pe aceste meleaguri. Dup cum vin i profesori careprefer s gseasc concentrate la un loc cele necesare, n loc s fieobligai s caute materialele de care au nevoie prin documente dinmulte alte puncte geografice. De altfel, aceste arhive sunt vizitate i depersoane din strintate, din Romnia i din alte ri; astfel, MuzeulHolocaustului din Washington a trimis o echip care a copiat laACMEOR microfie (peste 40 000 de file). Cele trei arhive menionatesunt arhiva propriu-zis ACMEOR, arhiva Comitetului pentru activitateacultural iudaic n rndurile evreilor din Romnia i care editeazrezultatele cercetrilor i, n cele din urm, arhiva personal.

n toate celelalte arhive pe care le vom enumera se gsesc

documente importante cu privire la evreii romni, dar nu numai cuprivire la ei. Astfel, exist Arhiva Statului Israel i Arhiva Ministerului deExterne israelian. Ambele dein rapoarte despre situaia evreilor dinRomnia n perioada existenei Statului Israel i sunt o surs serioaspentru cunoaterea vieii evreilor romni n acest timp.

La Universitatea Ebraic din Ierusalim ntlnim alte trei arhive; ArhivaIstoric Central a Poporului Evreu, care cuprinde inclusiv date idocumente din Romnia, mai ales asupra reelelor colare evreieti;arhiva Bibliotecii Naionale unde putem gsi, de pild, printre altele,fondul Zissu, astfel c cel care se intereseaz de aceast complexpersonalitate gsete aici un material relativ bogat; Arhiva Centrului

Dinur cu secia sa romneasc n care, pe lng bogata sa bibliotec,se pot gsi documente adunate cu migal de ctre TheodorLoewenstein Lavi, cercettor al trecutului evreilor din Romnia ncdinainte de venirea lui n Israel pn la arestarea sa ca sionist de ctreSecuritate i apoi, dup sosirea lui n Israel, unde i-a dedicat ntreagaactivitate strngerii de documente i cercetrii.

La Universitatea din Haifa, la Institutul de Cercetare pentru Europade Rsrit i rile din Centrul Europei nfiinat de regretatul profesorBela Vago, pot fi consultate fondul Feller (care conine o interesantcoresponden cu diverse foruri sioniste) i fondul Haomer dinTransilvania (cu interesantele rapoarte despre ncercrile comunitilor

de a atrage aceast micare din stnga sionist).La Tel Aviv, ntlnim Arhiva Hagana (inclusiv despre aportul

evreilor din Romnia la aprarea aezrilor evreieti din Palestina nperioada prestatal); Arhiva Poalei Zion pe numele lui Pinhas Lavon,aflat la Histadrut, adic la Uniunea Sindicatelor din Tel Aviv,cuprinznd documente care dovedesc legtura de lung durat

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

25/337

Surse arhivistice pentru istoria evreilor din Romnia 25

dintre micrile de pionieri sioniti din Romnia cu micareamuncitoreasc din Eretz Israel; Arhiva inter-universitar pe numelelui aul Avigur, de la Ramat-Aviv, cu un bogat material despreimigrarea ilegal din timpul Mandatului Britanic un capitolextraordinar de interesant pentru evreii din Romnia, de unde aupornit cele mai multe vase i care a dat serioase bti de cap puteriimandatare.

La Ramat-Gan, la Universitatea Bar-Ilan, cercettorul interesat detrecutul evreilor din Romnia poate consulta documente la douarhive: la Universitatea Bar Ilan se gsete o parte din Arhiva RabinMoses Rosen, organizat de Iacob Adam i de dr. Liviu Rotman, dar

i Arhiva sionismului religios, ea nsi un amalgam de arhiveprovenite din diverse ri.Dei majoritatea dosarelor i arhivelor sioniste au fost capturate

de autoritile regimului comunist i nu au fost redate nici pn astziproprietarilor lor, un material arhivistic parial se afl n Israel. Nu amrenunat i nu vom renuna la arhivele rmase n Romnia i sperms le obinem; pn atunci dorim s aflm mcar unde ar putea sconsulte documente cei interesai, cu privire la micrile sioniste detineret din Romnia.

Documente relevante se gsesc, ce-i drept, doar parial, la arhivesituate n diverse aezri din Israel precum Ghivat Haviva, centrul de

documentare pentru micarea Haomer Haair; Gu Etzion pentruBnei Akiva; kibu-ul Hulda, pentru Gordonia; Ierusalim, arhivamicrii ultra-religioase Agudat Israel; arhiva Neah, din kibuMaagan, pentru Dror Habonim i kibu-ul Mordehai Haghetaotpentru micrile de tineret din perioada Holocaustului.

Pentru relaiile cu Eretz Israel Palestina din timpul Mandatului, laSde Boker, unde este gzduit larga arhiv a lui Ben -Gurion, sepoate gsi, printre multe altele, i documentul care consemneazrefuzul autoritilor romneti de a da viza de intrare n Romniaacestui conductor care atunci prin 1946se afla n vizit la Sofiaunde a fost primit cu toate onorurile.

Exist n Israel i arhive particulare, dar accesul la ele nu este landemna fiecruia. Am amintit existena lor deoarece am gsituneori n ele ceea ce n-am gsit nicieri n alt parte. La arhivapersonal a dr-lui Shlomo Kless din kibu-ul Nir-David am vzutdocumente originale legate de aciunea trenurilor de salvare cuvagoane spital plecate n cteva curse de la Oradea Mare spre

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

26/337

26 Shlomo Leibovici Lai

lagrele din Polonia pentru a aduce de acolo supravieuitori. A fostuna din aciunile cele mai ludabile, imediat dup terminarearzboiului, iar Cile Ferate Romne care au pus aceste trenuri ladispoziie merit toat condescendena. Dar iat c acest capitol nupoate fi luminat fr arhiva particular amintit.

Materialele pariale la care avem acces, aflate n arhiveleenumerate, nu sunt destule pentru efectuarea unei cercetri integralea organizaiilor sioniste din Romnia. M fac ecoul celor din Israeladresndu-m cu aceast ocazie celor ce dein arhivele sioniste sfac tot posibilul ca arhivele sioniste s fie redate celor crora leaparin de drept i de fapt pentru a putea n sfrit realiza istoria

sionismului din Romnia.Nu avem voie s facem abstracie nici de centrele de mrturieoral de pe lng universitile din Ierusalim i Haifa. De importanai legitimitatea lor n cercetarea istoric s-au ocupat istoricul englezCar, politologul israelian profesorul Shlomo Avineri de laUniversitatea Ebraic i profesorul Ioav Gelber de la Universitateadin Haifa. n tezaurele adunate n aceste centre din pcate nudestul de exploatate se afl un material unic ce poate fi de un realajutor n cercetarea istoric.

Un capitol deosebit de important n acest domeniu este cel almanuscriselor mprtiate n diverse arhive sau departamente

speciale. Pentru exemplificare m voi rezuma la manuscrisele luiMoses Gaster care, dei expulzat n 1885, a donat manuscriselecercetrilor sale despre folclorul romnesc, precum i ntreaga luicoresponden cu Mihai Eminescu, Academiei Romne unde pot ficonsultate. Manuscrise gritoare se pot consulta i la ACMEOR,precum i la universitile din Haifa i Ierusalim i la Yad Vashem,unde se pot gsi cele ale lui Filderman i B. Brniteanu.

Cercettorul trecutului iudaismului romnesc poate gsi surse nnu puine arhive din alte ri dar, datorit timpului restrns ce-mi stla dispoziie pentru aceast comunicare, voi mai enumera numai celece mi se par mai importante.

La Paris, n arhiva Alliance Israelite Universelle, n care, dupreorganizare, cel interesat poate gsi cu mai mult uurin celecutate. La Londra, la Public Archives i, n special, n F.O. (fondulMinisterului de Externe), ca i n cel al Ministerului Coloniilor, seregsesc schimburi de adrese, inclusiv numeroasele note verbaleprezentate de reprezentanele diplomatice ale respectivelor ri.

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

27/337

Surse arhivistice pentru istoria evreilor din Romnia 27

Multe din ele ilustreaz presiunile britanice asupra Romniei cuprivire la emigrarea evreilor. La New York, n vasta arhiv a lui IWO(Judische Welt Organization) se poate gsi cam tot ce priveteliteratura idi, inclusiv cea din Romnia. De remarcat c acolo se afli arhiva personal a lui Barbu Lzreanu. Tot la New York se aflArhiva Central a Joint-ului care, cu multele dosare de activitate nRomnia n anii de dinainte de rzboi i n cei de dup, inclusiv nanii regimului comunist, constituie surs de consultat cuminuiozitate. La Washington, marea Arhiv a MuzeuluiHolocaustului, a crui secie pentru Romnia s-a mbogit cu sutelede mii de file aduse n ultimii ani din Romnia i cu zecile de mii de

micro-fie de la ACMEOR. Tot la Washington se afl The Library ofCongress, cu variatul su material, printre care se afl i dateinteresante despre Romnia care includ, de exemplu, condiionareaacordrii statutului de naiunea cea mai favorizat cu permisiunea deemigrare. La Viena, n arhivele oreneti ce adpostesc, printremulte altele, i arhivele familiei Lugger, gsim consemnate relaiiledintre regele polonez i voievodul romn cu nu puine amnuntedespre negutorii evrei din Principate i cu descrierea portului iobiceiurilor lor. Materialul aflat n aceast arhiv este de o mareimportan pentru studierea istoriei evreilor din Romnia.

n Romnia, Arhiva Preediniei Consiliului de Minitri conine

documente preioase att pentru perioada interbelic, cu indicaiipentru contribuia evreilor la dezvoltarea economic a rii, ct ipentru cea din timpul Holocaustului, i chiar pentru cea postbelic. nRomnia, documente relevante pentru istoria comunitii evreieti seafl la Arhivele Naionale, in diverse fonduri, n arhiva CSIER, nArhiva fostului Institut de Istorie a Partidului, n Arhiva SRI trecut laCNSAS i n arhiva Ministerului Cultelor. Atrag atenia c doarinvestigarea arhivistic poate da o imagine corect a istoriei secularea evreilor din Romnia.

Summary

This is an overview of relevant archival sources for the study of the history

of the Jews from Romania, Israel, France, Great Britain, the United States ofAmerica, Austria and Romania. The survey also includes a description of the

content of the archives, when they were created, their specific features, aswell as their accessibility for research.

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

28/337

THE PERSPECTIVES OF THE JEWISH GENEALOGICALRESEARCH IN THE ASKENAZI WORLD FROM

CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE

Ladislau Gymnt

Our fifteen years research experience in the field of Jewishgenealogical research has highlighted the conviction that the successof such projects depends on at least three essential elements:

The thorough and deep knowledge of the general and local

historical environment where the life of the researched familiesunfolded;

Deciphering the evolution of the systems for recording vitalevents (births, marriages, deaths);

Clarifying the location, the degree of preservation and theaccess to the archival sources, as well as to other sources availablefor the research.As far as our topic, the European Ashkenazi world, is concerned,

before anything, one should recognize that the object of our analysisis represented by the history of the Jewish families in Central andEastern Europe. It was here that this branch of the Jewish people,

also present in other parts of the continent and of the world (WesternEurope, United States, Israel etc.), was primarily concentrated,manifesting its most characteristic social, cultural, and religiousforms.

From a demographic point of view, the formation of a massiveAshkenazi populated area including present-day Germany, Austria,Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, Ukraine, Poland, theBaltic countries, Belarus and Russia is due to the massive WestEast migration between the 13th and 15th centuries, determined bythe historical vicissitudes of the Crusades and the general or localexpulsions of the Jewish population from England, France, the

different regions and provinces of the Holy Roman Empire, and evenHungary. After the flourishing of Jewish life between the 16th and18th centuries in Poland, Lithuania, Bohemia, Moravia and someparts of Germany, having an autonomous institutional system thatwas highly original and acknowledged by the authorities of the time,the indescribable atrocities of the Cossack Revolt led by Bogdan

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

29/337

The Perspectives of the Jewish Genealogical Research in the Askenazi World... 29

Hmelnicki in 16481649 mark the beginning of the decline that wasaccelerated in the 18th century by the significant geopoliticalchanges in the area. The PolishLithuanian Commonwealthdisappeared from the political map of Europe in 1795, being dividedbetween the great neighbouring powers Russia, Prussia and Austria.Moldavia, another area with a significant Jewish population, wasamputated in its turn, with the northern part (Bukovina) beingincorporated in the Austrian Empire and the region between therivers Prut and Dniester (Bessarabia) becoming part of the RussianEmpire. Considering that in Western Europe, during theEnlightenment, the ideas of tolerance that opened the way for the

civil emancipation of the Jews were gaining ground, a new andmassive EastWest migration wave brought large masses of theJewish population who had been affected by the turmoil, the warsand the territorial changes in Eastern Europe to the morewelcoming countries of the Western part of the continent and, afterthe failure of the 18481849 revolutions, to the free world across theocean.

At the same time these major directions of migration were beingshaped, regional migrations were also determining the Jewish habitatin Central and Eastern Europe. Within the Habsburg Empire, thepoor Jewish masses migrated in the 19th century from the

overpopulated shtetl regions in southern Poland (Galicia) andnorthern Moldavia (Bukovina) to the Western provinces (Austria,Hungary, the Czech and Slovak lands, and Transylvania), where theeconomic opportunities and the gradual evolution towards an equalopportunity status represented certain attractions. A significantnumber of Jews migrated from a Russia that was oppressing itsJewish population in the so-called Colonisation Area, as well as fromPoland to Moldavia, Wallachia, Hungary and Transylvania, aphenomenon whose extent was increased by pogroms, whichbecame almost daily practice after 1880. The restrictive anti-Jewishpolicy of the Romanian governments after 1866 caused at the end of

the 19th century and in the first years of the 20th century a large-scale migration of Romanian Jews towards Western Europe, theUnited States, and to the territory of the future state of Israel, due toa highly influential Zionist movement.

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

30/337

30 Ladislau Gymnt

After World War I, new Jewish population migrations weredetermined by the vicissitudes of the civil war in Russia, which,especially after the pogroms in Ukraine, caused hundreds ofthousands of Jews to take refuge in Romania, Hungary, Poland andWestern Europe. The Holocaust manifested its destructive effects inthis region, affecting the Jewish populations in Poland, the BalticStates, Ukraine, Byelorussia, Bessarabia, and Bukovina, as well asin Germany, Austria, German-occupied Czechoslovakia, andHungary, including Hungarian-ruled northern Transylvania. Despitethe outward anti-Semitic policies and the multitude of restrictive andproperty-depriving measures, a significant part of the Jewish

population in the historic lands of the Romanian Old Kingdom(Moldavia and Wallachia), in Romanian-ruled southern Transylvania,and in the Hungarian capital, Budapest, survived as a result of thefact that the Final Solution was not applied by the Romanian andHungarian governments in these regions.

After World War II, in the context of the establishment of the newcommunist dictatorship, with its frequent anti-Semitic and anti-Zionistimpulses, a large part of the Jews in Romania and Poland headed forthe State of Israel, unlike the Hungarian Jews of Hungary, whichremained primarily in Hungary. Eventually, after 1990, the fall ofcommunism and the division of the Soviet Union opened the

possibility of a massive immigration to Israel for the Jews of Russia,Belarus and Ukraine1.

As the significance of these great population migrations is evidentthrough their effects on the destinies of the individual families, whichwe intend to retrace through genealogical research, we consider itsimilarly important to know the institutional structures that throughoutthe centuries governed Jewish life in the areas subject to ourinvestigation. The general framework of the religious community andof the rabbinical institution is increased, diversified and differentiatedin the relatively favourable circumstances in the 16th18th centuriesin Poland, Lithuania, Bohemia, Moravia, Germany, Moldavia,

Wallachia, Transylvania, and Hungary. The institution of the Chief

1For the general frame of these migrations, see: H.H. Ben-Sasson,A History of the

Jewish People, Cambridge, Massachusets, Harvard University Press, 1994; CecilRoth, Histoire du peuple juif, Paris, 1980. A synthesis of the essential information in:Sallyann Amdur Sack, Gary Mokotoff, Avotaynu Guide of Jewish Genealogy,Bergenfield, NJ, 2004, pp. 73-76.

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

31/337

The Perspectives of the Jewish Genealogical Research in the Askenazi World... 31

Rabbi, which cumulated the supreme responsibilities in the religiousfield, appeared and consolidated in Poland, Lithuania and the Czechlands, later occurring in Transylvania (where it lasted until 1879) andin Hungary. The religious communities organised themselves intodistrict councils and Councils within Poland and Lithuania, whichlasted until the middle of the 18th century. Similar attempts atcrystallising autonomous supra-community structures were lesssuccessful in the Czech lands and in Germany because of lessfavourable official attitudes there than in the Polish-LithuanianCommonwealth.

In Moldavia and Wallachia, the institution of the chacham provided

the supreme lay and religious authority over the local communitiesled by elected heads from the two provinces, an organisationalsystem that lasted until the temporary Russian occupation between1830 and 1834. In Transylvania, only one community was officiallyacknowledged until 1848 the community of Alba Iulia which wasplaced under the authority of the Chief Rabbi or the National Rabbi ofthe Province. In Hungary and Transylvania, the massivedemographic growth and the gradual development of the legalframework towards civil emancipation led, in the first half of the 19thcentury, to a significant institutional proliferation through theemergence of numerous local communities having rabbis,

synagogues, elected lay leadership, diverse and multiple education,charity and religious structures. The civil emancipation in 1867brought about a tendency for institutional reorganisation in the senseof centralisation; however, the effect of the centralisation decisionsadopted in this respect by the Congress of the Hungarian andTransylvanian Jews in 18681869 had the opposite effect. Thecommunities that accepted the Congresss decisions (the so -calledneologs), those that categorically rejected them in the name ofpreserving community tradition and unaltered autonomy (theorthodox), and those that opted for maintaining the status-quo-anteexisting before this schism, all formed their own structures,

independent from one another and unsubordinated to any central layor religious institution.

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

32/337

32 Ladislau Gymnt

This system was maintained despite all 20th century vicissitudesand tragedies, until the levelling force of the communist dictatorshipimposed a forced re-structuring of the single community model1.

Such were the evolutions from this point of view in Romania,where in the second half of the 19th century the state declined anyofficial acknowledgement of the Jewish religious communities, sothat even though they did not disappear, they nevertheless had tofunction outside a legally-constituted framework. Only after WorldWar I, in the context of civil equality expressed in the 1923Constitution, and the Law of the Cults, adopted several years later,was the de jure existence of the Jewish religious communities

acknowledged in Romania, establishing the principle of a singlecommunity in every town or village, with the exception of the right ofthe Orthodox and Sephardic communities in Transylvania to havetheir own communities. After World War II, a Federation of theJewish Communities in Romania took over the leading role in theinstitutional field, and a Chief Rabbi of the Mosaic cult held supremeauthority in religious matters2.

As far as the evolution of the juridical statute of the Jews in theresearched area is concerned, ever since the first centuries of thesecond millennium, this was regulated through a specific legislationand through privilege acts, given around 12501260 by the kings of

Hungary, Bohemia and Moravia and the Austrian princes, throughwhich the freedom of the Jewish economic activities, the personaland material safety and the free, undisturbed practice of religion weregranted. The fall of some of these kingdoms (especially Hungaryafter 1526), as well as the growing intolerance of the Holy RomanEmpire, resulted in a concentration of Jewish life in Poland andLithuania between the 16th and 18th centuries, where a relatively

1Antony Polonsky, Jakub Basista, Andrzej Lihle-Lenczowski, The Jews in Old

Poland, London-New-York, 1993; Sources and Testimonies on the Jews in Romania, I-III/1-2, Bucharest: Hasefer, 1986-1999; Rafael Patai, The Jews of Hungary, Detroit,1996; Moshe Carmilly-Weinberger, The History of the Jews of Transylvania (1623-1944), Bucharest, 1994 (in Romanian), Budapest, 1995 (in Hungarian), Jerusalem,2003 (in Hebrew); Ladislau Gymnt, The Jews of Transylvania. A Historical Destiny,Cluj-Napoca, 2004.

2Carol Iancu, Jews in Romania 1866-1919; From Exclusion to Emancipation,

Boulder: Columbia University Press, 1996; Idem, Les Juifs en Roumanie (1919-1938).De lmancipation la marginalisation, Paris-London, 1996.

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

33/337

The Perspectives of the Jewish Genealogical Research in the Askenazi World... 33

trouble-free cooperation between the royal authority and theautonomous Jewish institutional structures was achieved, whichguaranteed, in exchange for the fulfilling of fiscal duties, a favourableenvironment for carrying out a flourishing economic activity. In theautonomous principality of Transylvania, under Turkish sovereigntyduring the 16th and 17th centuries, and later on, in the AustrianEmpire after 1699, a privilege given in 1623 by Prince GabrielBethlen and subsequently reconfirmed numerous times, states withrelative precision the rights of the Jewish population and the limitswithin which these could be exercised, the most important restrictionbeing the limitation of the right to legal settlement to just one town

Alba Iulia. In Moldavia and Wallachia, the statute of the Jews until thedawn on the 19th century was characterised by the phrase hostiletolerance, specific to the GreekOriental world of Byzantine origin:effective freedom for the economic activities, free exercise of religion,all within an environment marked by mentalities hostile towardsalterity, which did not exclude the appearance, in the 18th century, ofritual killing accusations and the break-out of sporadic episodes ofanti-Jewish violence.1

At the end of the 18th century, the practise of enlightenedmonarchs, inspired by Enlightenment philosophy, having asprototype the tolerance edicts of the Austrian Emperor Joseph II,

inaugurated the era of major changes towards integrating the Jewsinto the society of the time as citizens having equal rights, peoplewho consciously assumed the obligation deriving from such statutes.The conditioning of these transformations through the abandonmentof important markers of spiritual tradition and communal autonomyresulted in the following: a profound identity crisis in the Jewishworld; the Haskalah movement and the reform that began inGermany and gathered significant supporters (such as the chief-rabbiAaron Chorin in Arad, a personality who paved the way in thisrespect);2 and the powerful opposition on the part ofChassidism thatwas primarily present in Poland, Ukraine, Moldavia, Bukovina, and

northern Hungary and Transylvania. The severe political

1Ben-Sasson, op. cit., pp. 670-690; Carmilly, op. cit.;Sources and Testimonies..., I-II.

2Moshe Carmilly-Weinberger, "The Jewish Reform Movement in Transylvania and

Banat: Rabbi Aaron Chorin", in Studia Judaica, V, Cluj-Napoca, 1996,pp. 13-60.

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

34/337

34 Ladislau Gymnt

confrontations regarding the civil emancipation of the Jews in the firsthalf of the 19th century culminated in the dramatic period of the18481849 revolutions, which beyond the great expectations ofliberal solutions that remained unfulfilled, highlighted the verydangerous potentiality of prejudices and hostilities against the Jews,foreshadowing the emergence of the modern anti-Semitism thatgenerated the tragedies of the 20th century. Nevertheless, by around1870, the civil emancipation of the Jews became a legallyacknowledged reality in Germany, Hungary, Austria, Transylvania,and the Czech lands, opening the way for a rapid and significantintegration and affirmation of the Jews in the social, economic,

cultural and political life of the respective nations and provinces.

1

Theexceptions to this paradigmatic evolution are represented by Russia(which includes prior World War I a significant part of Poland, theBaltic Countries, Ukraine, Byelorussia, and Bessarabia, which weremassively populated with Ashkenazi Jews) as well as Romania.

In the Russian Empire, the feeble reforming attempts at the end ofthe 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century made way,during the reign of Nicholas I, for the most oppressive regime thatopenly promoted the conversion and the forced Russification of theJewish population. A short period of openness towards liberalreforms, between 1860 and 1880, marked by the reign of the Czar

Alexander II, was replaced after his unfortunate assassination in aterrorist plot by some decades in which the overt anti-Semitism of theofficialdom institutionalised pogroms, numerous clausus laws, andexclusion as common tools of state policy towards the Jews untilWorld War I. The Russian revolution in 1917 finally brought the legal,constitutional acknowledgement of the equality of rights for theRussian Jews, but the Civil War in the following years brought aboutmass violence of indescribable proportions, especially in Ukraine.The communist regime, in its Stalinist and post-Stalinist versions, didnot exclude, despite appearances, the perpetuation and the periodic

1Jacob Katz, Tradition and Crisis. Jewish Society at the End of the Middle Ages,

New-York, 1993; Michael A. Meyer, Response to Modernity. A History of the ReformMovement in Judaism, Detroit: Wayne University Press, 1988; Ladislau Gymnt, TheJews of Transylvania in the Age of Emancipation (1790-1867), Bucharest, 2000.

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

35/337

The Perspectives of the Jewish Genealogical Research in the Askenazi World... 35

outbreaks of anti-Semitism deeply rooted in the mentality of thehighly prejudiced and ignorant majority.1

In the Romanian principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, thegenerous and liberal-inspired goals of the 1848 revolution and of thefirst years after the 1859 unification of provinces soon made way(starting with the 1866 Constitution) for an increasingly restrictivepolicy, sprung primarily from the emerging Romanian middle classsfearof the competition provided by their Jewish counterparts, whowere well-represented, especially in the commercial, industrial andfinancial life of the Moldavian towns. The recognition of Romanianstate independence after the 18771878 war against the Ottoman

Empire was conditioned by the Great Powers on the granting of civilrights for all the citizens of Romania, regardless of confession. Therewas bitter opposition of the Romanian political class and publicopinion against this condition, which successfully prevented until theend of World War I the materialisation of the Jewish emancipationgoals. Only after the adopting of the Minorities Statute, imposed bythe Peace Conference in Versailles in 19191920, and the 1923Constitution of Greater Romania (which included Transylvania,Bessarabia and Bukovina), were the Romanian Jews granted equalcivil rights.2

Civil emancipation was not a universal remedy for the Jewish

problem either in Western Europe (as the Dreyfus Case eloquentlyshows), or least of all in Central and Eastern Europe, where theinterwar period, despite the constitutional and internationalguarantees, marked the unfortunate rise of anti-Semitism, whichultimately turned into state policy in Germany after 1933, an examplethat was followed by Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and from1938, Romania. The effects of this evolution materialised in thetragedy of the Holocaust, through which a large proportion of theJewish population in Central and Eastern Europe was exterminated.The rebuilding of Jewish life in the post-war period was marked by

1 John Doyle Klier, Imperial Russias Jewish Question 1855-1881, CambridgeUniversity Press, 1995; S.M. Dubnow, History of the Jews in Russia and Poland,Teaneck NJ: Avotaynu, 2000; Yelena Luckert, Soviet Jewish History 1917-1991: An

Annotated Bibliography, New-York: Garland, 1992.2

Carol Iancu, Jews in Romania...; Idem, Les Juifs...; Beate Welter, Die Judenpolitikder rumnischen Regierung 1866-1888, Frankfurt am Main-Bern-New-York-Paris,1989.

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

36/337

36 Ladislau Gymnt

the new communist dictatorship, whose initial egalitarian andinternationalist promises were drastically disproved by a politicalpractice in which anti-Semitism, exclusion and discrimination weremore or less overt. The result was a constant decrease in thedemographic extent of the Jewish population through emigration toIsrael and to the West, an instrumentalisation of the communitypractices by the dictatorial regimes, which had visible repercussionsat the level of Jewish family life and history. The fall of communism in1989 opened up the possibility of an institutional and spiritualrenewal of Jewish life in Central and Eastern Europe, albeit notwithout the persistence of some flaws from the past which, felt to this

day, have left their mark even on the possibilities of research in thefield of Jewish genealogy.

*

Making reference below to the fundamental sources of suchresearch, it has its origin in the policy adopted, beginning with the18th century, under the influence of a mercantile economic doctrine,by the states in our area of interest regarding the statistical recordingof the population and its material resources with a view to adequatelyknowing the basis for taxation and recruitment. These censuses and

general levies also recorded the Jewish population, and as itsintegration in society became an objective of state policy, specialstatistical records regarding this segment of population highlight thenumber, the geographic origin, the family and professional structure,the territorial spread and the resources that could be subject totaxation. In Transylvania, for instance, the first such population levyof the Jewish population was done in 1753, and in Moldavia, a levy ofthe 1,400 Jewish families was done for the first time by the Russianoccupying authorities during the Russo-Turkish war in 17681774.1After the integration of some provinces having a numerous Jewishpopulation in the Austrian Empire, Russia and Prussia, following the

three partitions of Poland and after the territorial amputation ofMoldavia, the massive growth of the Jewish population and itsmigrations within the great empires mentioned above led to the

1L. Gymnt, The Jews of Transylvania. A Historical Destiny, pp. 161-162; Sources

and Testimonies..., II/2, pp. 104-132.

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

37/337

The Perspectives of the Jewish Genealogical Research in the Askenazi World... 37

expansion of the statistical recording practice at the general,provincial and local levels to the level of the families, as the systemof official records containing births, marriages and death wereintroduced. In the Austrian Empire, the first official measures in thisrespect date back to the end of the 18th century, being initiated bythe reformist monarch Joseph II.The task of recording the data fell onthe clergy of each confession (in our case, on the rabbis). Thesources preserved in the archives prove an uneven application ofthese regulations, even though rabbinical records emerged at theend of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century. InTransylvania and Hungary, for instance, such sources from Arad

date back to 1794, and in Bukovina, sources from Suceava go backto 1843. In Prussia (including the Polish parts of the former kingdom),the system of rabbinical records became generalised after the greatmodernising reforms following the countrys defeat before NapoleonsFrance in 1806. Napoleon is also responsible for the introduction, in1809, of the registry records, common for all inhabitants, in theGrand Duchy of Warsaw; in 1826, the Czarist occupation regimeinstated the system of rabbinical records in the part of Poland subjectto Russian authority, as well as in Ukraine, Byelorussia, the BalticCountries and Bessarabia. In Moldavia, traces of such recording ofvital events by the rabbis were preserved from the seventh decade of

the 19th century in Botoani and Flticeni.A new phase in the evolution and modernisation of the recordingsystem was represented by the introduction of the official registries,with single records for all the inhabitants, regardless of theirconfession, kept in the official registry of the state administration.This system was inaugurated beginning in 1865 in Romania, after theunification of the Moldavian and Wallachia principalities; in 1874 inthe newly unified German state; and in 1895 in the Hungarian part(including Transylvania) of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which wasformed in 1867. The Austrian part adopted the registry system only in1938. The rabbinical recording of the vital events continued in

parallel with the state registry, as far as the births, the religiousmarriages and the burials in the Jewish cemeteries were concerned.1

1For all the data regarding the introduction of the rabbinical and state records in the

different countries of the region, see: Sallyann Amdur Sack, Gary Mokotoff, op.cit.

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

38/337

38 Ladislau Gymnt

Taking into consideration the accessibility of the sources forresearching the Jewish genealogy, the official regulations presenting local differences stemming from the politics or mentalitiesspecific to each country in the above-mentioned area generallyconverge towards the permission for researching the registry recordsolder than one hundred years, usually kept in the departments,directions or regional offices of the national state archives. For thestate records of the last hundred years, which are kept in theadministrative registry offices, the access by citizens is limited orforbidden by the different legal practices motivated by the potentialimplications on the rights of the people who are still alive. The

archives of the Jewish communities, the burial records and thecemeteries are generally accessible to researchers, sometimes inexchange for paying a fee, but their state of preservation is largelyinfluenced by the enormous destruction that occurred during theHolocaust.

Taking into consideration these historical antecedents and presentconditionings, we would like, in the end, to propose some possibledirections regarding the orientation of the future research in Jewishgenealogy in the Ashkenazi world in Central and Eastern Europe:

1. Indexing the available sources for each country.

From this point of view, one can find remarkable achievements,thoroughly inventoried in the Avotaynu guide for Jewish genealogy,edited by Sallyann Amdur Sack and Gary Mokotoff in 2004. MiriamWeiners works regarding Poland, Hungary and the Republic ofMoldova (Bessarabia), that of Gyrgy Haraszti regarding Hungary orJane Sarmanyovas work for Slovakia can be considered as models1.Romania is the country most solicited from the point of view of theintentions for researching the history of Jewish families, but heresuch an essential work tool is still missing. Making up a directory ofthe rabbinical and state registry records, and of the other archivalsources relevant for Jewish genealogy, would be an invaluable

project. As is the case of the quoted bibliographical antecedents, the

1Miriam Weiner, Jewish Roots in Poland, New-York-Secaucus, NJ, 1997; Idem,

Jewish Roots in Ukraine and Moldova, New-York-Secaucus, NJ, 1999; HarasztiGyrgy, Hungarian-Jewish Archival Repertory (in Hungarian), I-II, Budapest, 1993;Jana Sarmanyova, Slovak Parish Registers for the 16th-19th Centuries (in Slovakian),Bratislava, 1991.

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

39/337

The Perspectives of the Jewish Genealogical Research in the Askenazi World... 39

cooperation with the national archives and registry offices would beessential, although their reticence to such an endeavour has so farbeen obvious. The project is doable, involving a group of youngresearchers, PhD candidates and students who, under competentsupervision, could gather the material for the directory within one ortwo years. Its publication under the aegis of the International Institutefor Jewish Genealogy would be a remarkable step forward in thedevelopment of the historical studies of the Jewish families in Centraland Eastern Europe.

2. Indexing the publishing of the official statistical records.

These sources (censuses, levies) are essential primarily for theperiods when there were no rabbinical or state records, as well as forcompleting, verifying and correcting the data in the existing records.Premises and models exist from this point of view as well, such as inthe case of Romania the uploading onto the Internet of the 1942censuses of the Romanian Jews referring to the males born at theend of the 19th century, done by a team of ROM SIG andJewishGen, or the publication in a printed form of the 18241825census of the Jews in the Moldavian capital, Jassy, who were underthe protection of foreign consulates.1 The systematic gathering ofdata regarding these sources and the electronic printed publication of

the information they contain would be a long-term project of greatperspective and usefulness.

3. Indexing and processing the information provided by thefuneral inscriptions in the Jewish cemeteries.

In this case as well, a first stage, largely achieved through theproject of the International Association of Jewish GenealogySocieties and the important contribution of the United StatesCommission for preserving the American heritage abroad, includesan inventory and levy of the existing cemeteries. The next step wouldbe to trace and index the burial records in the community archives

and in the Chevra Kadisha funds, so that the funeral inscriptions inthe cemeteries could subsequently be exploited. In the case of

1Ioan Caprou, Mihai-Rzvan Ungureanu, Statistical Records Concerning the City of

Iai(in Romanian), II, Iai, 1997.

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

40/337

40 Ladislau Gymnt

Romania, a pioneering work in this field, having a model value, hasbeen drafted for the more ancient part of the great cemetery in Siret1.

4. Gathering genealogical information from the manuscript noteson the Hebrew books or on books making reference to Jews writtenin other languages.

A recent doctoral thesis defended in Cluj and dealing with theHebrew book reserve of the Satu Mare community, including some400 volumes,2 highlighted the promising potential existing in themargin notes made by the book owners or readers for tracing originalinformation on family history. A systematic research of the

community book funds or of those in the great libraries and theexploitation of the already published notes would provide a highlyinteresting source through the evident surplus of information and thecomplementary nature of the data in relation to the other availablesources.

5. Creating databases and publishing the list of Jewish studentsin the universities of the countries in the researched area, indexingthe processing of the school documents and records3.

6. Indexing the data referring to the Jewish soldiers, publishing

some lists containing the numbers of the dead, the wounded and thedecorated soldiers in the wars they took part in4.

7. Creating a database to include the dates of vital events andthe names, the residences and the professions of the peopleidentified through the research carried out.

1Silviu Sanie, Everlasting Stones: The Monuments of the Jewish Medieval Cemetery

from Siret (in Romanian), Bucharest: Hasefer, 2000.2

Maria Radosav, Jewish Books and Printing in Northern Transylvania in the 18th-19th Centuries. Doctoral thesis coordinated by Prof. Moshe Idel and Prof. Ladislau

Gymnt, defended in Cluj-Napoca, at Babe-Bolyai University, on August 24, 2006.3

See, for instance: Iancu Braustein, The Jews in the First Romanian University 1860-1948(in Romanian), Iai, 2001.

4 See, for instance: Dumitru Hncu, Lya Benjamin, Constantin Antip, The Jews of

Romania in the War for the Reunification of Romania 1916-1919 (in Romanian),Bucharest, Hasefer, 1996.

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

41/337

The Perspectives of the Jewish Genealogical Research in the Askenazi World... 41

Such a built up and updated source would form an extremelyuseful starting point for future projects and, at the same time, wouldenable one to avoid the repetition of some research initiatives thathave already been carried out.

Therefore, one can find multiple and extremely promisingdirections for the development of the Jewish genealogy studies andresearch in the Ashkenazi area of Central and Eastern Europe in theyears to come. The establishment of the International Institute forJewish Genealogy in Jerusalem undoubtedly marks a turning point ofuncontested value for the materialisation of as many of the above-mentioned possibilities within a foreseeable timeframe.

We wish it every success in this important mission.

Rezumat

Succesul cercetrilor de genealogie evreiasc este condiionat decel puin trei factori: cunoaterea aprofundata mediului istoricgeneral i local; elucidarea evoluiei sistemelor de nregistrare aevenimentelor vitale (nateri, cstorii, decese); clarificarealocalizrii, strii de prezervare i a accesului la sursele arhivistice ide alt natur disponibile cercetrii. Direcii posibile privind

orientarea cercetrii viitoare de genealogie evreiasc referitoare lalumea achenaz din aria central- i est-european ar fi:repertorizarea surselor disponibile din fiecare ar; repertorizarea ipublicarea nregistrrilor statistice oficiale; repertorizarea iprelucrarea informaiei furnizate de inscripiile funerare din cimitireleevreieti; adunarea informaiei genealogice din nsemnrilemanuscrise de pe crile ebraice sau de referin evreiasc n altelimbi; constituirea unei baze de date care s includ nume, dateleevenimentelor vitale, reedina, profesia persoanelor, toate acestedate rezultatnddin cercetri efectuate.

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

42/337

INTEGRARE I RESPINGERE.CAZUL DUBLEI IDENTITI LA EVREII DIN ROMNIA

Lya Benjamin

Teza demersului nostru este c n epoca post-emancipaionist,dubla identitate la evrei a devenit o realitate cultural i civic.Sintagmele evreu german, evreu maghiar, evreu francez, evreuromn nu reprezint deloc delimitri geografice, ci au un coninutidentitar. Evreii din diaspor au dovedit o capacitate unic de

aculturaie, de integrare cultural-spiritual n societile rilor n careau trit, pstrndu-i, ns, contiina apartenenei la evreitate. Unadin expresiile eseniale ale procesului integraionist este nsuirea dectre evrei a limbii rii n care triesc: nu doar ca limb decomunicare cu cei din jur, ci ca limb matern i de creaie. Dupunele aprecieri, acest fapt reprezint cea mai nalt expresie deintimizare cu spiritualitatea mediului nconjurtor. Este vorba despreun curent cultural n contextul diasporei, fundamentat de evreulgerman, filozoful Moses Mendelssohn, n a doua jumtate a secoluluial 18-lea. Ca exponent al Iluminismului, el vedea n nsuirea limbiigermane de ctre evreii din Germania (n Bildung und Kultur) o

soluie pentru problema evreiasc artificial creat de-a lungultimpului de ctre antisemitismul european. Acest curent a cptatextindere i la evreii din Romnia, mai ales din a doua jumtate asecolului al 19-lea. Exponenii evrei ai micrii iluministe elaboreazun adevrat program de aculturaie prin nfiinarea de coli israelito -romne, prin publicarea de ziare i reviste n limba romn, dar nconinut cu problematic specific iudaic, prin constituirea desocieti culturale i filantropice cu titluri de inspiraie iudaic (Zion,Sinai .a.), dar cu statute i programe de activitate scrise n limbaromn sau bilingve. Rezultatul acestui proces a fost, printre altele, oadevrat explozie de talente care au creat valori n limba romn n

domenii precum literele, filozofia, tiinele sociale, tiinele naturale.a.

Este de remarcat c fenomenul dublei identiti, dei nedefinitconceptual, i-a preocupat n coninutul su pe diveri gnditori evreidin Romnia, printre care pe filozoful I. Brucr, pe rabinul-filozof I.I.

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

43/337

Integrare i respingere. Cazul dublei identiti la evreii din Romnia 43

Niemirower, pe etnologul, istoricul i publicistul M. Schwarzfeld i, nun ultimul rnd, pe scriitorul Mihail Sebastian.

Filozoful I. Brucr scrie despre dubla naionalitate a evreilor,subliniind faptul c, dei evreii s-au integrat n colectivitile naionalecu care convieuiesc, acest lucru nu nsemneaz c s-au dezis deevreitatea lor. n acest sens, Brucr conchide: Un Spinoza, Heine,Herman Cohen, Bergson, Antokolsky pe care mintea noastr iconsider ca dezlipii definitiv de la evrei fiindc au fost buni germani,francezi sau rui, au rmas totui, nacelai timp i evrei, realiznd,astfel, i ei fenomenul de dubl naionalitate1.

Asimilismul total s-a petrecut la scar individual. Evreii au fost i

au rmas o naiune pentru care religia i naionalitatea sunt intimlegate. Ceea ce nu i-a mpiedicat ns s manifeste devotament ifidelitate fa de ara adoptiv n care s-au integrat n epoca post-emancipaionist; este o realitate istoric ce a introdus un element dediversitate n unitatea naional evreiasc.

Niciodat iudaismul nu a fost rzleit n att de multe grupuri ca nprezent2, scria I.I. Niemirower la nceputul secolului 20. Ct timpevreii n-au luat parte la civilizaia general, ei s-au desprit unul dealtul numai prin gradul culturii i foarte rar prin calitate. Astzi ns conchide tot Niemirowercnd i noi lum parte la cultura statelorcrora aparinem i a popoarelor n mijlocul crora trim, diferim prin

limbile pe care le vorbim i interesele de stat ce le avem3

.n privina limbii pe care o vorbesc evreii europeni, Niemirower

disociaz limba istorico-ebraic, dialectele-jargon i cel puin aselimbi europene n care gndesc i creaz sute de mii de evreieuropeni.

Dar, cu toat aceast difereniere, au rmas anumite nvturi aleiudaismului i particulariti ale neamului evreiesc comune tuturorgrupurilor de evrei sus-menionate. Particularitatea unei etnii nupoate fi totui anihilat de cultura i spiritualitatea ncorporat nprocesul aculturaiei. Rmne un mod de gndire i simire n strilecontiinei i ale subcontientului formate n fraged copilrie sub

1I. Brucr, Dubla Naionalitate, n Lumea Evree, an I, nr. 2, 2 februarie 1919,

pp. 1 3.2 Dr. Iacob Ihac Niemirower, O academie iavneian modern, n I.I.

Niemirower, Iudaismul, Bucureti, Editura Hasefer, 2005, p. 277.3Loc. cit.

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

44/337

44 Lya Benjamin

influena educaiei, a tradiiei religioase i laice. Dar, mai presus deorice, mai ales n cazul evreilor, un factor definitoriu n meninereaunitii evreieti este comunitatea de destin (Schiksalsgemeinschaft,dup expresia lui Otto Bauer).

Din aceast mbinare original a culturilor i tradiiilor s-a creat,printre altele, o literatur evreiasc exprimat n limba romn sau nalte limbi vorbite de evrei n diaspor. n cazul Romniei, Niemirowerse refer la cele 19 volume ale Anuarului pentru israelii (aprutentre anii 1877 i 1899), la memoriile dr. Adolf Stern n care, cumspune rabinul filozof, sunt zugrvite luptele evreilor din Romnia cuei nii i cu mediul n momentul ieirii din ghetou i al intrrii n

citadela romneasc

1

. Este relevant i dramaturgia lui Ronetti-Roman, lirica lui Steuerman, ntreaga pres evreiasc interbelic .a.O privire istoric asupra devenirii dublei identiti a evreimii n

contextul romnesc dovedete printre alii Moses Schwarzfeld carescria: Datinile, credinele i obiceiurile se consider ca linie dedemarcaie ntre neam i neam. Dar orict de mult ar diferi ntre ele,mpreun vieuiesc, contactul zilnic terge ncetul cu ncetuldeosebirile i opereaz o desvrit apropiere. Cine ar putea safirme dac evreii de azi sunt la fel ca evreii de ieri? Numai unul carenu cunoate istoria culturii lor2.

La problematica dublei identiti se refer i M. Sebastian cnd

scrie despre faptul c n faa valorilor iudaice, se ridic o serie devalori locale, romneti n Romnia, franceze n Frana, germane nGermania. A confrunta aceste dou cicluri paralele de valori conchide ela le gndi, a ncerca s stabileti relaii ntre ele, este,se pare, o obligaie interioar dintre cele mai normale3.

Dar aspiraia lui Sebastian, ca i a altor creatori evrei de limbromn sau de limb german sau de alt limb, de a se implica nfenomenul cultural al rilor respective a fost cu greu acceptat.Iluziile integraioniste nu s-au adeverit, s-au transformat n deziluzii.n optica noastr, analiza fenomenului merit s stea n atenia

1Dr. I.I. Niemirower, Precuvntare", n Iudaismul, p. 226.2

M. Schwarzfeld, Excursiuni critice asupra istoriei evreilor din Romnia, nEvreii din Romnia n texte istoriografice antologie, Bucureti, Editura Hasefer,2004, p. 255.

3 M. Sebastian, Cum am devenit huligan, n De dou mii de ani, Bucureti,

Editura Hasefer, 1995, p.252.

-

7/22/2019 No i Perspective

45/337

Integrare i respingere. Cazul dublei identiti la evreii din Romnia 45

cercetrii istorice pentru nelegerea destinului de diaspor al evreimiimoderne, a relaiei dintre integrare i respingere respingere care aculminat cu Holocaustul.

Fenomenul respingerii ambiiilor de integrare din partea creatorilorevrei apare nc din a doua jumtate a secolului al 19 -lea. Genezastereotipurilor antisemitismului cultural i are probabil rdcinile nfaimosul eseu antisemit al lui Richard Wagner intitulat DasJudenthum in der Musik1.

n optica lui Wagner nu este necesar s fie demonstratiudaizarea artei moderne cci ea sare n ochi i se dezvluie de lasine. Pentru Wagner, pericolul acestei realiti pentru cultura